The Darker Side of Civil War Service for African American New York Families

By Holly Pinheiro

Prior to the 1960s, most white historians outright ignored the wartime experiences of African American soldiers. Few white historians, including Dudley Cornish, discussed United States Colored Troops regiments, and their analyses took a largely military focus by cataloguing a regiment’s mustering in and out process, military engagements, deaths, and causalities. These white historians opted to avoid any substantive discussion of African American military service. African American historians, conversely, began examining African American soldiers almost immediately following the war and continued long after. Historians, such as William Wells Brown, Joseph Wilson, and George Washington Williams, sought to rightfully place the wartime experiences of African American soldiers at the center of their monographs. These scholars sought to humanize African American soldiers’ experiences and highlight the fact that their service was not only masculine patriotism, but also legitimized their claim for citizenship rights while simultaneously participating in ending slavery. Even with the breadth of scholarship that scholars continue to produce on the topic of African Americans soldiers during the Civil War, obvious gaps in the historiography remain. Who were these soldiers long before their service? How did these young men, the families, and local communities combat the onslaught of racism in Northern society in the antebellum era? Did their motivations to enlist reflect the idealism that advocates of enlistment championed during recruitment campaigns? How did military service negatively impact the Northern African American families left behind? These are crucial questions that are at the center of my research, and until now, remained unquestioned and unanswered. My objective in conducting this research is to humanize the individual soldiers and their families to show how war affected the front lines and the home front simultaneously — thereby revealing how Northern African American families experienced the Civil War. This research focuses on African American New York soldiers and their families because their lived experiences deserve scholarly attention if we ever hope to understand how the war impacted Northern society.

New York has received a great deal of coverage in regards to the Civil War--and rightfully so. The film Gangs of New York focused on the internal partisan, ethno-religious, class, and racial divisions ongoing in New York City that led to a Northern civil war within the Civil War.[1] Similarly, there is a wealth of scholarship from historians, such as Iver Bernstein, Jane Dabel, Ernest McKay, Carla Peterson, and others who bring to light the significance of the city and state during one of the defining moments of American history. For instance, Ernest McKay’s book, The Civil War and New York City, examines how a large proportion of New Yorkers opposed President Abraham Lincoln’s war policies, such as the enforcement of martial law in Baltimore, Maryland, or how the decision to enlist African American men into the Union triggered the New York City Draft Riots in 1863. Meanwhile, Jane Dabel’s book, A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York, and Carla L. Peterson’s monograph, Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City, collectively discussed the hardships that African American New Yorkers who, regardless of their social and economic standing, dealt with as racial discrimination denigrated all African Americans in nearly every facet of Northern society.[2]Collectively, these studies do an exceptional job of investigating and explaining how New York’s support of Unionism and ending racial discrimination was not assured during the Civil War.

To date, William Seraile’s, New York’s Black Regiments During the Civil War remains the key study that details the state’s three black regiments to serve in the Civil War — the Twentieth United State Colored Infantry (USCI), Twenty-Sixth USCI, and Thirty-First USCI — from their organization through demobilization.[3] But even though Seraile’s book is a guiding force in my own research, it remains unclear who the black soldiers were before or after the war. The soldiers are not given the opportunity to have their individual lived experiences shine through in Seraile’s monograph. Rather, they are only depicted during their service, and are lumped in together as one large group. Furthermore, the experiences of their families before the war remain unknown. When the Union League Club of New York, authorized by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, began calling African American men to enlist in the Union Army, that decision not only effected the potential recruits, but also their families and friends who were left behind. It is vital to not only humanize the soldiers and highlight their individual experiences, but also to explore their families’ wartime experiences as well.

Military records for the three regiments show 4,125 men attempted to enlist in a New York black regiment.[4] Only 224, or slightly 5.5 percent, of the African American soldiers that served in either the Twentieth USCI, Twenty-Sixth USCI, or Thirty-First USCI stated that they were born in the state of New York.[5] Even though African American New Yorkers represented a small portion of the regiments, their stories should be examined and highlighted by scholars.

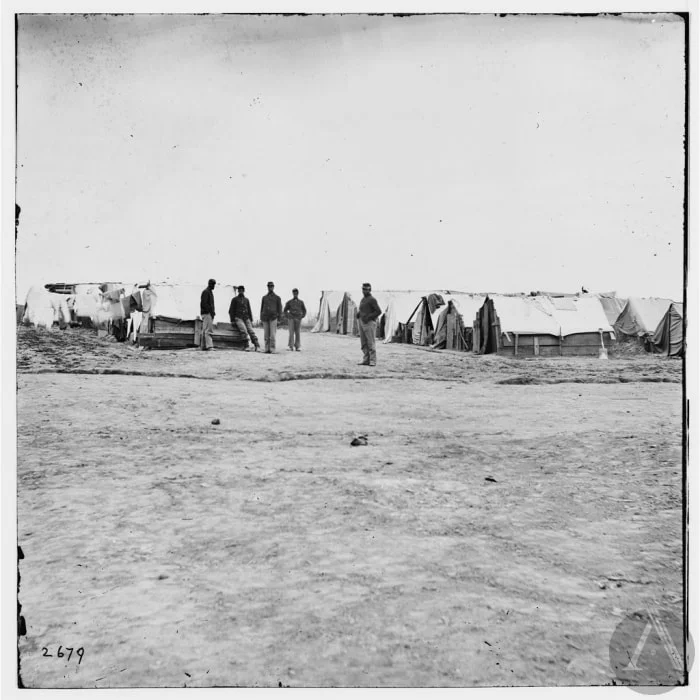

Previous scholarship highlights that the fatigue duty, or military manual labor which included ditch digging, building fortifications, creating latrine, and burying dead bodies, comprised the majority of work that the three regiments performed during their time in various theaters of war.[6]Union Army officials argued that African American soldiers were best suited to performing fatigue duty because most whites doubted that African American soldiers could perform well in combat and they believed that African American men could better perform physical labor in the humid and insect-infested Confederate territories. African American regiments performed the necessary fatigue duty while the white regiments engaged in fighting (and dying) in combat — a situation that not all white soldiers appreciated. Unfortunately for African American soldiers, the performance of fatigue duty in these horrendous conditions led to more soldiers dying from disease rather than the bullet, as medical historians, such Margaret Humphreys and Jim Downs, have shown.[7]

Of all three New York regiments, the Thirty-first USCI took part in the most military engagements, including taking part in the Battle of Cold Harbor, siege operations at Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia, and pursuing Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s forces to Appomattox Court House. It is worth noting that the Thirty-first USCI’s wartime experiences were the anomaly, and not the norm, for New York African American regiments.

Rather than solely focus on the military history of the regiments, my research examined twenty-five soldiers who were born in New York City before, during, and the war. One thing is clear about these men and their families, the prevalence of racial discrimination made life for them extremely difficult. Once the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 (FSA of 1850) passed, all African Americans’ freedom and civil liberties evaporated, along with their aspirations for citizenship rights. The FSA of 1850 was a clause in the Compromise of 1850 that protected the property rights of slaveowners, especially in the South, when slaves escaped to Northern free states.[8] Abolitionists, African American and white, were disgusted with the law threatening the lives of freeborn and fugitive African Americans by forcefully obligating Northerners to aid authorities in capturing suspected fugitives, sometimes without actual proof of their enslavement. Adult men, such as Leonard Kettle and John Freeman of the Twenty-Sixth USCI; young adults, such as Peter Vandermark of the Twentieth USCI; and, children, such as Eugene Bell of the Twentieth USCI, were all potential victims of the FSA of 1850 long before enlisting in the military. Even though none of the men or their families that I examined became victims of the FSA of 1850, that did not mean their lives were safe. Without question, the future soldiers and their families, were watchful of the personal safety of themselves and other African Americans when out in public. And they were aware of the collective actions of local African American churches and vigilance committees that protected numerous African Americans, including James Hamlet who was the first black man detained by the federal policy in New York City.

In addition to fearing possible enslavement, African American New Yorkers dealt with racial discrimination that hindered the economic opportunities for the majority of African Americans. There were of course affluent African American families, such the Guignons, who were able to able to circumvent various racial discrimination barriers and amass wealth.[9] But, they were the exception in Northern society. Most African Americans, including the families of future soldiers, were poor and depended on the wage-earning of every member of their household. A Northern African American household included non-kin and kin members, male and female, adult and even children who contributed with their labor, paid and unpaid, to keep their household economically stable. Numerous historians, including Patricia Morton, highlight that nineteenth-century middle-class whites idealized notions of gender claimed that only the adult men, usually husbands, were the sole wage-earners in the household.[10]

However, for many Northern African American households, the realities within their households rarely reflected the idealized notions that middle-class whites created. Eugene Bell, a future Twentieth USCI soldier, was only thirteen years old when he assumed the role of primary wage-earner of the household, in 1850, when his father abandoned their family. Bell would eventually work two occupations simultaneously as a coachman and waiter to provide economic stability for mother, Susan, and two sisters, Emily and Isador.[11] Eugene’s willingness to forgo achieving a formal education did not mean that their family devalued scholastic endeavors. Federal Census records reveal that Isador attended a racially segregated public school when she reached school-age. Even though records do not state it, it was likely that Susan and Emily contributed to their households with their unpaid labor, as countless women of all races did.

Even when an African American husband and father attained employment, such as Spencer Mingo, that did not mean that he lived by the standards that middle-class whites idealized. Spencer’s work as a laborer was never enough to keep his household of six economically stable, and forced William, a future soldier in the Twentieth USCI, to find work at a farm laborer once he was old enough to find employment.[12]William’s pension records provide testimony from numerous neighbors stating that William’s additional wages were essential to his family’s economic survival. And this continued even when he lived with his employer but still sent a portion of his wages to his family.

Racial discrimination made every individual in the households of African American New York families, like the Mingos and Bells, vital. African American men and women, adult and children made numerous sacrifices, whether it was forging a formal education, finding work, or remaining hyper vigilant to avoid racism. Though, none of this mattered to the whites who denigrated African Americans for not living up to attainable notions of gender.

Racial discrimination also materialized in the form of large-scale racial violence, and a number of future New York black soldiers and their families were victims. There were countless small-scale instances which, unfortunately, were not always documented. Historians have explored two large-scale race riots that occurred in New York City during the antebellum and Civil War era. The first instance, known as the Amalgamation Riot, took place in 1834 when anti-abolitionists, motivated by rumors of interracial marriages ongoing in the city, violently expressed their displeasure.[13] Even though the rumors were never substantiated, the damage was done as African American and white abolitionists became the targets of violence. And, unfortunately African American New Yorkers received little police protection from the rioters during the chaos. Five future soldiers and their families resided in the city during the chaotic violence. This meant some of the African American men who later enlisted in the Union Army witnessed the chaotic violence of the Amalgamation riot firsthand. Sadly, it would not be their last experience with large-scale racial violence in New York City.

The second instance, known as the New York City Draft Riots, occurred in the summer of 1863 after anti-abolitionists brutally expressed their opposition to the Union’s federal draft, $300 commutation clause, and President Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. When the violence began, rioters initially focused their venom on white Republican strongholds, including the headquarters of the Union League Club of New York. Though, rioters’ violence soon refocused their attention to innocent African American New Yorkers of all ages and genders. By the time the riot ended on July 16, over one hundred African American men, women, and children were dead, and thousands more were severely injured. Numerous homes of black New Yorkers and their institutions, such as the Colored Orphan Asylum, were looted and burned to the ground.[14]

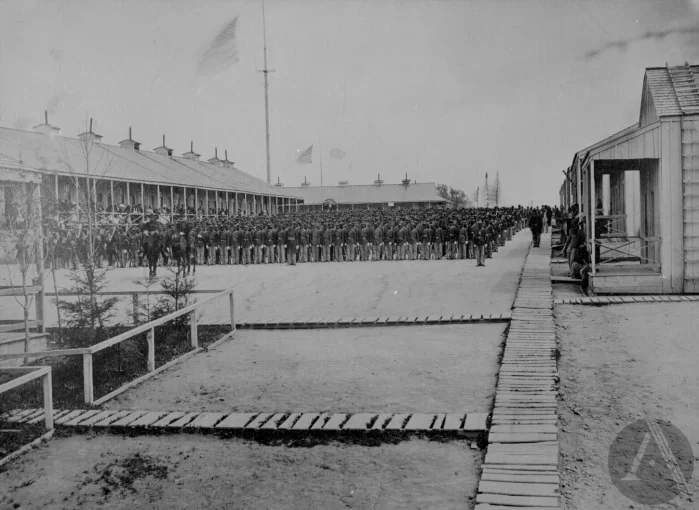

A significant number of black New York soldiers resided in New York City when the draft riot occurred; indeed, fifteen of the men were born in New York City and still lived there in July of 1863. Perhaps the men and their families, of my sample size, witnessed the violence firsthand. For instance, Charles Howard, a future soldier in the Twenty-sixth USCI, and his (unnamed) mother were victims of the racial violence after rioters unexpectedly broke into their home and ransacked their belongings. During the chaos the riots destroyed personal documents, including his birth certificate.[15] Howard never mentioned the details of violence against himself or his mother, but countless other blacks experienced worse situations. For example, Abraham Franklin, who was a handicapped twenty-three year old man, sought to protect an elderly woman from further physical assaults. As a result, Franklin became a victim of a vicious attack that ended with rioters hanging him while his mother watched.[16]When the violence finally ended African American New Yorkers were left to pick up the pieces and make sense of the calamity. And despite their experiences with racial violence, the Twentieth USCI would march down the same streets where black New Yorkers were terrorized and murdered only six months prior.

In closing, the Union’s call to arms effectively removed hundreds of thousands of African American from their homes. Even before the formation of USCT regiments, African American New Yorkers fought a war against racism every day. Military service did not end racism in American society, it only expanded the battleground while placing economic hardships on the families left behind. As a result, the personal safety and economic stability of these working-class Northern African American families continually remained in jeopardy. And it is important that scholars address these lived experiences in places such as New York City in order to see the long-term impact of military service on African American families. After all, it was the families of African American New York soldiers who were left to mourn the dead, struggled to survive economically, and tended to the various disabilities of the veterans after the war. So for these African American New York families, Civil War military service not glorious.

Holly A. Pinheiro, Jr. is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Alabama. He received his PhD from the University of Iowa.

Notes

[1] Gangs of New York. Martin Scorsese. Los Angeles: Miramax, 2002.

[2] Jane Dabel, A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York (New York: New York University Press, 2008), 42, 65-67, 73, 82; Carla L. Peterson, Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 167-171, 261-264.

[3] William Seraile, New York’s Black Regiments During the Civil War (New York: Routledge, 2001), 11-12, 21-27, 31-42.

[4] Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series 2, The Black Military Experience, eds. Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie Rowland (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 12.

[5] Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. Book Records of Volunteer Union Organizations. 20th USCT Infantry, Descriptive Book Companies A-K. PI-17. Vol. 2., RG94. National Archives Records Administration-Washington, D.C. (hereafter NARA-Washington, D.C.); Records of the Adjutant General's Office. Book Records of Volunteer Union Organizations. 26th USCT Infantry, Descriptive Book Companies A-K. Vol. 2 PI-17. RG94. NARA-Washington, D.C.; Records of the Adjutant General's Office. Book Records of Volunteer Union Organizations. 31st USCT Infantry, Descriptive Book Companies A-K. Vol. 2. PI-17. RG94. NARA-Washington, D.C.

[6] Paul Cimbala, Veterans North and South: The Transition from Soldier to Civilian After the American Civil War (Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2015), 104-112; Keith P. Wilson, Campfires of Freedom: The Camp Life of Black Soldiers During the Civil War (Kent, Ohio: Kent University Press, 2002), 59-81.

[7] Jim Downs, Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 18-21, 28-39; Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 48-50, 55-58, 60, 68-69, 72, 77, 80-84, 90-101, 106-109.

[8] Margaret Hope Bacon, Valiant Friend: The Life of Lucretia Mott (New York: Walker and Company, 1980), 140; George M. Frederickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914 (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1971), 147.

[9] Peterson, Black Gotham, 36-37, 44, 113, 123.

[10] Patricia Morton, Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 1991), 8-10; Stephen Kantrowitz, “Fighting Like Men: Civil War Dilemmas of Abolitionists Manhood,” in Battle Scars: Gender and Sexuality in the American Civil War, eds. Catherine Clinton and Nina Silber (Oxford: The University of Oxford Press, 2006), 31-33.

[11] 1865 Claim for Mother’s Pension for Susan Bell; 1865 Mother’s Declaration for Pension in Eugene Bell, Twentieth USCI pension file. NARA-Washington, D.C.; U.S. Census Bureau, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, M653.

[12] Deposition of Sally Mingo, on April 15, 1884; Deposition of George King and William Sterling, on January 17, 1884; Deposition of Ephraim Berrigen, on June 18, 1884, in William Mingo, Twentieth USCI pension file. NARA-Washington, D.C.

[13] Leslie M. Alexander, African or American?: Black Identity and Political Activism in New York, 1784-1861 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011),85-86.

[14] Seraile, New York’s Black Regiments During the Civil War, 13; McKay, The Civil War and New York City, 199-208.

[15] Deposition of Charles Howard, on August 16, 1916, in Charles Howard, Twenty-Sixth USCI pension file. NARA-Washington, D.C.

[16] Report of the Committee of merchants for the relief of colored people, suffering from the late riots in the city of New York (New York: G.A. Whitehorne, printer, 1863), 14.