Why the British Lost: An Interview with George C. Daughan

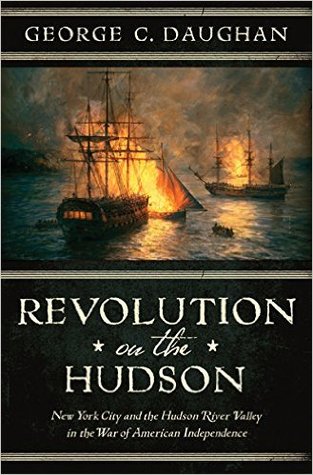

Today on Gotham, editor Nick Juravich interviews George C. Daughan about his recent book, Revolution on the Hudson: New York City and the Hudson River Valley in the American Revolution.

Let's start with the obvious question — what motivated you to write this book?

The book came from my study of early American history, which I began in the middle of the 1990s. Previously to that, I had been a professor at some universities, but I had left teaching and writing and had gone into business. When I sold my business in the 1990s, I began my work on early American history full time, with no distractions. I spent years, really, just reading. One of the things that struck me was that, so far as the Revolution was concerned, the naval aspects of it were just left out. There was very little written about it. When I first discovered this, I thought that I hadn’t done enough work, that of course there’d be books, but that wasn’t the case. So I started reading everything I could about the naval aspects of the war. I discovered that they were very important, and that the histories we ordinarily read had left them out because their authors had not studied them, and had not seen how important the naval aspects of the Revolution are, from beginning to end, from Lexington and Concord to Yorktown. The naval aspects of the Revolution were equally important as the land side of it. I began writing about this, and I think my reviewers were a little puzzled because it really was new territory. But one person who recognized it early on, of course, was George Washington.

And why focus on the Hudson?

My main example was always the Hudson. The Hudson fascinated me, because literally everyone who wrote about the Revolution believed that the Hudson was of enormous strategic importance. Washington did, all the British politicians and the king did, and later historians did. They believed the Hudson was the key to victory for the British, that if they could control the corridor from New York City to the Saint Lawrence, New England would be cut off and the Revolution defeated.

At some point, I knew that I was going to write a book explaining that this simply wasn’t true. It was not only a strategy that could never have worked, that being fixated on it actually cost the British the war. I focus on the great naval battle on September 5, 1781, prior to Yorktown off the Virginia Capes, in which the French bested the British. I believe their defeat there was intimately connected to the Hudson. That was my conclusion.

One of the historians who studied this as much as me was Thomas Fleming, who was a fan of mine from the beginning. He liked my first book, and loved this one. He honored it as the best book on the Revolution for 2016 at his New York Revolution Roundtable. Fleming passed away last summer, but I wish he’d had a chance to see my forthcoming book, which demonstrates that there was a naval component to Lexington and Concord. Tom was a great human being, and an old swabby (in the Navy in World War II).

And how did the British obsession with controlling the Hudson actually cost them the war?

What was wrong with the Hudson strategy? One of the people who thought the way I do about the Hudson was the British naval commander Lord Howe. Sadly, there’s no good biography of him, in part because there is so little interest in the naval side of the Revolution. Howe was one of the great British admirals; Horatio Nelson thought he was the best. Lord Howe and his brother, General Sir William Howe, were supposed to carry out the King’s plan to make quick work of the Revolution by gaining control of the Hudson-Champlain corridor to Canada. When Howe got here and took a look at the whole situation, he thought it was a fantasy, that the navy simply couldn’t do it. The warships that he had couldn’t begin to do all the things he was supposed to do on the Hudson. So he and his brother never tried. They of course couldn’t tell the king what they planned, and historians have criticized them for not carrying out the King’s strategy. In 1776 and 1777 they just did not attempt to meet a British army coming down from Canada at Albany. It’s never been said anywhere, but the fact was that the brothers thought that this was a sure way to lose the whole war.

Even if they had tried, it could never have worked, in the sense of controlling the Hudson and the territory between New York and Montreal. Something they knew, which I point out, that the King and historians never do, was that the population north of Westchester was hostile. How were you going to possibly control the Hudson if the population all the way to Manhattan was hostile? The Howes thought you couldn’t do it. A big part of their strategy in New York City and the lower Hudson, in fact, was to win over the population. This was not the King’s strategy. They wanted a political strategy, but they never got one. They agreed with me, but they never wrote it down anywhere. People then and now have noticed that they didn’t carry it out, but have criticized them and laid it to their stupidity. They don’t, as I do, think they were correct. In 1778, the Howes resign. They both go home and have to fight political battles in Parliament, because they became scapegoats for the lack of a quick victory.

Interesting. So how else might studying this naval history help us better understand the Revolution?

So, the story of the Revolution goes on. Fast forward to Yorktown, where there was an important naval battle, the Battle of the Virginia Capes, on September 5, 1781. Lord Cornwallis was with his army, and he was expecting naval support from New York. He was unaware that there was a big French fleet coming up from the Caribbean. This French fleet came up, and it appeared off of Yorktown, and Cornwallis was flabbergasted. The French had twenty-eight battleships, led by a French admiral named de Grasse. He was not their best. He would never have stood up to Howe. The British fleet, under Admiral Thomas Graves, is delayed, and does not know that de Grasse is there yet. Graves thinks de Grasse only has fourteen battleships. Graves is rushing there with seventeen battleships.

Graves loses this decisive battle of the war, which takes place on September 5. It would’ve been won if Lord Howe had been there, or if Admiral Rodney had been the commander. They were the best admirals that Britain had. Howe was gone, and Rodney did not appear with his fleet at Virginia Capes. Rodney knew he should have been there, but he was sailing home to England. Back in September of 1780, he’d come to New York City with his fleet, and discovered when he arrived that the British army and navy commanders in New York City hated each other. At that time, Benedict Arnold was about to hand over West Point, and Rodney thought the British would control the Hudson and win the war. After Arnold ended up in New York City, he and Rodney remained committed to taking West Point, but General Clinton decides not to pursue West Point, for reasons that are not clear. Rodney and Arnold were furious. Rodney had become so committed to the old Hudson strategy that he thought Clinton, by not attacking West Point, which Rodney and Arnold believed would give them control of the Hudson and win the war, could never be trusted, and he would have nothing more to do with him. Rodney took his fleet and left for the Caribbean. He says he was not interested in fighting alongside Clinton. Rand losing alongside him. In other words, this crazy Hudson strategy undermined British command at a decisive moment.

... I had so much fun writing this book.

Ha, well, that brings us to process and source questions. How did you go about the writing? And when you say naval history gets left out, is that because of the available evidence? Is the source base different?

Ships of that era were so different that for historians of the Revolution to get into that whole business would require a huge education, a huge commitment of time, getting to know what exactly was going on and the lay of the land. It would almost be like having to learn Sanskrit.

One of the people who wasn’t in that situation was Samuel Eliot Morison. But he had so many demands on his time that he could never write as much about it as he wanted to. There were just too many people with too many things for him to do. When World War II started, FDR, who had a big interest in the Navy, and who saved the US Navy in the 1930s, called in Morison and said, “You’re going to write the naval history of the war. You’re going to be an admiral, and I’ll give you a staff. Any questions?” Morison asked for only one thing, his approval to be in every theater. He wanted to see the whole thing in order to write it properly. FDR said yes, and Morison was everywhere. He and his staff wrote the long history of the war. He wrote one book on John Paul Jones, but he couldn’t do the naval history of the Revolution. He just never got around to it. There are two Samuel Eliot Morison awards for historians, and I am the only historian who’s won both of them. I just wish the old man could have been around to see it.

Read more about George C. Daughan's Revolution on the Hudson here.