Material Politics of New York: From the Mafia’s Concrete Club to ISIS

By Vyta Baselice

Concrete receives far less attention than cocaine. And it seems for good reason as the two substances are most different: one is a building material while the other is a highly addictive drug; one is legal while the other is not; one materializes environments, like homes, offices, schools, and infrastructure while the other destroys families and communities. It is only in their beginnings as off-white powder that they appear to share any commonality. But what if I told you that politics around the two particles of dust was not especially different? What if I unearthed that concrete — much like cocaine — is embedded in histories of violence, illicit activity, and social and environmental harm?

Enter the New York City Mafia. Few architectural and urban historians have examined the extent to which the organized crime syndicate controlled the construction of the city’s building efforts throughout the twentieth century. Instead, academics have focused on narratives of technological progress that have given life to precedent-setting and record-breaking building efforts, ranging from the Empire State Building to the World Trade Towers, that consumed ever-increasing amounts of construction materials. We have viewed these construction projects largely from above — Berenice Abbott’s documentation of New York’s aggressive construction efforts of the 1930s generated many clammy palms. This post, however, takes the opportunity to understand the city’s construction history from below, digging deep into the politics of building. A historical perspective on construction allows us to better understand the concrete industry today, which continues to embed itself in exploitative behaviors, ranging from labor abuses to environmental harm on American and increasingly foreign soils.

How the Mafia Infiltrated the New York Construction Sector

In 1987, the Mafia Commission Trials finally took down the New York City Mob, which was made up of five notoriously violent families: Gambino, Genovese, Colombo, Lucchese, and Bonanno. The case revealed that while engaging in the typical mafia activities of racketeering, bribery, and murder, the crime syndicate also pursued a new venture — the gargantuan New York City construction sector.

The roots of their investments could be traced back to the early decades of the twentieth century when union and private sector disagreements generated many labor strikes and halted work. The Great Depression likewise weakened the construction sector and left scores of men unemployed. Hungry for projects and guaranteed income, contractors saw the mafia’s infiltration of worker unions as a “necessary evil” since, with a little bribe here and there, they could control strikers and ensure that work got done relatively on schedule.[1] Over time, labor unions and the Teamsters turned a blind eye to racketeering and mafia’s involvement in the New York City construction sector became regular and systematic. Indeed, they even formed the Concrete Club, an organization that regulated the distribution of cement and concrete, ensured workplace peace, and made available workers for projects worth $2 million and over; they also extorted club “dues” and a 2 percent cut of the value of contracts.

In addition to infiltrating the construction sector, the Concrete Club monopolized the ready-mix concrete business in New York City. Unlike cement that was sold in bags and thus required significant preparation before application, ready-mix businesses did the hard work for their customers — they mixed cement with water, sand and desired aggregates, and clients simply dictated where the mixture ought to be poured. The mafia-owned ready-mix businesses supplied the material to multiple projects and ensured that their product would be used regularly and in excess, even when the design did not demand it. With their infiltration of the labor unions and control of the material supply, the Mob had the city in a stronghold. One member articulated this most clearly: “With the unions behind us, we could shut down the city, or the country for that matter if we needed to get our way.”[2] And this was not an exaggeration: by eliminating access to workers and concrete, the mafia could literally stop new and continuing construction of highways, housing, schools, hospitals, and government buildings. Without access to the off-white powder, America could not get its fix of modernity.

In the 1980s, the mafia’s control of construction efforts in New York City became especially evident as the sector expanded and generated around $10 billion of public and private contracts annually.[3] Some contractors, like Stanley Sternchos, had to pay the Mob over $800,000 to keep his projects on schedule as much as possible.[4] In light of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential election, journalists queried to what extent the president-elect collaborated with the Concrete Club when building his hotels during this time period. They found that when constructing Trump Tower, for example, he used a more costly and cumbersome construction method that relied heavily on ready-mix concrete, supplied by the Mob. Not all builders collaborated with the Concrete Club — major New York City developers like LeFrak and Resnick families worked with the FBI and other government authorities to end the mafia’s rule.[5] Responses to the mafia were therefore mixed, encompassing both consent and resistance.

The Mafia and Concrete: A Love Story

So, what made the construction sector and concrete in particular so attractive for Mob investments?

Most obviously, the construction process — particularly in New York City — was extraordinarily complex and multifaceted. Both public and private projects necessitated armies of skilled and unskilled workers who waltzed in for different parts of the project: excavating and laying the foundation; constructing the frame and furnishing it with electrical, plumbing and other equipment; working on interiors; and putting the final touches. Each team of workers was hired separately through different sub-contractors who submitted their bids for the project to a third-party negotiating organization. The convoluted process was difficult to regulate and manage, and it thus created fertile grounds for abuse.

Public construction projects carried with them even further complications. This was in large part due to the federal government’s efforts to make contract bidding a more egalitarian process by dividing projects worth over $50,000 into at least four separate contracts. Such regulations complicated supervision and increased expenses; they also diluted the power of government officials. In time, public sector workers turned a blind eye to the mafia’s involvement. Eventually, they not only ignored Mob activity, but supported it by signing off on construction projects that did not meet the building codes, pushed through paperwork that did not receive appropriate reviews and approvals, and allowed the use of sub-par or even watered down materials. The actions of corrupt government workers seriously jeopardized worker safety and the final building output. One can only imagine how many of New York City’s buildings are weaker as a result of these clandestine and illicit dealings.[6]

And it was not only the Mob that was engaging in unlawful activities — workers regularly stole materials like metal wiring or pipes from the work site to make an additional buck on the side. This behavior was so common and systematic in the industry, it acquired a name, mungo.[7] Contractors too engaged in efforts to improve their profits by relying on cash payroll and failing to pay appropriate federal and state taxes. By attempting to cut corners and find shortcuts, contractors contributed to decreasing public funds to build projects like roads, schools, libraries, and public housing.

Despite the corruption of government workers, contractors, and laborers, the Concrete Club’s greatest power was one it shared with the drug cartel — time. While a delay in concrete delivery did not directly result in death, it did generate extensive financial loss and derailed or entirely stopped many a construction project. In a congested city like New York, every part of a large building effort had to run smoothly and in concert; even a 15-minute delay in truck departure could result in extremely late product delivery and thus hours of missed work and progress. The Concrete Club was ready to flex its hard muscles if contractors failed to pay their dues.

How about Now?

The government’s showdown with the Concrete Club was dramatic, famously involving the FBI and then-US Attorney Rudolph Giuliani. It was both a combination of federal agencies’ smarts and the backwardness of the mafia that contributed to the fall of the Club(indeed, by the 1980s, illicit business tactics had become significantly more sophisticated and rooted in the immaterial realm of finance; the Mob’s practices of bribery, racketeering, and murder prevented them from properly adapting to the new standard). The jury convicted the defendants of all 17 racketeering acts and 20 related charges of extortion, labor payoffs, and loan-sharking. The leaders of the Concrete Club were sent to live out the rest of their lives in prison.

Today much has changed in New York City’s construction landscape. Obviously, the mafia is no longer around to manage the business, and competition and regulation are likewise improved. And while on the surface, the concrete industry shed its illicit dealings, in many ways it merely migrated them to another part of the world where regulation is weak or nonexistent, much like it had been in New York City half a century earlier.

Between 2011 and 2015, as ISIS was ravaging through the Middle East, murdering entire villages and taking people captive as dispensable warriors or sex slaves, the French cement company Lafarge was experiencing a business boom. Its manufacture of cement in Jalabiya, Syria was running smoothly, without the typical environmental and labor hurdles experienced in the West. In order to ensure that cement continued to flow from Syria to other nations without disruption, Lafarge had to preserve access to resources like electricity and fuel, and ensure peace in the perimeter of the cement plant. Paying off ISIS was the only way to accomplish this. And Lafarge paid millions to keep the terrorist organization and other jihadists at bay. In 2018, the company’s actions were discovered and it was charged by international courts with complicity in crimes against humanity.[8]

The incident sheds light on the future of the construction sector, which has become increasingly global, immaterial, and silent. No longer are mafia bosses managing the physical distribution of ready-mixed concrete across the congested streets of New York; instead, major manufacturers are quietly maintaining open networks in unstable and war-torn regions to ensure that the material keeps flowing undisrupted. The concrete industry’s impetus to constantly find cheaper forms of labor and open manufacturing conditions inevitably lead them to pursue illicit and dangerous activities that put workers and environments in harm’s way. We can only imagine what the next iteration in this dangerous trajectory might be.

Scholars of architecture and urban history, therefore, have a tall task in front of them to examine the business of construction and materials manufacture. They will have to combine approaches of local histories, examining place-specific policies and practices, but also integrate them with global approaches that understand how local dynamics shape and are transformed by global ones. Such methodologies suggest a completely different treatment of heavy materials like concrete, interrogating their presumed lightness over stability and invisibility over conspicuousness.

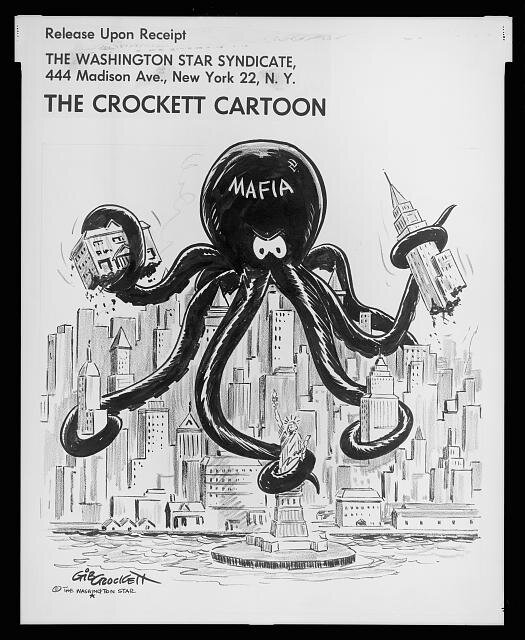

The Mafia Taking Over New York City, Gib Crockett, Washington Star Syndicate, 1967, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-135932

Scene from the Mafia Commission trial, 1987, University of Virginia, Courtroom Sketches of Ida Libby Dengrove, Box 59, folder 329

Guggenheim Museum under construction II, Gottscho-Schleisner, inc., 1957, Library of Congress, LC-G613-71615

Vyta Baselice is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at the George Washington University, where she is completing a dissertation on the cultural and social history of concrete, titled “The Gospel of Concrete: American Infrastructure and Global Power.” Her research is centered on twentieth-century architecture and urbanism, with a particular focus on the manufacture and dissemination of construction materials and their effects upon built, social, and natural environments.

[1] Owen Moritz, “Mob’s Hold Written in Concrete,” Daily News (22 May 1988): 12.

[2] NY State Organized Crime Task Force, Corruption and Racketeering in the New York City Construction Industry: Final Report to Governor M. Cuomo (New York: NYU Press, 1991), 83.

[3] NY State Organized Crime Task Force, Corruption and Racketeering in the New York City Construction Industry, xxiv.

[4] Patrice O’Shaughnessy, “Mob’s Building Bloc: Contractor Says he Paid 800 G in Bribes,” Daily News (17 October 1986).

[5] David Cay Johnston, “Just What Were Donald Trump’s Ties to the Mon?” Politico, 2016, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/05/donald-trump-2016-mob-organized-crime-213910

[6] NY State Organized Crime Task Force, Corruption and Racketeering in the New York City Construction Industry, 137.

[7] NY State Organized Crime Task Force, Corruption and Racketeering in the New York City Construction Industry, 25.

[8] Agence France-Presse, “Lafarge Charged with Complicity in Syria Crimes against Humanity,” The Guardian, June 28, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/28/lafarge-charged-with-complicity-in-syria-crimes-against-humanity