The Gilded Age in a Glass: From Innovation to Prohibition

By Zachary Veith

The Arctic

· Dash of Orange Bitters

· One-half Red Calisaya Bark

· One-half Sloe Gin

The Eldorado Bar in Lenox, Massachusetts, c. 1890-1915. Courtesy of the Lenox Library Association.

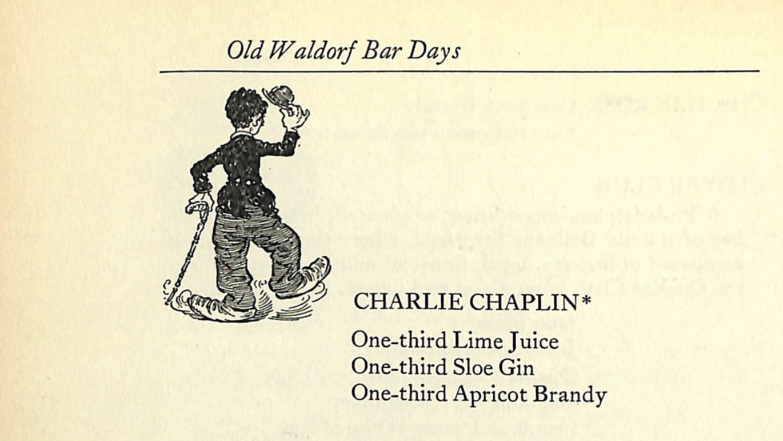

In the early 20th century, bartenders at the world-famous Waldorf-Astoria memorized 271 concoctions. Scores of signature drinks were dreamt up in honor of people and events: the “Arctic” to celebrate Peary’s discover of the North Pole, the “Coronation” to commemorate King Edward’s ascension to the throne, the “Commodore” and “Hearst,” honoring business tycoons, and even the “Charlie Chaplin.” Imbibing at the mahogany bar aligned oneself with the wealth and tastemakers of America; crowds of Wall Street bankers like J.P. Morgan, celebrities like Buffalo Bill Cody and Mark Twain, and the high-society elites all enjoyed more than a few of the bar’s signature cocktails.[1] Yet, for many, these spaces of inclusion and identity were off-limits.

Cocktails — the ingredients, the stories, the pageantry — can reveal more than expected about the Gilded Age. From the 1870s through WWI, America took its place among the industrial and political powers of the world. Great fortunes were amassed by railroad tycoons and oil magnets such as the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. A search for identity among the nouveau riche upper class grew out of the nation’s rapid modernization and unimaginable wealth. Identity — who you are and where you belong — became a major theme in the Gilded Age.

The era gave us some of our most famous cocktails as well; the Martini, the Daiquiri, the Old Fashioned, and more. Not every Gilded Age concoction was a hit, however. Some — such as the “Waldorf Astoria” (Benedictine and whipped cream), the “Bradley Martin” (crème de menthe and raspberry syrup), and the “Black Velvet” (champagne and porter) — we are more than glad to keep in the 1800s.[2] Yet those names — Bradley Martin, an infamous society host, Waldorf Astoria, the most elite hotel in New York, Daquiri, alluding to America’s global ambitions — all hint at identity and who is worthy of being remembered — and cheered too! These signature drinks (and countless more) served at the Astoria hotel or Fifth Avenue dinner parties reveal the loyalties of New York’s elite class and the familiar haunts of the millionaires.

Coinciding with a Gilded Age in cocktails, signature concoctions — full of ingredients and anecdotes — populated the landscape and secured the identity of a person, place, or idea for generations. Imbibing in cocktails became simultaneously a signal of inclusion to some groups or an act of defiance for others.

The Daquiri

· 2oz rum

· 1 oz lime juice, freshly squeezed

· ¾ oz simple syrup

In 1898, Col. Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders landed in the Cuban port of … Daiquirí! The Spanish American War had wide implications for America’s identity abroad — and our palette. Growing prejudiced views toward the Spanish combined with American spheres of influence over the western hemisphere, not to mention the explosion of the USS Maine, brought the US into a war with Spain over Cuban independence.[3] After a long summer of fighting, the Cubans technically gained independence, but the Americans remained and exerted massive amounts of control over the island.

Two years earlier, a mining engineer named Jennings Cox, while entertaining fellow expats at home just outside Daiquiri, stumbled into cocktail history by mixing sugar and ice with a local favorite of rum and citrus. Cox can’t take all the credit, however, as a version of this drink has existed for generations within the larger Caribbean.[4] Yet the concoction is emblematic of America’s increasing presence on the global stage and our aggressive colonial ambitions among the great powers of Europe in the New World.

William Astor Chanler is credited with bringing the Cuban cocktail to New York. As a member of the NY State Assembly, he sympathized with the Cuban struggle for independence, signed up as an officer in the US Army, and served through the war. Five months later, he was elected to Congress where he reversed his revolutionary thinking and instead advocated for the annexation of Cuba (as well as Hawaii and other territories). In 1902, he purchased several iron and copper mines in Cuba where he was introduced to the now-established “Daiquiri” cocktail. As a high society “clubman,” he popularized the cocktail in clubs across Manhattan.[5] The rum concoction remains as a lasting identifier of America’s colonial ambition and global reach during the Gilded Age.

The Manhattan

· Dash of Orange Bitters

· One-half Italian Vermouth

· One-half Whiskey

The clubs that Chanler and his elite peers were members of were ubiquitous in Gilded Age New York and are clear examples of belonging and not belonging. It was widely rumored that the Manhattan cocktail was invented in the 1870s and named for the Manhattan Club. In November 1874, so the story goes, Jennie Jerome was hosting a banquet for the newly elected governor of New York, Samuel J. Tilden, at the Jerome Mansion — home of the Manhattan Club. The drinks served — a mix of whisky, sweet vermouth, and bitters — were a hit, and club members began ordering the “Manhattan” across town in celebration of the banquet and their club. But, there’s some issues with the story. First, there are reports of bars a decade earlier mixing a similar drink in Manhattan. Also, Jennie Jerome was not in America at the time, but in fact in Europe and pregnant with her eldest son — Winston Churchill. Lastly, no women were listed as attending the actual Manhattan Club celebrations for Governor Tilden.[6]

Establishments like the Waldorf-Astoria's bar or Fifth Avenue clubrooms were exclusively a male space. Nineteenth century social expectations created a gendered division in drinking — where women were not expected to drink publicly. Harry Gene Levine called the saloon “the antithesis of the home,” adding these spaces were “symbol[s] of male power and privilege” and calls for prohibition signaled a direct challenge to gendered norms.[7] Women drank alcohol almost exclusively in the home.[8] It would be unacceptable for any women of good society to be seen publicly drinking.

The Gin Fizz

· Juice one-half Lemon

· One-half spoon Sugar

· One jigger Tom Gin

Mrs. Langtry taking donations in the NY Stock Exchange for her tea party, from “Prince of Wales New Social Dictator of New York’s ‘400’,” Evening World, February 8, 1900.

This gendered division in the world of cocktails landed socialite Ruth Livingston Mills in the middle of a trans-Atlantic scandal between English royalty and American elites. In February, 1900, British socialite and actress Lillie Langtry was recruiting patrons for her “tea party” in support of wounded British soldiers fighting in the Boer War. Snubbed for support by the likes of Mrs. Astor and Mrs. Fish, Lillie telegraphed her “mister” — the Prince of Wales. Soon, it was clear the future King of England would close the doors of English society to the leaders of New York society if they refused his mistress. Instantly, Langtry received the written approval of Mrs. Astor herself to be named a patroness. Next, Langtry was knocking on the door of Mrs. Mills, who would only accept her invitation after a footman delivered Mrs. Astor’s written note. The Evening World noted that “the swaggerest [sic.] women in New York [Mills, Astor, etc.] will help a number of actresses pour tea at Sherry’s” during the party.[9] One day before “The Concert” (as was it was known in the gossip columns), an uproar was brought from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. It had been reported that society leaders, including Ruth Mills and Mrs. Edmund Baylies, would “serve the seductive cocktail and gin fizz to all who cared to imbibe.” The WCTU notified the police, as there was a law against barmaids in New York at the time; not to mention the scandal that Ruth would SERVE drinks alongside actresses. “The spectacle” of men and women enjoying alcohol together in a public space, one WTCU leader noted, “would be degrading, would be a blot on the reputation of the women of this city.” Representatives for Langtry were quick to point out that, yes, a bar would be available to those who want to imbibe, but that society women would not be serving alcohol.[10] Nevertheless, Ruth Mills and Caroline Astor did not risk attending the event.[11]

The Bee’s Knees

· 2 oz gin

· ¾ oz lemon juice

· ½ oz honey

1902 advertisement for Heublein’s pre-made “Club Cocktail” targeting upper-class women drinking at home. Printed in Harper’s Weekly, November 22, 1902. Courtesy of HathiTrust.

Over a decade after the Langtry affair, in 1912, TheNew York Times investigated the tea rooms frequented by the elite classes of New York society. They found that society women could (and did) enjoy liquor in six out of eighteen Manhattan tea rooms examined. Two of them cryptically served “Russian Tea,” asking “How will you have it – with gin or whisky?” The informant elaborated that she was confident women could be served alcohol is all eighteen tea rooms — but you needed to be more familiar with the owners before that could happen. “Our women may want a bar, they even may use a bar, but not by that name – not yet” TheNew York Times article noted.[12]Not just New York either — tea rooms from Baltimore to Los Angeles were all found to serve cocktails to respectable society women.[13] This is in heavy contrast to the male-only barrooms and social clubs for Mr. Mills, Mr. Astor, and other millionaire men of the time.

Cocktail culture and the growing fight for women’s rights were entangled from the beginning. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union were a major force for both temperance and suffrage by the turn of the century. The WCTU saw their crusade for temperance as part of the larger women’s rights movement, including voting rights and workplace protections. Drawing from the public separation surrounding alcohol, temperance campaigns connected men with “demon rum” while women were symbols of temperance.[14] Because of their distance from alcohol and the effects of drink, women used moral arguments to fight for temperance and suffrage by the turn of the century. Essentially, if a husband is too impaired from alcohol, a woman should be able to vote for her family. Activists like Carrie Nation shifted from arguments to violent raids and undertook literal “saloon smashing” to drive their ideology home; her bail paid for by the WCTU. Ironically, Nation’s elevation to folk hero earned her the honor of a cocktail being named for her.[15] Years of campaigning from organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, along with financial support from teetotaler John D. Rockefeller, led to the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919.

Mockingly, the Los Angeles Times printed a recipe for “The Suffragette Cocktail” — sloe gin, French and Italian vermouth and orange bitters — noting “one makes a man willing to listen to the suffragette’s argument.”[16] At the turn of the century, women employed alcohol to argue for greater rights such as the right to vote. The New York State branch of the national WCTU organization, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, focused heavily on suffrage believing women could fight for greater prohibition at the polls instead of in the streets.[17] With the passage of the 19th Amendment, white women underscored their new equality through alcohol. The 1920s ushered in a new era of modern women publicly drinking in spaces — albeit “underground” in speakeasies — previously open only to men.[18] Cocktails like the “Bee’s Knees” became must-haves for every bar due to their popularity with women drinkers.[19] By the 1930s, women who ventured further into one of the last male spheres, politics, were labeled as “cocktail-drinkers.”[20] The barroom was no longer the male domain.

Charlie Chaplin cocktail recipe and illustration printed in A.S. Crocket’s Old Waldorf Bar Days (New York: Aventine Press, 1931), 128.

The Gilded Age began with innovation — the scores of cocktails created to commemorate and honor all aspects of NY society — and ended in prohibition — the outlaw of alcohol in the United States. In those few decades, cocktails represented inclusion in wealthy, male society while simultaneously excluding women from participation. Cocktails, like public monuments, told us who and what to commemorate and what was important in the moment — a new film star, a colonized island, or a bar-smashing activist. Societal shifts, from civil rights to temperance, were seen through what people were drinking as well. These landmark events — prohibition and women’s suffrage — underscore the end of the Gilded Age following WWI. Today, LGBTQ+ bars and Black-owned taverns, even local establishments with weekly events, speak to the old ideas of inclusion and wanting to belong in a place among equals.

“True happiness is gained by making others happy … however well-mixed a drink is, much of the flavor will be lost unless politeness is added. A true artist should infuse courtesy and quality into all his liquid pictures.[21]” - A. William Schmidt, The Flowing Bowl: When and What to Drink (1891)

Cheers!

Zachary Veith is a Historic Interpreter for Staatsburgh State Historic Site in Staatsburg, New York. He holds a B.A. in History from SUNY Geneseo and an M.A. in Museum Studies from University College London. A special thanks to the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation.

[1] Albert Stevens Crockett, Old Waldorf Bar Days (New York: Aventine Press, 1931), 24, 27, 36, 89-91, 101-106, 127, 140.

[2] Cecelia Tichi, Gilded Age Cocktails: History, Lore, and Recipes from America’s Golden Age (New York: New York University Press, 2021), 52, 75, 128.

[3] Will Shenton, “The History of the Daiquiri,” Bevvy, July 17, 2016.

[4] Shenton, “The History of the Daiquiri.”

[5] Lately Thomas, The Astor Orphans: A Pride of Lions (Albany: Washington Park Press, 1999), 168; Mitchell C. Harrison, ed., Prominent and Progressive Americans: An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography, Volume II (New York: New York Tribune, 1904), 41-45.

[6] Michael Pollak, “F.Y.I.: Jennie and the Manhattan,” New York Times, December 23, 2007.

[7] Harry Gene Levine, “Temperance and Women in 19th-century United States” in Research Advances in Alcohol and Drug Problems, Vol. 5, ed. Oriana Kalant (New York: Plenum Publishing, 1980), 60.

[8] Elizabeth Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up: The Influence of Women on the American Cocktail,” The Virginia Tech Undergraduate Historical Review 9, no. 1 (2020): 28-29.

[9] “Prince of Wales New Social Dictator of New York’s ‘400’,” Evening World, February 8, 1900.

[10] “Women Denounce the Langtry ‘The Concert’,” New York Times, February 13, 1900.

[11] “The Concert A Success,” New York Times, February 14, 1900.

[12] Richard Barry, “The Tea Rooms, Where Society and Busines Meet,” New York Times, December 1, 1912.

[13] Jan Whitaker, “Tea-less Tea Rooms,” Restaurant-ing Through History, August 6, 2017.

[14] Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up,” 29-30.

[15] Mary Jane Lupton, “Ladies’ Entrance: Women and Bars,” Feminist Studies 5, no. 3 (1979): 572-573.

[16] Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up,” 28.

[17] Lupton, “Ladies’ Entrance,” 573-574.

[18] Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up,” 28, 30; Lupton, “Ladies’ Entrance,” 578.

[19] Sholtis, “Shaking Things Up,” 28-32.

[20] Lupton, “Ladies’ Entrance,” 579.

[21] Tichi, Gilded Age Cocktails, 18.