Retrieved Rhythms: The Last Poets, Harlem, and Black Arts Movement(s)

By Christopher M. Tinson

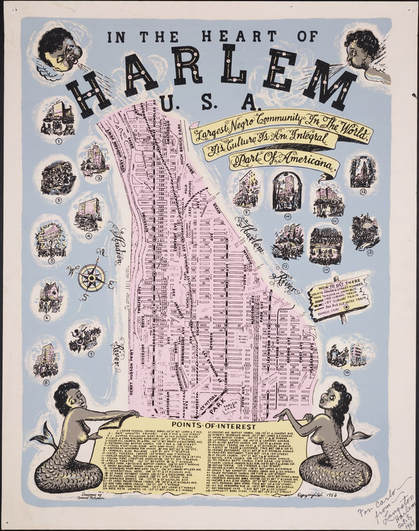

Bernie Robynson, “In The Heart of Harlem,” 1953. Yale Beineke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Used under fair use. https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3520606

In 1953, illustrator Bernie Robynson, in an effort to diagram the culturally diverse and magnetic appeal of Harlem, mapped some of the enchanting points of interest sure to attract wide-eyed tourists. The resulting map entitled “In the Heart of Harlem” calls that section of New York City: “The Largest Negro Community in the World. Its Culture Is An Integral Part of Americana.” Over 12 years later, Harlem’s place in the American imagination would take on a different meaning for its inhabitants of African descent.

Harlem, long known as the mecca of African diasporic people and cultures serves as a critical, enduring, and often ideal setting for the expression of black urban poetics captured beautifully in Herbert Danska and Woodie King Jr.’s film Right On! (1970), which features the dynamic and decidedly vernacular lyricism of The Last Poets. This performance poetry, recently recovered and restored on 35mm film and presented at MoMA in Spring 2013, remains a unique artifact and text through which we might access the Afro-diasporic sensibilities of early 1970s New York City. Moreover, widening our lens in order to locate this film and its subject matter in a greater political and socio-aesthetic context opens up new threads of inquiry into the changing urban landscapes of the city.

From 1970-1976, The Last Poets, whose members comprised various ensembles and collaborations over this period, produced or collaborated on six full-length records. These included self-titled The Last Poets (1970), This is Madness (1971), Black Spirits in collaboration with Amiri Baraka (1972), Chastisement (1973), At Last (1974), and Jazzoetry (1976). Those who have performed under the name The Last Poets have included Gylan Kain, Felipe Luciano, David Nelson, Jalil Nurrudin, Abiodun Oyewole, Sulaiman El-Hadi, and perhaps the most stubborn group member, Harlem itself.

The Last Poets are one of numerous groupings that emerged under the wide umbrella of Black Arts, beginning in 1965 with the formation of the Black Arts Reparatory Theatre and School (barts) in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination, and extending well into the 1970s. This period includes the explosive deteriorating effects of heroine on urban landscapes across the U.S. and the destructive force of the Vietnam War, which, among other signposts of capitalist militarism are forces not unrelated in American history. This history also includes the proliferation of COINTELPRO, urban revolt, the emergence of Black Studies and Ethnic Studies, violent repression of political militancy (see, for example, the Case of the Panther 21), prisoner rebellions, and the expansion of the carceral state in response to political protest throughout the U.S.

The Black Arts Movement mapped radical creativity and aesthetic intensity onto political organizing and theorizing for radical social transformation. This movement, whose most well known architects include Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez, Larry Neal, Haki Madhubuti, and Askia Touré among others, is known as the “sister” to the Black Power Movement (the gendered ordering in the construction notwithstanding), forming one of the most expressive, creative, and robust periods of black cultural production in the 20th century. Mainly situated in the cracked concrete of the inner cities of the United States, it was a movement that rippled and took root and/or identified new routes in other spaces where people of color sought to throw off the trappings of various forms of westernization, colonialism, and racism in search of something in need of self-recovery. That is, the possibility of creating new life out of the chaos of American inner city isolation.

Rod Hernandez, a scholar of literary movements, employs the term “cross-cultural poetics” to call attention to the kinds of radical aesthetic production that Baraka, Sanchez, Don Lee (Haki Madhubuti), Jayne Cortez, Gil Scott Heron, and The Last Poets helped to shape. It was a racialized landscape that included members of vibrant and rich traditions of African as well as Latinx diasporas in the U.S., facilitating what he calls “the blackness of brownness” which made a formation like The Last Poets possible. But this is a collaboration that stretches back to the Afro-Puerto Rican bibliophile, historian, and collector Arturo Schomburg. And to this very day, located at the corner of 136th St. and Malcolm X Blvd. exists one of America’s largest repositories of African and African diasporic cultural and political history, and bears his name.

The radical aesthetic practices shown in the work of The Last Poets as shown in Right On! is demonstrative of a collaborative energy, continuously crafted poetic works in progress, and improvised conversations that were carried from neighborhood tenement, to bodegas, down through subways, to Sunday morning church services and working class hallways, into kitchen table debates, and then back into the streets. As much as any, these were sites of combustible poetic currency, forming a tapestry that linked blackness and Latinidad (embodied mosaics that also rubbed against various practices of Islam, Catholicism, and Christianity) as well as U.S.-based counter cultures while challenging orthodoxies of all kinds. It is no coincidence that the New York Times considered Right On! a “hard-driving evangelical performance.” (Emphasis added). For communities of African descent, this period was as much about how to navigate the shifting contours of white supremacist (or western self-referential) structures and practices, as it was about intra-group, and inter-group identity-formations, alliances, contestations, and quotidian strategies of resilience and resistance.

Though men occupied much of the visual space (as my male-bodied brethren are wont to do), Afro-diasporic women also shaped these landscapes of politicized poetics, self-making, and collective agency. Writers such as Sanchez, Carolyn Rodgers, Gwendolyn Brooks, nikki giovanni, Margaret Burroughs, Cortez, Mari Evans, Valerie Maynard, and Toni Cade Bambara amongst numerous others performed, wrote, debated, produced art, and published as much and sometimes more than their male counterparts. They too published in poetic, theatrical, and other literary forms, could gin-up an audience, and provide keen cultural and political analysis.

Organizations and collectives such as the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords Party, Revolutionary Action Movement, the Nation of Islam, Black Arts Reparatory Theatre and School, Blkartsouth, the Liberation Committee for Africa, the Harlem Writers Guild, On Guard for Freedom, Concept East, Boricua Artists Guild, and New Federal Theatre, and especially independent publications such as Umbra, Negro Digest/Black World, Liberator, Soulbook, Freedomways, and Muhammad Speaks, to name just a few, cultivated numerous politically sophisticated, globally informed, and restless minds in tones black, brown and beige the world over.

Importantly, theatre production was a central element of Black Arts activity and it was perhaps an expected move that Woodie King, founder of the New Federal Theatre in 1970 (which is still in operation today) would collaborate with Danska to produce Right On! In the film viewers are treated to a raw blend of poetry, music, and theatre emerged as pillars of Black Arts Movement modalities. Whether or not these forms can be successfully captured on film is still up for debate, as it seems that poetry on film has receded while even older forms such as musicals are converted into Blockbusters (see the film Chicago, for example) with the financial muscle of Hollywood. In Right On!, however, viewers are ushered into a cinematic frame where Black wor(l)d-smiths utilize voice, throat, backbone, breath and syncopation, to reimagine and create anew an Afri-diasporic sonic landscape. Though emerging from the hustle and flow of the hood under late capitalism, these were old world storytellers, griots, “priest-philosophers”—in Black Arts Movement poet Askia Touré’s words—in New World locales, with a rooftop view of the world, a new day becoming, an imaginary that put the bottom row on top this time. Recall that the song “Go Tell it on the Mountain” may have been popularized in the pews of the black church, but its secular reach is as significant to the black political imagination.

These individuals and collectives were working through a constant invocation of diaspora-memory, carving linguistic possibility out of the movement and migratory necessity of diaspora. They combined history, deification, music, lyric, echo, whisper, chant, and ancestral veneration as a way of mapping diaspora consciousness, as locally rooted and transnational. They routes they charted entailed a long process of writing oneself into history, but also was an act of writing oneself into memory. The notion of transition, like diaspora, helps describes the sense of moving from one place/space to the next often for the sake of survival, for the full expression of humanity embodied and traced in terms that are transnational, transcommunal, and translocal. Restless movement. In this sense, New York City and Harlem (as well as the Harlems of other U.S. cities) represents the behemoth of the metropolis, the landscape of transnational imaginary, and a de-industrial ground zero—both heaven and hell on earth. In the anthology Black Fire, edited by Neal and Baraka, the South African protagonist in Keorapetse “Bra Willie” Kgositsile’s poem “The Awakening” remembers:

Then came I to America

Twentieth century capital of the living dead

It should not surprise that black artists would attack head-on the age-old question of poetic function by demonstrably asserting the artistic necessity to inspire if not incite, to critique, to dismantle and dislodge, to unsettle and update, to unearth and give birth to newness, to knowing, and to uncover and rediscover the knowable. The question of knowledge production—the question of epistemology—would be taken up with force in the formation of Black Studies departments in colleges and universities as a challenge to the orthodoxy of the American academic landscape from 1968 until the present day.

The Black Arts Movement concerned the relation between the artistic and the organizational, not simply between the cultural and the political. It was a radical sense of aesthetics—the search for a distinctively black aesthetic in Larry Neal’s words—that these artists strove towards and embodied. The artistic and the organizational were political projects of strategy and imagination, what might be thought of as the presentation of presence through institution building, and the constant process of self and community (re)making.

Attention to the organizational aspect of this movement emphasizes the collective nature, organic collectivity, vernacular contact, and intra-communal dialog and dialogics that helped foster the talents and volcanic energy of all sorts of musicians, visual artists, and political curators of a black diasporic imaginary. These were places of shared meaning, sites for the circulation of origin stories, narratives of escape, capture, and just-misses hurled into a reservoir of artistic originality within overlapping diasporas of tradition; patterns, traces, and shapes, and the desire to live on ones own terms.

The voices emerging from black bodies and against brick backdrops depicted on screen in Right On! perform a vocalized recasting of their self-possessed bodies as quintessential instruments of daily resistance but offer a vision of black futurity. The Last Poets, and their loose-knit community of poets, deployed a lumpen-language framed in free floating stanzas atop, inside, and through African, Afro-Caribbean, and Black Belt tempo. Indeed, Black Arts offered a new language, which tested the narrow limits and definitions of style, delivery, and grammar. It was at once an affront to a racist literary tradition and establishment definition of high art (or any art for that matter), and the orthodoxy of racial meaning simultaneously. Not about an essential and enduringly stiff notion of blackness as much as about mobilizing a constellation of meanings, a universe of understanding, an “us”-ideology or a “we”-philosophy, what critic and curator Michelle Joan Wilkinson has called a “New World poetics” as an antidote to what scholar Jared Sexton calls “New World antiblackness.”

There is a certain sense of omniscience in being the Last, as in The Last Poets. And in this case a bitter irony to know that Harlem, the character in the film that stays on set long after the cameras had been packed, will only last in memory. That is to say that the Harlem of Afro-diasporic yearning and place-making is being replaced with the “SoHa” of gentrification, where the rooftop is no longer a throne for lumpen-royalty, and the city resembles anything but home. Listen to how one cheerleader of displacement described the transition: Forget SoHo and get used to saying SoHa. Otherwise known as South Harlem, the rapidly changing neighborhood is a spot on the map that more New Yorkers will soon get acquainted with as it continues to transform. In recent years, South Harlem has seen an influx of new housing developments trailed by new businesses, all managing to quickly change the neighborhood into one of the city's newest hubs. It’s dotted with trendy establishments and a diverse population, but it still maintains classic Harlem charm.

While the removal of black people from cities has been a staple of American revitalization projects for nearly five decades, only recently has gentrification reached consistent mainstream concern. As it stands, the 1979 disco hit single by the duo McFadden & Whitehead “Ain’t no stopping us now” might as well be the theme music for the agents of relocation: American real estate developers, speculative investors, realtors, and elected officials. Bernie Robynson’s 50s-era vision be damned! The revolutionary poetics that The Last Poets carried out of the dark past of the present won’t be enough to stop this, no matter the prescience of their voices and those of their fellow critical wordsmiths.

But where did The Last Poets go after Right On!? Felipe Luciano followed the advice of mentor-poet Amiri Baraka and shifted his creative energies into an explicitly political mandate as a member of the Puerto Rican militant organization the Young Lords, which had formed in 1969 a year prior to the debut of Right On! Throughout the film Luciano sports the ubiquitous beret adopted by the Lords following the military-style dress code of the Black Panther Party. Now in his late 60s he continues to “serve the people” as a well-known New York City community activist, frequent political commentator, and media producer. David Nelson, now in his 70s, changed his name to Dahveed Ben-Israel and then to Dahveed Nelson and has relocated to Ghana where he continues to recruit other African descendants to develop ties with the West African country through repatriation. And finally Gylan Kain, who is also well into his 70s, has relocated to Atlanta where he continues to (re)create under the nom de plume “Kain the Poet: a Rap-Rock-Indie-jazz-holy roller-existential-blues poet.” And channeling the Yoruba trickster god Eshu in the form of an Afro-surrealist bluesician, he wrote on his now defunct website: “Ye that hath seen me, hath seen Baby Kain and no one cometh to my father except by me. My name is Kain The Poet and I just got here!”

Perhaps it was less obvious in the patriarchy-thick days of the 1960s that there is far more at play and useful than a simple articulation of Black or Puerto Rican Nationalism, the pleasures of machismo, and a black masculinist ordering of the world in Right On! Looking and listening closer we perceive an attempt to capture in poetic form a style and delivery, lessons in fire-spitting, a sense of the possibility of speaking the self and community, or the self as community out of erasure, a stretch away from the fodder mill of American empire and western racial capitalism—of at once holding both the possible and the impossible in the palm of a clenched fist turned Black Power salute and screaming “RIGHT ON!” Yet, as the chocolate cities of America melt under the heat of gentrification, alongside the spatial and bodily dislocation of the prison industrial complex, resurgent and violently narrow white nativism, and the persistent indifference to black suffering despite the widespread appeal of Black Lives Matter, it remains to be seen what sorts of poetic weaponry will be necessary in the 21st century.

Christopher M. Tinson is an Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History at Hampshire College. He is the author of Radical Intellect: Liberator Magazine and Black Activism in the 1960s, published in October by University of North Carolina Press.

References

K. Willie Kgositsile, “Towards a Walk in the Sun” (poem). Black Fire: An anthology. Edited by Neal & Baraka, 1968. “The only poem you will hear will be the spearpoint pivoted in the punctured marrow of the villain; the timeless native son dancing like crazy to the retrieved rhythms of desire fading into memory.”

Rod Hernandez, “Latin Soul: Cross-Cultural Connections between the Black Arts Movement and Poncho-Che,” in New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement, edited by Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie Crawford (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 333-48.

Michelle Joan Wilkinson, “To Make a Poet Black: Canonizing Puerto Rican Poets in the Black Arts Movement,” in New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (2006), 317-32.

Jared Sexton, “Racial Profiling and the Societies of Control,” in Warfare in the American Homeland, edited by Joy James (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 197-218.