To Build a Mature Society: The Lasting Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Beyond Vietnam” Speech

By Kristopher Burrell

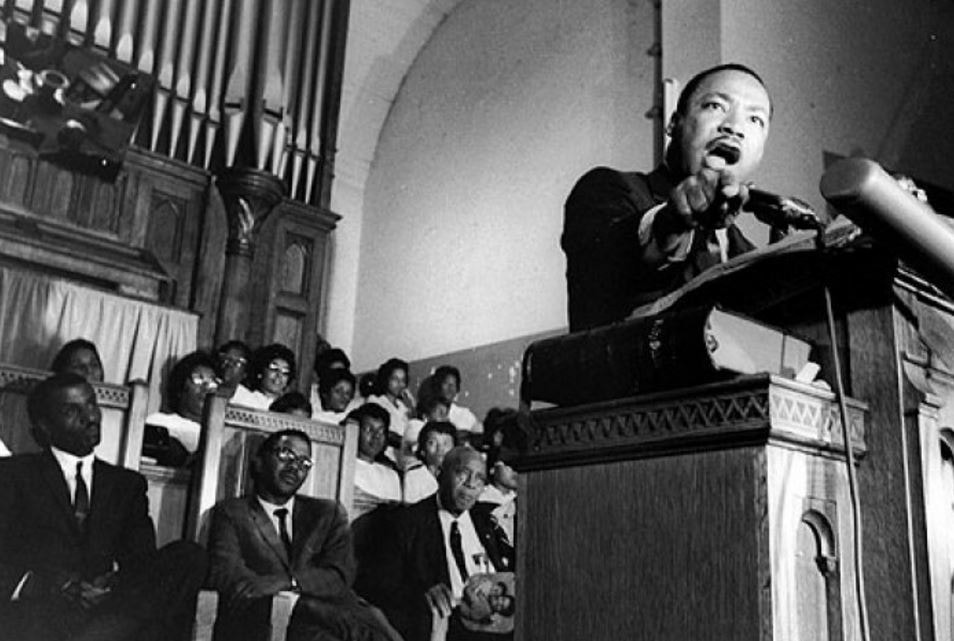

At Riverside Church in Harlem on April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his assassination, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a blistering and sophisticated critique of U. S. intervention in Vietnam. His “Beyond Vietnam” speech was prescient in ways that continue to haunt our society into the present day.

The speech upset many people and King was accused of wading into intellectual and political territory he was ignorant about. However, King’s experiences confronting poverty and structural discrimination in the North and West showed him the inextricable link between military involvement in Vietnam and the inability to eradicate social ills at home.[1]As King spoke about the virtues of nonviolence for bringing about lasting social change, the young people he encountered in places such as Watts and Chicago and Newark pointedly—and King said “rightly”—called attention to U. S. intervention in Vietnam as a counter argument to his position. King said, “Their questions hit home, and I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettoes without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today: my own government.”[2] Although King had long been opposed to warfare, he decided it was necessary to be unequivocally and outspokenly opposed to the Vietnam War in order to remain true to his moral beliefs, a relevant crusader for human rights, and a true patriot in the battle for the “soul of America.”[3] For King, nothing less than the future of America, indeed the world, hung in the balance.

King actually gave a sort of “dry run” of this critique of U. S. involvement in Vietnam in 1965, but according to Michael Eric Dyson, King was “soundly defeated” as members of Congress, the national media, and civil rights leaders aligned against him. The board of his own Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) issued a public letter stating the SCLC did not share his view on the war.[4] “Senator Thomas Dodd of Connecticut, a close ally of [Lyndon] Johnson, attacked Dr. King and cited an obscure 1799 criminal statute, the Logan Act, that prohibited private citizens from interacting with foreign governments” as a way to try and silence him.[5]

By early 1967, however, pictures of Vietnamese children horribly burned by napalm profoundly affected King.[6] As he would ultimately say at Riverside in agreeance with an official statement from Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam, the group that invited King, “A time comes when silence is betrayal.”[7] King spoke against the war in February of 1967 in Los Angeles, but “The Casualties of the War in Vietnam”[8] was only moderately reported on. And even the address at Riverside was intended to be a proverbial “soft opening” for an address he was to give ten days later at the United Nations, where Stokely Carmichael and other black radicals would also be in attendance.[9] However, not even what had happened in 1965 fully prepared King for the hell he would catch after the “Beyond Vietnam” speech.

King agreed to go to Riverside Church because “his conscience [had left him] no other choice.”[10] King and his co-writer Dr. Vincent Harding crafted the address he delivered on that spring evening, to an overflowing crowd of more than 3,000. When King gave the speech, he did not deviate much from the text, and he delivered the speech without the sonic flourishes that characterized his more celebrated addresses and sermons. Rather, King chose to deliver the address more as “he was speaking a dissertation;”[11] more somber in tone, as if imploring the listener to focus only on his words, and not get swept up by his delivery. King issued a dire warning to the Lyndon Johnson administration, to black and white northern liberals, and to the country about what continuing to fight this war was doing—and would do in the future—to the country. He wanted nothing to obscure or overshadow his message.[12]

King’s speech had three sections. In the first, King did three things. He explained why he was speaking at Riverside, addressed the many liberals who questioned publicly criticizing the war and the Johnson administration, and drew the apt connection between the escalating amount of money being devoted to the war and the declining amount of money being allocated to anti-poverty programs at home.

In addressing his “allies” who wondered why King was taking such a strong public stand in opposition to the Johnson’s administration’s foreign policy, in light of the things Johnson’s administration had done for African Americans and the poor, King said those people clearly did not know him very well, nor how dangerous a world it was. As King said,

many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path… ‘Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King?’ ‘Peace and civil rights don’t mix.”… And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment, or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest they do not know the world in which they live.[13]

King understood it was necessary to have a broader view of morality and struggles for justice around the world in order to improve the condition of humankind.

King then showed how continued involvement in Vietnam placed an unequal burden on poor people of all races. Not only were poor Americans fighting in larger proportions because they were not in college or eligible for other kinds of exemptions, but the domestic programs designed to help people escape poverty were being slashed to finance the war. King said, “A few years ago… [i]t seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor, both black and white, through the poverty program… Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched this program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war.”[14] King argued the U. S. government was being cavalier with its use of military force and that the gravity of the destruction being caused around the world was not being fully realized.

King went onto say,

Perhaps a more tragic recognition of reality took place when it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population. We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem… I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.[15]

King increasingly viewed the war in Vietnam as an attack on the poor in the United States. The war was both being financed on their backs and perpetuating continuing cycles of poverty. The violence the U.S. Government was purveying was not just occurring in Vietnam, but also here at home.

As King transitioned into the next section of his address, he reiterated his opposition to the war as a child of God and person of faith. He believed any good Christian had to morally object to the war. King also summarized the trajectory of U. S. involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967, and critiqued the American government’s motivations for being there. He inhabited the perspective of the Vietnamese peasants caught in the crosshairs of the political and military battles destroying most everything they held dear.

King prodded the government and forced the audience to consider difficult questions about American involvement in Vietnam. King said, “What do the peasants think as we ally ourselves with the landlords and as we refuse to put any action into our many words concerning land reform?... Where are the roots of the independent Vietnam we claim to be building? Is it among the voiceless ones?”[16] King’s answer was a resounding “no.” He argued the U.S. was crushing the potential for a non-communist independent Vietnam. U.S. foreign policy and military action was eliminating the potential basis for any kind of constructive alliance between the Vietnamese and U.S. governments.

What reason did the Vietnamese people have to trust the U. S. government? The United States wanted Vietnam to become a democratic nation, but King made the point that the government intentionally mischaracterized the opposition movement to remove the dictatorial leader in South Vietnam as predominantly communist, when they were not. The U.S. government censored the press in South Vietnam. The National Liberation Front in South Vietnam was to be excluded from the U.S.-led peace negotiations. And the American government had previously lied, saying Ho Chi Minh, the leader of North Vietnam, had never reached out to the U. S. in search of peace when there was concrete evidence to the contrary.[17] The American public had been lied to about the government’s intentions and actions in Vietnam.

In concluding the second section of the speech, King also expressed concern about the war’s effects on American troops. Here, King articulated the real benefit of nonviolence, “when it helps us to see the enemy’s point of view, to hear his questions, to know his assessment of ourselves. For from his view we may indeed see the basic weaknesses of our own condition, and if we are mature, we may learn and grow and profit from the wisdom of the brothers who are called the opposition.”[18] King also argued that continued involvement in Vietnam was diminishing U.S. standing in the world. “If we continue, there will be no doubt in my mind and in the mind of the world that we have no honorable intentions in Vietnam.”[19]

And with that warning, King went into the final section of his address. He gave concrete ideas about how and why the U.S. should withdraw its troops, called for religious leaders to speak out more courageously against the war, and talked about what Americans needed to do to create the kind of society the U.S. professed to be. King listed five things the U.S. government should do immediately to disentangle from Vietnam, including ending all bombing; declaring a cease-fire to create the atmosphere for potential negotiations; halting the troop buildup in Thailand and Laos; including the North Vietnamese government in the negotiation process for a unified Vietnam; and setting a date for the removal of all U.S. troops in line with the Geneva Accords.[20] Removing the American presence from Vietnam would, nevertheless, require true humanitarian assistance to the nation. He called on the U. S. government to provide asylum to all who sought it, extend medical supplies to Vietnam, and provide reparations for the damage that had been caused.[21]

King offered these policy recommendations for getting the U.S. out of Vietnam in as moral a way as possible, but he was not done with his audience because “[t]he war in Vietnam [was] a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit… [there needed to be] a significant and profound change in American life and policy.”[22] As King continued on the need to effect profound changes in American life and policy, he actually returned to ideas that he had been developing for years; that “we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”[23] Americans had to really address what it means to be “just,” both in terms of our domestic society and the kind of world that we were making.

King left the pulpit at Riverside to a standing ovation, but the reaction outside those church walls the next day was swift and scathing. Nearly 170 white and black newspapers across the country denounced him and the speech.[24] The New York Times called King’s statements “facile,” declaring it “wasteful” for King to divert his energies and talk about Vietnam because the civil rights movement needed to confront “the intractability of slum mores and habits.” The Washington Post called King’s recommendations “sheer inventions of unsupported fantasy” and opined that, “many who have listened to him with respect will never again accord him the same confidence.” The Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper, warned that King was “tragically misleading” African Americans about the incredibly complex issues associated with the war.[25] President Lyndon Johnson rescinded an invitation to the White House[26] and authorized the FBI to increase its surveillance campaign to discredit and destroy him.[27] Other civil rights leaders spurned him. Even the NAACP issued a statement disavowing King’s sentiments.[28]

All of these denunciations show that the liberal civil rights establishment, which included the Democratic Party, many media outlets, and civil rights organizations, were only comfortable with the King that spoke of dreams and racial progress, and allowed liberals to remain secure in their condescension toward the South, without having to examine their own assumptions or the policies they had crafted. The liberal establishment did not want to hear a black public intellectual who was not talking about the foibles of black people or how much progress black people had made. And civil rights organizations did not want to endanger relationships with the federal government or white philanthropic organizations that provided much of their operating funds.

King expected the backlash, and it certainly disappointed him, but he was not “soundly defeated” as Michael Eric Dyson said of him in 1965. As historian Benjamin Hedin wrote, “The Riverside speech seemed to unlock something in him, and he would no longer concern himself with political allegiance and popular opinion.”[29] And liberal policies only proved, rather than dispelled, King’s arguments. Liberals who had previously supported the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the mid-1960s became the same people supporting laws, such as the Safe Streets Act in 1968, that began the militarization of municipal police forces and put more money into building up the law enforcement and criminal justice apparatuses than had ever been allocated toward Lyndon Johnson’s anti-poverty programs.[30]

In the fifty years since, the U. S. has entered into new war fronts across the world. And the Democrats have often stood in lockstep with the Republicans in supporting increasing funding for the military industrial complex, even as the wars extended to the home front in the forms of “wars” on drugs, crime, and the poor.[31] Increasing funding for military intervention overseas has occurred almost without fail, while attacks on the social safety nets of Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and other programs have only ramped up over the last fifty years—mostly from Republicans—and are only getting stronger every year.

Decreasing or eliminating funding to anti-poverty programs, while simultaneously increasing defense spending and allowing tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the top one percent of wealth holders is antithetical to the kind of society Martin Luther King, Jr. was working to create. It smacks of the same double-burden he described poor Americans facing back in 1967. And in light of President Donald Trump’s comments regarding immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America, in which he disparaged in racist terms those seeking to escape violence and persecution by coming to the United States, King would say we still have more maturing to do.

Kristopher Burrell is Assistant Professor of History in the Behavioral and Social Sciences Department at Hostos Community College (CUNY). His articles have appeared in the Western Journal of Black Studies, Radical Teacher Magazine, and the Encyclopedia of American Urban History. His chapter, “Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City’s Public Schools during the 1950s,” will appear in the forthcoming collection, The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North (NYU Press, 2019).

Notes

[1] Martin Luther King, “‘Beyond Vietnam,’ Address Delivered to the Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam, at Riverside Church,” A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (April 4, 1967), http://www.stanford.edu/group/king/speeches/pub/Beyond_Vietnam.htm, 2-3, Accessed on 27 December 2017.

[2] King, “Beyond Vietnam,” 3.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Michael Eric Dyson, “MLK: A Call to Conscience,” Tavis Smiley Reports, March 31, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/mlk-a-call-to-conscience/, Accessed on 27 December 2017.

[5] David J. Garrow, “When Martin Luther King Came Out Against Vietnam,” New York Times, April 4, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/04/opinion/when-martin-luther-king-came-out-against-vietnam.html?_r=0, Accessed on 27 December 2017.

[6] Garrow, “When Martin Luther King Came Out Against Vietnam,” New York Times, April 4, 2014.

[7] King, “Beyond Vietnam,” 1.

[8] Benjamin Hedin, “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Searing Antiwar Speech, Fifty Years Later,” The New Yorker, April 3, 2017, http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/martin-luther-king-jr-s-searing-antiwar-speech-fifty-years-later, Accessed on 27 December 2017.

[9] Taylor Branch, “MLK: A Call to Conscience,” Tavis Smiley Reports, March 31, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/mlk-a-call-to-conscience/.

[10] King, “Beyond Vietnam,” 1.

[11] Clarence Jones, quoted in Hedin, “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Searing Antiwar Speech, Fifty Years Later,” April 3, 2017.

[12] Eric Tang, “‘A Society Gone Mad on War’: The Enduring Importance of Martin Luther King’s Riverside Speech,” The Nation, April 4, 2017, https://www.thenation.com/article/a-society-gone-mad-on-war-the-enduring-importance-of-martin-luther-kings-riverside-speech/, Accessed on 27 December 2017.

[13] King, “Beyond Vietnam,” 2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., 2-3.

[16] Ibid., 5.

[17] Ibid., 6.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., 7.

[20] Ibid., 7-8.

[21] Ibid. 8.

[22] Ibid.

[23] King, “Beyond Vietnam,” 9.

[24] Robert Siegel, “50 Years Ago, MLK Delivers a Speech with Dark Vision of the World,” All Things Considered, National Public Radio, April 4, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/04/04/522632447/50-years-ago-mlk-delivers-a-speech-with-dark-vision-of-the-world, Accessed on 8 January 2018.

[25] Garrow, “When Martin Luther King Came Out Against Vietnam.”

[26] Tang, “‘A Society Gone Mad on War’.”

[27] Gary May, “Martin Luther King Jr.: Remembering a Committed Life,” HuffPost, March 19, 2014, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/gary-may/martin-luther-king-legacy_b_4612780.html, Accessed on 8 January 2018.

[28] Hedin, “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Searing Antiwar Speech, Fifth Years Later.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] Tang, “‘A Society Gone Mad on War’: The Enduring Importance of Martin Luther King’s Riverside Speech.”

[31] Ibid.