The Dawn of Rapid Transit in NYC: LIRR in the Steam Age

This iconic panorama depicts New York City’s first subway, although you might need a magnifying glass to see it. Just across the East River from the Battery, a puff of smoke plumes a tiny locomotive entering a tunnel from a train depot and ferry house perched on the waterfront. Above the tunnel, the line of tracks sweeps along an avenue to the east, disappearing into the horizon.

That short-lived waterfront tunnel was a harbinger of things to come. The train belonged to the Long Island Railroad Company, which would become America’s busiest passenger line, carrying as many as 118 million people a year into and around New York City. But even as early as 1850, LIRR locomotives had vastly expanded the city’s idea of itself, bringing large areas of rural Brooklyn and Queens within commuting range. Those suburbs would quickly become city neighborhoods.

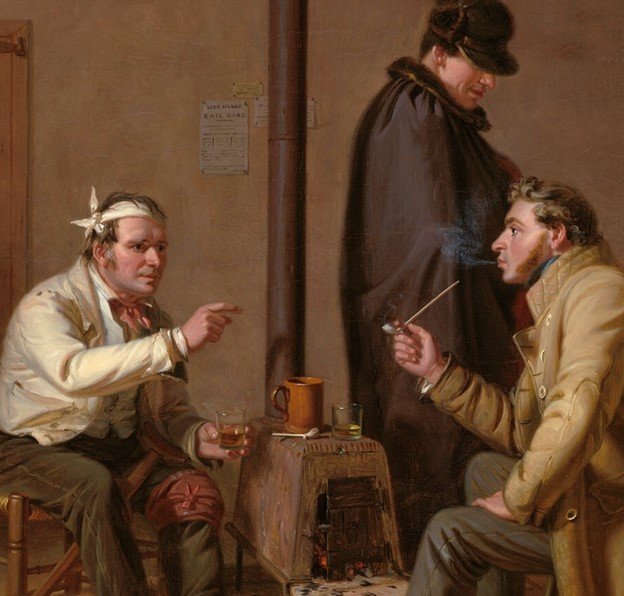

But LIRR steam locomotives were controversial from the start. The first tracks had been laid on the outskirts of Brooklyn, but rapid development soon meant steam trains were running through a bustling downtown. Slow to start, nearly impossible to stop, dirty, loud, and deadly, they were a poor fit for crowded urban districts.

New York’s 1898 consolidation would split Brooklyn and Queens away from the rest of Long Island. Steam was banished from Brooklyn and most of the LIRR’s tracks there were buried underground. Nevertheless, the LIRR was an important provider of mechanized transportation in those two counties, nourishing their booming growth for decades before the arrival of elevated trains or electric trams and streetcars.

Expanding Time, Annihilating Space

Landowners teamed up with Manhattan investors to build the railroad at a time when American cities enjoyed better connections with foreign ports than with each other, and slave-grown cotton was the leading source of export revenue. Connecting the Eastern Seaboard by rail from Charleston, SC, to New England was seen as an economic and political imperative, even a matter of national security. The LIRR was the fastest railroad on the continent, and introduced equally rapid societal changes.

Commuters

“We consider commutation to be the life and soul of railways from large cities,” American Railroad Journal & General Advertiser wrote in 1846. The discounted ticket more than paid for itself by encouraging suburban expansion, with all its spinoff profit in real estate, construction, freight, and travel. Where the LIRR went, residential communities followed, starting in Brooklyn and Queens.

Brooklyn Steam Wars

Decade after decade, Brooklyn simply could not settle what it called “this harassing question” of the place of steam within its borders. In 1833, Brooklyn had formally backed the LIRR‘s charter, citing the advantages it would bring their village. But merchants, landlords, residents, and commuters had sharply differing experiences. Local and regional interests were at odds. The railroad would be restricted, shifted, expelled, brought back, and finally driven underground. Brooklyn’s loss was Queens’s gain.

North Side, South Side: Branching Out

The failure of its express service to Boston left the LIRR dependent on customers at first overwhelmingly concentrated at Long Island’s western end. Denizens of the villages dotting its coves and shorelines were ill-served by a railroad that ran straight up the island’s vacant middle. Only under the existential threat posed by competing railroads did the LIRR begin extending lines north and south.

Another World

In 1900, the LIRR was bought by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which electrified commuter lines, tunneled under the rivers and built its monumental station. Across town, the New York Central was just as busy. The near-simultaneous consolidation of the five boroughs was no coincidence. Only if unified could the city protect citizens from “the organized forces of relentless and absentee capitalism,” civic leaders argued. This would prove the beginning of the end of steam railroads’ dominance in setting the tempo and bounds of life in greater New York.