The Perils of Pearl Street - And a Taste of the Dangers of Wall Street: 1834-2009

By Alan Solomon

Pearl Street, New York c. 1834 - Looks innocent enough.

The ups and downs, scams and swindles, building booms and busts, the wisdom and folly of New York City’s business district. It was all happening in the early 19th century, and recounted in a semi-humorous novella of 1834, The Perils of Pearl Street: and a Taste of the Dangers of Wall Street by A Late Merchant (Asa Green)—a quintessential New York tale of aspiration and redemption (of sorts). The Sesquicentennial offers a time to reflect on this heritage.

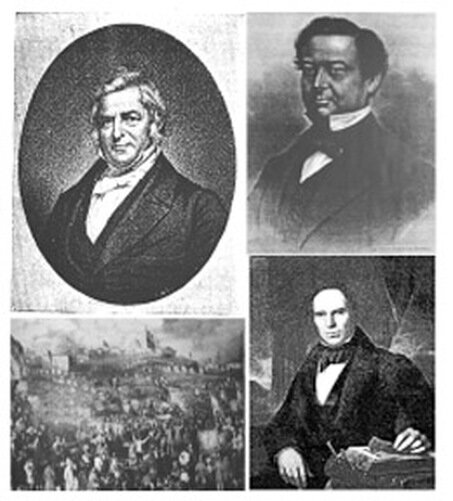

Manufacturers and Merchants, Revolutionaries and Revivalist Architects (Top left to right: William Colgate, A.A. Low (son of Seth Low Sr.), Rally at Birmingham, UK sandpit lead by Joshua Scholefield; Ithiel Town, revivalist architect and founder of country's first architectural firm, Town & Davis.

Our guide through the perils is “a late merchant” named William Hazard, with the story is set in the early Erie Canal era (1825-'30s), a period that would establish lower Manhattan as the commercial capital of the United States. Hazard moved to New York from an upstate village, a young man with dreams of becoming a merchant-prince on Pearl Street, the country’s wholesale hub for dry goods—carpets, wallpaper, crockery, lumber, upholstered furniture, mirrors, finished cloth, hardware, dishes and flatware, shoes, books, and on and on.

The story begins:

Of all the various professions, occupations, or employments of life, none perhaps afford greater vicissitudes than that of the merchant. None lead through more trials and difficulties; none expose their votaries to severer hazards of shipwreck, both in money and reputation.

Early merchants were intimately familiar with the street’s commercial perils, common enough to have slang expressions like Shinning, Drumming, Flying the Kite and the services of Peter Funk. The following provides a slight survey of tactics from the district, and their modern day equivalents.

Shinning

When a merchants debts accumulate—notes due to importers and auctioneers, rent, salaries to employees, living expenses, etc.,—and creditors failed to pay on time, or all together, a firm faced potential bankruptcy.

Hazard, and his business partner Alfred Launch (Launch & Hazard) found themselves in this bind. And like many others that were strapped for cash, fell back on Shinning, which meant “running about to ones acquaintances to borrow money to meet the emergency of a note in bank”. In the search for funds, the desperate funds seeker, losing sight of boxes, barrels, piles of bricks and other obstacles, was likely to bang up their shins.

When the individual arrives at a potential lender, they say “anything over?” By this they mean to ask if they have anything over and above their own debts—for a Bailout. Shinning appeared to be so regularly practiced that you could identify a merchant by the “…discolored and battered condition of their shins.”

In recent times, investment banks and the auto industry, facing collapse, resorted to this practice, nearly crippling their shins in pursuit of billions in bailout funds from the Federal government, the one lender that had, or at least could borrow, tax, or print “anything over.”

Drumming

Hazard gets off to a slow start in New York, struggling like generations of future newcomers, to find an entry-level clerkship, or even decent room and board. He eventually falls into a job ‘Drumming’, mercantile-slang for the soliciting of customers. The work was not considered very dignified by more

established Pearl Street merchants, who regarded active Drummers to be ‘very slippery fellows’. Hazard admits to making “awkward work at drumming.”

The practice usually amounted to scouting out hotels for country merchants, engaging the target in a pitch, and directing them to the “…most celebrated establishment in the dry goods lines of any house on Pearl Street.” The uninitiated country merchant was generally lead to low quality and over-priced goods, or to bid against the notorious Peter Funk, who could be found at many mercantile houses at the same time, helping to bid up prices at fraudulent auctions.

Modern sales and marketing is now a national institution, though practices and ethics vary widely. But even Pearl Street merchants or Phineus T. Barnum, who wrote The Humbugs of the World (1866), a mid-19th century line-up of scams, fraud, corruption and hoaxes, from spirit rappers and lottery sharks to false prophets and medical quacks, may still be stunned by the epic Ponzi Scheme at Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, where the ring leader established a network Feeder Funds that drummed up billions from imperiled clients, including sophisticated investors that were duped like unsuspecting country merchants. Madoff pleaded guilty to his crimes on March 12, 2009 at the U.S. District Court at 500 Pearl Street.

Flying the Kite

Another popular means of raising funds when debts came due and cash was short involved Flying the Kite. The well known practice was defined to be, “…a combination between two persons, neither of whom has any funds in bank, to raise money by an exchange of checks…each taking care to deposit funds before the regular bank exchanges.” It carried risk, but was not an uncommon maneuver, with a firm able to keep up the show for a long time, “… when all beneath was perfectly hollow.”

Although Wall St. in recent days may have looked like a Kite Flying festival, amid the worst financial climate in history, a major participant was AIG (American International Group). Executives of the venerable insurance giant parked their cars in an open lot adjacent to 215 Pearl St. But much of the troubles took root at the AIG Financial Products office in London, where the conditions were more favorable. Since the unit was not subject to American insurance regulations, drumming could go on with abandon, even if the complex derivatives that were sold far exceeded anything that AIG, the largest insurer in the world, could cover. The scheme is still under investigation for securities fraud.

Peter Funk

The services of Peter Funk were despised by some and loved by others, but he was well known among all merchants on Pearl Street. Described as “…a little, bustling, active, smiling, bowing, scraping quizzical fellow, in a powdered wig…”, and at the same time, a person who was always transforming. Funk was the era’s prototype for every kind of scam operator in the district. His core business was at the auction houses, where he’d position himself in the crowd, and keep bidding prices at a premium.

Peter Funk lives on, with his transformations multiplied, and his geographic scope gone national. In the first decade of the 21st century, he turned more of his attention to the real estate sector, consulting with investment and mortgage banks, the government, and the media to bid up property values. He worked around the clock as a sub-prime lender, created esoteric mortgage backed securities, greeted countless clients at open houses, and ran NO MONEY DOWN investment seminars at the Learning Annex. Funk even predicted the markets irrational exuberance, seeing values resting on a foundation of air, and unloading his portfolio before the perils hit.

Speculation

Hazard lost the battle to avoid the swindles of the mercantile trade, and eventually went into bankruptcy—twice. But with the prospect of retrieving losses, he tried his luck at stock speculation, experiencing “…a taste of the dangers of Wall Street”. [Note: The American stock market had just been established in 1825, and white collar law enforcement by the Fed, or oversight by the SEC were not yet instituted, and perhaps still].

An early associate introduces Hazard to “one of the most ingenious arts of modern speculation”, first selling, and later buying stock. Or otherwise betting that a stock price will fall—today known as ‘Selling Short’. Going on the advice of “shrewd calculating men that look deeply into cause and effects”, the partners are convinced that shares of the Mammoth Institution, held at the United States Bank, must go down (“…and pretty roundly too”). “Bears and Bulls!” exclaims Hazard when he hears this term for the very first time, and is then instructed by his advisor to not alert the Bulls, for there will certainly be a 10 percent price drop in the stock within a couple of months.

Hazard doesn’t let the opportunity pass. He puts up everything he owns (except for his clothes), and holds out for the two months, when he will no doubt arrive at “a safe harbor with all his sails spread”. Unfortunately, the stock of the Mammoth Institution refused to drop (“the bulls triumphed; the bears retreated to their dens”). Hazard was finished.

211 Pearl Street, New York

But the commercial and financial scene on Pearl and Wall was not without a counter-force, largely represented by established merchants that were philanthropists and populists—and often evangelical, during an early 19th century era of religious revival that historians have called the Second Great Awakening.

A surviving business building from the period, a five story brick and granite warehouse at 211 Pearl Street in lower Manhattan is a representative example. It was built for the soap maker William Colgate, the son of a political exile from England. He founded the American Bible Society, lead the volunteer fire department, and laid the foundations Manufacturers and Merchants, Revolutionaries and for the Fortune 500 company Colgate-Palmolive.

His commercial tenants were also early models of corporate citizenship. Seth Low Sr., a founder of Brooklyn, who was instrumental in opening trade with the far East; and a UK hardware merchant, Joshua Scholefield, who organized mass rallies in the Birmingham sands pits which lead to modern Democracy in England during the 1830s. The Greek revival style of the building is based on a design of the architect Ithiel Town for the Abolitionist silk merchants, Arthur and Lewis Tappan at 121 Pearl Street.

Facadicide on Pearl Street - no. 211 in Dec. 2007. Photo: Fabrizio Costantini.

In late 2002, the downtown block where 211 Pearl is located was slated for demolition. Preservationists responded with a public protest and appeal to the NYC LPC (Landmark Preservation Commission) for a hearing, with historian Paul E. Johnson calling the building “..a rare surviving relic of the process that transformed New York into America’s great city.”

The preservation campaign was lost – but not entirely. The facade of 211 and a mysterious brickwork symbol on its interior wall were preserved in an agreement with the real estate giant Rockrose Development, who were granted Liberty Bonds in exchange.

Questions about business ethics can be as complex as Pearl Street’s ancient and crooked street pattern. Preservationists nonetheless, said that 211 Pearl “…told a different kind of story about American business” as Burkhard Bilger wrote in The New Yorker Magazine (Mystery on Pearl Street, Jan. 08). “In 1831, the city was as corrupt as it would ever be, and men like Colgate were a deliberate counter-force to all that vice…211 was more than a charming vestige of old New York. It was proof that you could make a buck without screwing your neighbor.” There’s evidence that the historic counting house is something that Wall Street can use.

Alan Solomon has lived in New York since 1996. He is the owner of Solomon Wood Co., a dealer in reclaimed woods from dismantled buildings. He has experienced the perils of Pearl Street, though as a preservation advocate for 211-215 Pearl Street.