Daniel Kane's "Poetry and Punk Rock in NYC"

Reviewed by Louie Dean Valencia-García

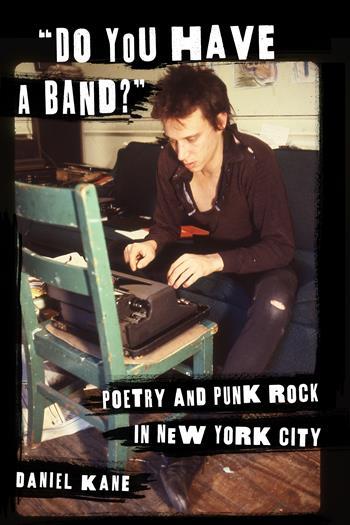

“Do You Have a Band?”

Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City

By Daniel Kane

New York: Columbia University Press, 2017

Punk culture, like most subcultures, depends upon mythology. These mythologies are built around people, spaces, and events of the past, often reused to create something new — pieced together in what cultural theorist Dick Hebdige calls “bricolage.” Daniel Kane’s “Do You Have a Band?”: Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City attempts to demystify one particular aspect of the early days of the New York City punk scene: its connection to the New York poetry scene. In a way, this work functions much like a sequel to the author’s 2003 work, All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s, focusing primarily on the well-known. Kane gives just about equal time to both analysis of poetic influences and to biography, intertwining them in his narrative. Do You Have a Band? is divided into chapters that focus on The Fugs, Lou Reed, St. Mark’s Poetry Project, Richard Hell, Patti Smith, Eileen Myles, Dennis Cooper, and Jim Carroll. The author’s decision to focus on these individuals and places does not surprise — they all fit into a sort of mythologized New York proto-punk canon. When given the opportunity to talk about punk-poets outside the canon, Kane avoids researching the less-famous individuals who were part of the scene. This focus on the select few is particularly noticeable in choices such as Kane’s decision not to elaborate upon the lesser known poets that figured into the mimeograph punk poet magazine published by Richard Hell — leaving the mythology of the New York punk-poetry scene largely intact.

In his opening salvo, Kane targets the mythology surrounding the influence of nineteenth century Symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud, whom punk poets Lou Reed, Richard Hell, and Patti Smith have all credited as a crucial influence. Kane rightfully argues scholars should look not just at these mythologized figures of yore, rejecting the notion that the French maudit poets were some magical font from which punk poetry came. Kane prefers to look at what he contends to be an active East Village poetry scene that influenced punk music. Kane argues:

Do You Have a Band? does not deny that there are resonances between the band Television and French symbolism, [or] the rhetoric of punk rock and Situationist International slogans… I focus particularly on the direct and dynamic interactions that musicians had with the poets and poetics of the New York School — from Frank O’Hara to second- and third-generation New York School writers including Anne, Waldman, Ted Berrigan, and Eileen Myles.[1]

Despite this opening criticism and explanation, Kane does not escape the influence of the nineteenth century poets, referencing them often throughout his book. Although Kane attempts to shift the focus away from Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and company, he still focuses on well-known protagonists who, themselves, embrace the Symbolists wholeheartedly. It is impossible to divorce Patti Smith from Rimbaud — especially given the fact that she now owns Rimbaud’s childhood home. Punk poet Tom Verlaine adopted the last name of Rimbaud’s lover, Paul. Richard Hell and Lou Reed also have exclaimed their passion for Rimbaud. Kane could have potentially made a much stronger case against the influence of the Symbolists on punk-poetry, but that would have required consideration of poets outside of his canon.

New York, and particularly the bohemian East Village of the 1960s and 70s, was a central place from which punk cultural emerged. Recent works such as Ada Calhoun’s St. Marks is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street give more of an understanding of the East Village scenes, beat, underground, and punk. Kane’s work, fundamentally, is a literary analysis of those proto-punk poets and their influences on each other and not a cultural history of the New York punk scene. He successfully ties Reed, Smith, and Hell to Anne Waldman, Ted Berrigan and others of the New York School. Initially, Kane expands the early New York punk era to include the mid-1960s to the 1970s, where Reed and Andy Warhol are folded into the story of punk more explicitly.[2] It would seem, in Kane’s narrative, if Patti Smith is the godmother of punk, then Lou Reed is its godfather. This understanding works when limiting the scope to New York — if broadened, just slightly, as Stephen Duncombe’s White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race shows us, we have to take into consideration the working class and immigrant neighborhoods of the United Kingdom as another tributary to punk. By placing punk’s intellectual roots where the author does, we come across a much more white-washed, middle-class construction of punk — which would be an unfair depiction of punk culture more globally. How can we complicate this fairly straight-forward narrative to more effectively incorporate issues of race, class, and gender — particularly essential given the history of the East Village? Where do places like the Nuyorican Poets Café (founded in 1973) fit into this history? Or 1970s Loisaida Puerto Rican punk bands such as The Stimulators? Because of omissions like these, Do You Have a Band? is incomplete even in its goal of locating the intersections of poetry and punk in New York City. That is not to say it is not a worthwhile book, just that it barely scratches the surface of the work that can be done.

The author takes particular interest in the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, as well as venues such as Max’s Kansas City, Tenth Street Coffeehouse, and others. William Burroughs and Allen Ginsburg also feature prominently, being seen regularly at mythic punk locale, CBGB’s. In these vignettes, Kane’s argument is made clear; there certainly was overlap between the punk and poet scenes. Early in the book, Kane investigates the lower-east side experimental poetry-rock group, the Fugs — a group formed just before the Velvet Underground came together. The group wrote songs such as “Coca Cola Douche” and published mimeographed magazines such as Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts and pamphlets such as Fuck God in the Ass. Clenching his argument, Kane points to a quote from undisputed punk rock legend Richard Hell’s own belief that Fug’s member Ed Sanders was “an inspiration to anyone who ever wondered if ever they could be a rock and roll musician.”[3] Sanders looked up to poets of the Beat generation, and, according to Kane, wanted to “transmit as much of their love for avant-garde poetry to as wide an audience as possible. Becoming rock ‘n’ rollers was simply the fastest and best way forward.”[4] The author further points to the groups’ album, The Fugs First Album, which Kane argues even looks punk — comparing it to a Jacob Riis’s photograph, Bandit’s Roost — presumably this punk aesthetic is seen in the menacing poses of the men in both photographs (though Kane does not explicitly explain why.) The aesthetic of the Fugs was anything but the pastoral imagery common of the 1960s-folk era. This argument, if pushed just a bit further could be read as a precursor to the punk obsession with “filth” and vulgarity — though Kane does not make this leap. Such an analysis of filth could have been an excellent place to analyze the ways that punk culture (and bohemian cultures more generally) is attracted to that which offends bourgeois sensibilities.

Despite the promise to look away from Rimbaud, in Do You Have a Band?, Kane explores the influence of Rimbaud on Richard Hell, noting aesthetic presentation — hair, clothing.[5] Is this part of Kane’s understanding of what is poetic? Patti Smith was also inspired by the biographies of European writers for her “lifestyle and performance choices” because, as Kane explains, “their wild lives couldn’t be matched by the contemporary crop of American poets.”[6] Kane tries to describe the ways in which Hell was not like the Symbolist poets, known for first writing his music first, and then writing his poetry to that music. This is an important point; however, Kane misses the opportunity to draw a connection to the Beat poets, also known for listening to jazz beats for inspiration. Such an argument, could even have refocused Kane’s initial thesis that punk drew from contemporary New York poets (and musicians). Could we expand this argument to include the influence of black jazz musicians as well? This would be a particularly interesting question given Caribbean music’s influence on British punk — a transatlantic story.

In a field so dominated by memoirs — Patti Smith, Richard Lloyd, Richard Hell, Jim Carroll, Kim Gordon, John Lydon are some examples — it is always nice to see a scholarly contribution to supplement those rich, and well-received, works. Kane’s work does what it sets out to do — connecting punk to poetry in New York City. What the work does more successfully is leave a path open for scholars to investigate these overlapping scenes further — to more effectively consider the diversity of participants of the New York punk and poetry scenes.

Louie Dean Valencia-García is an Assistant Professor of Digital History at Texas State University and editor for EuropeNow. His first book, Antiauthoritarian Youth Culture in Francoist Spain: Clashing with Fascism, explores the role of underground and punk culture in creating pluralistic spaces under the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco (forthcoming from Bloomsbury in May 2018).

Notes

[1] Daniel Kane, “Do You Have a Band?”: Poetry and Punk Rock in New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 2–3.

[2] Ibid., 6–7.

[3] Id., 20.

[4] Id., 23.

[5] Kane, 91.

[6] Kane, 134.