The Piano in the Sukkah: Early Twentieth Century Immigrant Jewish Piano Culture in New York

By Sarah Litvin

“The Greenhorn of Plenty: The Piano in Sukkah” cited in Andrew Heinze, Adapting to Abundance, 40.

In 1905, the Yiddish language New York newspaper Yiddishes Tageblatt reported on a new trend in the city’s Lower East Side, “The Greenhorn of Plenty: The Piano in the Sukkah.”[1] Jewish families were hauling parlor pianos to rooftops to incorporate them into the holiday of Sukkoth, the article explained.[2] During this week-long fall harvest festival, families erect temporary “booths” or open-air huts as a way of reenacting and commemorating the experience of the Israelites who wandered in the desert for forty years following their exodus from Egypt. Eastern European Jews would have been accustomed to decorating their Sukkoth with fruits and vegetables. In New York City, the community integrated the piano, a symbol of the material and cultural abundance of their new home, into their traditions. Yet the adoption of this American status symbol into Eastern European Jewish households and religious frameworks was not so seamless as this article suggested. New York City’s Jewish-American community engaged with the piano both as a symbol of their status and as a tool to explore older and newer social, religious, musical, economic, and gender roles and practices.

New York City’s Jewish immigrant population exploded between 1903 and 1915 when 1,271,676 Jews immigrated to the United States along with 10,520,180 others. At the same time, American piano production increased at a rate of 6.2 times faster than population growth, and prices declined steeply, putting cheap parlor uprights within reach of wage-earners. The peak year of immigration was in 1907 when 1.7 newcomers arrived, and the peak year of piano production was in 1909 when 364,545 pianos were sold. By 1910, more American homes had a piano than a bathtub.[3] No sales records remain to offer statistics of piano purchasing for the immigrant Jewish community, but between 1900 and 1928, more than twenty different local and national piano companies placed Yiddish-language advertisements in Jewish newspapers.[4]

Savvy Lower East Side piano firms employed Jewish religious language as well as American cultural symbols to teach new immigrants that purchasing a piano was key to celebrating holidays in their new home. The number of piano advertisements in the Forward, the largest-circulation Yiddish language daily, swelled significantly in the weeks leading up to Jewish holidays. By 1908, many were offering “Yerlikher Yontov Sale” or “Yearly Holiday Sale” during the autumn High Holiday season. Many of these advertisements built on Jewish practices such as purchasing new clothes to honor the yontov. For example, the company Spectors wrote on September 1, 1914, “We invite all those who are thinking or dreaming for yontov of a new piano in their house to seek out our piano store and to wonder at our new piano stock of high-grade pianos and player-pianos that were purchased in honor of the yontov season.”[5] Other piano firms’ advertisements aimed to show new immigrants that purchasing a piano could help them to “fit in” as Americans. Two 1911 advertisements for Schubert and Goetz pianos in the Yiddishes Tageblatt depicted none other than Santa Claus pushing a piano into a young couple’s home.[6] The caption, “A Piano or Player Piano for Hanukkah,” suggested that Jewish immigrants could try on American culture without forsaking their own traditions--and a piano could help them to strike this balance.

“A Piano or Player Piano for Hanukkah,” Yiddishes Tageblatt, December 14, 1911.

Before 1910, few Eastern European Jewish immigrant New Yorkers would have brought the skills to play the piano from their towns of origin, so newcomers would have also pieced together the instrument’s cultural significance from their observations of its uses on the Lower East Side. Uprights covered in doilies stood proudly in the homes of neighbors and beckoned from store windows, connoting leisure and high status. The Yiddishes Tageblatt wrote: “In a large proportion of the tenements of the East Side . . . pianos are to be seen in the dingy rooms.”[7] And a 1904 Yiddish Daily Forward article announced, “As for children pounding on pianos, it has become a craze. There are pianos in thousands of homes, but it is hard to get a teacher.”[8] Meanwhile, at the theaters, movies, and other sites of leisure, pianos jangled with ethnic, ragtime and popular music played by people just like themselves, who made money from this work. Drawing information from these observations, as well as the newspaper advertisements and settlement house teachers who offered them lessons, newcomers constructed their own, often conflicting, ideas about what purchasing or learning to play the piano would convey about them.

Some Jewish immigrant mothers understood the piano as a way to prepare their daughters for marriage. Elizabeth Stern, who immigrated with her family from Poland to Pittsburgh in 1892, recalled in her memoir that when she turned 13 years old, the traditional age of Jewish womanhood, her mother determined it was time for her to begin piano lessons because “In America, to be a gentlewoman I hear, you must know how to play the piano.”[9] Similarly, Samuel Chotzinoff remembered of his childhood on the Lower East Side, “A plain-looking young lady who played the piano had an edge, in the matrimonial market, over those who didn’t. Piano-playing was noted down as an asset in the shadchen’s [matchmaker’s] little notebooks.”[10]

This choice by Jewish immigrants to invest their time, money and attention in girls’ piano lessons marked an important change in indicators of social status. In Eastern Europe, a young man’s Torah knowledge could elevate his family’s status. But in New York, a 1917 survey reported that only 23.5% of Jewish children who attended public school received any formal religious education.[11] Meanwhile, piano teachers were in hot demand. Joseph Opatoshu published an autobiographical novel of his life as a Hebrew teacher on the Lower East Side in 1919. As the protagonist, Friedkin, waits outside his pupil’s door, he thinks:

“…The piano teacher probably did not have to wait for his pupil…He understood that piano playing occupied a higher rank than Hebrew; therefore the piano teacher was entitled to better treatment than the Hebrew teacher.”[12]

Whether teaching a child to play the piano would enable or encourage him or her to turn away from their religious training was a topic of concern for immigrant parents. “Girl Playing Piano,” a postcard produced by the Hebrew Publishing Company in 1910 to be sent in honor of Rosh Hashonah, uses a female pianist to evoke a religious Jewish-American “lady.”

Ellen Smith, “Greetings from Faith: Early-Twentieth-Century American Jewish New Year Postcards,” in The Visual Culture of American Religions, ed. David Morgan and Sally M. Promey, First Edition edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 229–48.

The card exhibits material wealth as a complement to, rather than a substitute for, religiousness: The beautiful parlor is adorned by a plush couch, carpet, and framed wall paintings, while wine and apples—traditional Jewish New Year foods–-complement the scene. The young pianist epitomizes the ideal of intersecting American and Jewish identities, as she uses an American material item, the piano, to play “Kol Nidre,” the sacred Jewish chant that ushers in Yom Kippur.[13]

By contrast, the 1927 film The Jazz Singer presents the parlor piano as a tool Jewish-American children might use to rebel against their parents and reject their religious traditions. The first talking scene in motion-picture history shows Jack Rabinowitz seated at the piano, playing for his mother and telling her how his career will make her “a lady.” “‘We're gonna move up in the Bronx. A lot of nice green grass up there. And I'm gonna buy you a nice black silk dress…You'll see, Mrs. Friedman, the butcher's wife, she'll be jealous of you.’” Just a moment later, the piano takes center stage as the source of familial break-down. “Stop!” is the last audible word spoken in this groundbreaking scene, when Cantor Rabinowitz returns home to see his wife enjoying Jack playing Ragtime on his piano. As he fumes, the sound disappears and an intertitle demands, “How dare you bring that music into this house?” Shocked, the cantor disowns his son.[14] While advertisers suggested that the piano offered a seamless update to older Jewish traditions, The Jazz Singer shows how it also had the potential tear families apart across generational and religious lines.

Unknown. English: Poster for the Movie The Jazz Singer (1927), Featuring Stars Eugenie Besserer and Al Jolson. Warner Bros. (Original Rights Holder). 1927. Here. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Jazz_Singer_1927_Poster.jpg.

Similarly, though advertisers depicted pianos as symbols of leisure, Jewish immigrants on the East Side also saw the piano as closely connected to hard work. For a typical immigrant family of six living in New York City in 1902, a twenty-five cent piano lesson would have accounted for two percent of their twelve dollar weekly income. This lesson cost the same as the gas bill for the entire week, and nearly half of the family’s daily food budget ($.56).[15] Even with the help of an installment plan (usually $1 a week or $3 a month), a $200-$300 piano would cost nearly 7% of a family’s monthly income. One of the immigrant Jewish community’s most prolific poets, Morris Rosenfeld, published a poem entitled “The Concert” in 1912 that describes a father’s “mountain of worries” resulting from his hard labor as a tailor and the installments he must pay on “a piano for the girl/And a guitar for the boy.” Yet the poet suggests that his sacrifice pays off when he hears his children play at night. The poem ends:

“At night, life comes/Though all is black around;/ The sweet tones hover/And fill the heart./The dad sits, pale;/The children give a concert./ His gaze grows damp, and damper—/He sits and coughs, and listens.”[16]

While some Jewish-American newcomers in New York saw the piano as a reward for their hard-earned money, others used the piano to earn money. Working-class girls on the Lower East Side of New York found work as pianists in the popular music industry as song-pluggers in music stores and nickelodeon performers where they accompanied silent films. Industry pioneer Marcus Loew, for example, recalled hiring “young ladies who lived near the theater” as pianists and cashiers at the theaters he opened on the Lower East Side in 1905.[17]

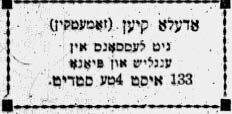

And Jewish-American newcomers who brought piano-playing skills from home monetized them by offering lessons and concerts to neighborhood residents. On New Years Day in 1904, for example, Adela Keane placed an advertisement in the Yiddish Forward offering lessons in “English and Piano” from her home on East Fourth Street.[18]

Joseph Rumshinsky later described his schedule as a piano teacher on the Lower East Side in terms that laid bare the instrument’s role as a tool for work and leisure and a tool to preserve and challenge traditions:

“From ten in the morning until three in the afternoon I taught young women, recently married, who wanted to show their husbands they could play piano. From three until seven I taught school children. And from then until ten or eleven in the evening I taught shop girls and office girls who wanted to get married…”[19]

“Adela Keane (Zametkin),” Jewish Daily Forward, January 1, 1904.

While some teachers on the Lower East Side like Rumshinsky understood their students’ motivations to play and surely shaped their lessons accordingly, other teachers’ own cultural agendas shaped their lessons. Specifically, settlement house workers strove to teach working-class girls to play the piano as a means of cultural uplift, and so focused their lessons on classical music, which they deemed superior to Jewish liturgical or popular music. “Litvishe Khokhma,” or the “Lithuanian-Jewish Smartypants,” a columnist in the Yiddishes Tageblatt newspaper wrote in 1909, “From the hundreds of girls who take lessons for years on the piano—how many of them can go to the piano and amuse! Guess? Very very few!” She went on to tell the story of a fictional girl named “Mary,” who has been diligently practicing her “Bach’s Fugues,” but cannot honor her brothers’ request for a “Cakewalk” or her elderly relatives’ request for “Jewish music” since “her teacher has forbidden her from playing ‘Jewish music’ because this isn’t classical and she’s never practiced it.” The blame for this “calamity” is “fanatical” teachers,’ the author writes since they only teach classical music instead of “all that is popular. Everything people sing in the theater; what men whistle in the streets.” She recommended to parents that they “look upon your piano as a useful art-instrument for everyone and not as a luxury for experts.”[20] Here again the piano served as a tool for Jewish-American families to navigate their cultural adaptation in their new home.

Jewish newcomers to New York in the era of mass immigration and industrial piano production used the piano to construct a new hybrid culture as they settled into the city. Though many purchased a piano as a potent symbol of high cultural status, family members found the parlor piano to be an accessible tool with which to interrogate and integrate older and newer ideas about gender, religion, leisure, and work, and culture. And immigrant Jews in New York weren’t the only ones. My recently completed dissertation, “In Her Own Hands: How Girls and Women Used the Piano to Chart their Futures, Expand Women’s Roles, and Shape Music in America, 1880-1920,” explores how girls and women from different classes, ages, marital statuses, geographic regions, and religious and racial backgrounds similarly employed the piano as a tool to experiment with and reshape gender roles during the years when the upright piano anchored the American parlor.

Sarah Litvin currently works as Director of the Reher Center for Immigrant Culture and History in Kingston, New York. ReherCenter.org. She completed her Ph.D. in U.S. History from the Graduate Center, CUNY in 2019 with a dissertation entitled “In Her Own Hands: How Girls and Women Used the Piano to Chart their Futures, Expand Women’s Roles, and Shape Music in America, 1880-1920. When not writing, she likes to hike, sing, and run. She does not play the piano.

[1] Heinze, Andrew R. Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption, and the Search for American Identity. Columbia University Press, 1992, 40.

[2] Sukkot began this year at sundown on Sunday, October 13th and will end at sundown on Sunday, October 20th.

[3] Craig H. Roell, “The Piano in the American Home,” in The Arts and the American Home, 1890-1930, ed. Jessica H. Foy and Karal Ann Marling, 1st edition (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 85; James Parakilas, Piano Roles: A New History of the Piano (Yale University Press, 2002); Nicholas E. Tawa, A Sound of Strangers: Musical Culture, Acculturation, and the Post-Civil War Ethnic American (Scarecrow Press, 1982), 32.

[4] By the author’s count of advertisements in the September issues of the Yiddish Daily Forward from 1900, 1907, 1914, 1921 and 1928.

[5] Joseph Spector, “Yerlicher Yontov Sale,” Jewish Daily Forward, September 14, 1914.

[6] “A Piano or Player Piano for Hanukkah,” Yiddishes Tageblatt, December 14, 1911.

[7] Moses Rischin, Yiddishes Tageblatt, January 16, 1899, Quoted in The Promised City: New York’s Jews 1870-1914. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977).

[8] “Quoted in Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made,” Jewish Daily Forward, April 1904.

[9] Elizabeth Stern, My Mother and I (New York: Macmillan Company, 1917), 99.

[10] Samuel Chotzinoff, A Lost Paradise: Early Reminiscences, 1st edition (Alfred A. Knopf, 1955), 12.

[11] Annie Polland and Daniel Soyer, Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840-1920 (NYU Press, 2013), 165.

[12] Irving Howe, World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976), 201.

[13] Ellen Smith, “Greetings from Faith: Early-Twentieth-Century American Jewish New Year Postcards,” in The Visual Culture of American Religions, ed. David Morgan and Sally M. Promey, First Edition edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 229–48.

[14] Alan Crosland, The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros., 1927).

[15]“Women of Valor” In Grandma never lived in America : the new journalism of Abraham Cahan. Moses Rischin, ed (Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 1985) 403-404.

[16] Mark Slobin, Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants, 1St Edition edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990), 67–68.

[17] “A Talk With Marcus Loew,” Motography, May 1911.

[18] “Adela Keane (Zametkin),” Jewish Daily Forward, January 1, 1904. Thanks to Dr. Ayelet Brinn for sharing this advertisement.

[19] Slobin, Tenement Songs, 44.

[20] “The ‘Litvishe Khokhme’ Asks Parents Does Your Daughter Take Piano Lessons?,” Yiddish Daily Forward, February 14, 1909, http://jpress.org.il/Olive/APA/NLI/SharedView.Article.aspx?href=YTB%2F1909%2F02%2F14&id=Ar00406&sk=2E40BE6F.