Stokely Carmichael: The Boy Before Black Power

By Ethan Scott Barnett

Soccer Team, The Bronx Science High School Yearbook, 1960 (courtesy of author)

In the 1960 edition of The Observatory, The Bronx High School of Science’s yearbook, the recently appointed principal Alexander Taffel pronounced to the graduating class a quote from Thomas Paine: “These are the times that try men’s souls.”[1] Paine had recognized the approaching revolution in 1776; the class of 1960 anticipated a similar upheaval. Amongst a sea of young faces in the sports section are two boys - one Black and one white - energetically shaking hands and displaying cheeky smiles. The boys are surrounded by their male teammates and the female management crew. Sports editors Judy Shapiro and Joel Engelstein captioned the image, “Stokely Carmichael and Gene Dennis showed their masterly leadership in preventing the abasement of the opposing teams.”[2] Upon a first and even a second glance this image simply depicts the camaraderie that comes along with teenage boys and secondary school soccer games. However, the image pinpoints a pivotal moment in Stokely Carmichael’s political trajectory. The experiences that led up to this moment concretized Carmichael’s dedication to leftist organizing and a lifelong career in the Black Freedom Struggle.

While much has been written about Stokely Carmichael, his importance as an activist is usually tied to his life after college. Scholars traditionally associate Stokely Carmichael with the Non-Violent Action Group (NAG) in Washington D.C., the birth of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in Alabama, and the famous appeal for “Black Power” in 1966. Scholar Peniel Joseph argues that the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. “gave Carmichael galvanic purpose” while exposing him to the “contradictions, both politically and personally” within the black freedom struggle.[3] Yohuru Williams writes that Carmichael influenced “hundreds of local groups- east and west, north and south” with “the [Black Power] slogan in the summer of 1966.”[4] In The Black Revolution on Campus, Martha Biondi likens Carmichael to Guyanese historian, political activist, and academic Walter Rodney; both were responsible for “bring[ing] ideas of Black Power, popular in the United States, to the Caribbean and West Indian communities in Canada.”[5] While these scholars make important arguments examining Carmichael’s national and even international activism, I’m interested in tracing the origins of Stokely Carmichael/Kwame Ture’s work to his familial lineage, childhood friends, and upbringing in New York.

Roots in the Caribbean

In October 1939, Adolphus Carmichael, his new bride Mabel, along with his mother Cecilia, his three sisters Louise, Elaine, and Olga, and Elaine’s son, Austin settled into their new home in Port of Spain, Trinidad. The house at 42-Steps, which Adolphus had constructed with the help of two business partners, was where Stokely Sandiford Churchill Carmichael was born on June 29th, 1941.

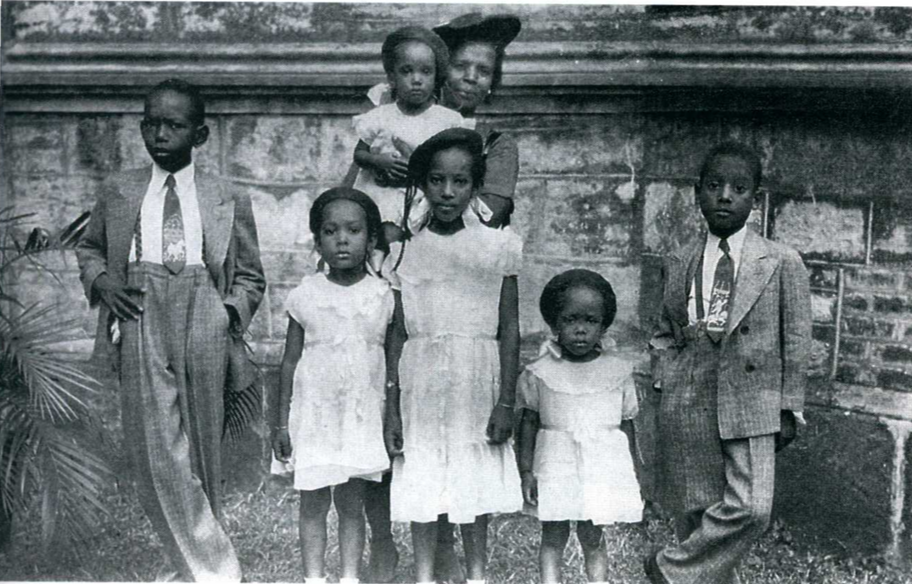

Left: Austin, Aunt Olga holding baby Janeth.

Center Front: Sisters Lynette, Umilta and Judith, Stokely on the Right in Port O’ Spain, Trinidad.

Reproduced from Ready for Revolution.

But tensions in the Carmichael household soon became unbearable; by the time Stokely turned three, Mabel had left for the United States. After repeatedly being challenged by her in-laws, Mabel presented Adolphus with an ultimatum: “it’s me or them; who you choose?”[6]

For Adolphus, the choice wasn’t easy. As the oldest child and only boy in his family, Adolphus had been expected to take on the role of the family provider after his father died. His familial responsibility was compounded by racism; Trinidadians were embedded in the British Empire, facing quotidian repression from colonial rule. Extracting oil, agriculture, and manual labor from the indigenous population had allowed the British to take meticulous control of the island, claiming resources while providing minimal infrastructure.[7] In 1925, there were approximately 290 primary schools on the island and only six secondary schools.[8] This created a few opportunities for formal education. A more realistic path towards financial stability would come from personal connections. Therefore, it’s more likely that Adolphus became a skilled carpenter through an apprenticeship. Nonetheless, he prevailed in acquiring a trade and his network and strengths were valued locally. Adolphus would choose to keep his family intact when possible. Mabel’s decision to leave had been prompted by the security of American citizenship. Adolphus would follow her months later with the intention of bringing the children over right after. Yet, life in New York would prove more complicated than anticipated. Because of racist hiring practices and Adolphus’s informal education, the young couple found it easier to send gifts, money and school supplies to the family, rather than have the family join them.

By the age of four, Stokely had grown fond of the matriarchal household he was born into. Elaine, Olga, and Louise took up variations of familial roles once his parents left. Each had unique characteristics to care for Stokely, his older sister Umilta, and younger sister Lynette. Carmichael remarks that “if grandmother ‘mothered’ me, then it was the strict and exacting Tante Elaine, who, first, in the patriarchal sense of the word, ‘fathered’ me.” Elaine Letren, was a school teacher, disciplinarian and the leader of Adolphus’s sisters. Letren was known for her “proverbial will of iron” that led to a separation from her ex-husband but manifested in a “strong sense of family prerogatives.” Letren’s stern disciplinary action was crucial for Adolphus’s departure to be successful. Within two years of Mabel’s ultimatum, Adolphus risked his “economic place in society” as a stable carpenter with a “growing house-building business” by boarding a northbound fighter vessel to join his wife in New York.[9]

As Stokely grew older his meter to measure injustice budded. His family regularly recounted an election day when Stokely encouraged his aunt Elaine to get to the polls and vote. Although this story may not be entirely accurate, it would be probable that as a young boy Stokely heard tales of Tubal Uriah Butler around the dinner table or read stories about him in the newspapers. Tubal Uriah "Buzz" Butler, was a Grenadian-born Spiritual Baptist preacher and labor leader in Trinidad and Tobago. In September of 1956, the New York Age deemed him a “demagogic union leader,” but in 1948 a 7-year-old Stokely considered Butler the ideal candidate to vote for. On the day of the election, the child urged his aunt Elaine to vote for “Mr. Butler” because “he went to jail for us, now he can do even more for us.” When his aunt refused, he “dressed himself up in the suit with the big lapels that his parents had sent him from New York…marched his little self right down to the polling station.” Upon arrival an officer told him “you have to wait until you are twenty-one” and Carmichael ended up “racing home in tears.”[10] This anecdotal story of political engagement became family legend. Carmichael himself claims that he did not make the “connection between Mr. Butler’s mass demonstrations and my barefoot hungry schoolmates,” but it does allude to Carmichael’s reception to emotional, social and political injustice.[11] Aunt Elaine recalls that it wasn’t just electoral politics that prompted Stokely’s earliest inclinations to fight for people’s needs. He remembers hiding “food in a butter can to take to a classmate who only ate crackers at lunchtime” and was persecuted by Elaine for “keeping company with some barefoot, scruffy little boys” after church one afternoon.[12] Indeed, Stokely was a deeply empathic boy, some of which was easily a product of his loving home and religious upbringing; the rest may have been a natural response to childhood incorruptibility.

New York, New York

Adolphus Carmichael and Mabel (Charles) Carmichael at the beach in New York City - 1950s. (Reproduced from Ready for Revolution)

When Stokely’s grandmother Cecilia Harris Carmichael died on January 16, 1952, his life changed drastically. It had been six years since his father had left and eight since his mother gave her husband the ultimatum. Stokely and his siblings were to be reunited with their parents and youngest sibling for the first time:

“I recognized my sisters born in America; they had visited us in Trinidad. Soon my mother was hugging all three of us at the same time, with little Janeth and Judith squeezing in just a-squealing and a-hugging whatever they could reach, knees, bellies, whatever. There was laughing, crying, hugging, and everyone talking at the same time. Kisses flew around the group indiscriminately. Passing travelers turned their heads and smiled indulgently as they went by. Those Africans certainly are an expressive people.”

– Stokely Carmichael, on reuniting with his family in New York in June 1952 [13]

When the Carmichael family arrived at the pre-war apartment building at 861 Stebbins Avenue in the Bronx, they were one of the many families moving to New York in search of the American Dream. Waves of immigrants from the West Indies utilized family networks to bring kin over. The journey required strategic planning, often taking years, as it had for the Carmichaels. Despite the obstacles, America “represented different kinds of opportunities for the Caribbean immigrant” that rarely materialized in the Caribbean and Latin America.[14] Consequently, when Stokely and his sisters arrived at their new building he quixotically asked his parents, “this whole big house is for us?” only to be met with “no son…lots of families live here. We just have an apartment.” [15] Any fantasies that Stokely had about the prospects for American opulence were quickly put into perspective. New York was not only chock full of immigrants from the Caribbean but was also in the midst of receiving an influx of migrants from the American South and Puerto Rico, a shift that would transform the postwar city

A few years after Stokely’s arrival in New York, Adolphus purchased a two-story single-family home at 1810 Amethyst Street in the predominantly-Italian Van Nest neighborhood. What first appeared to be a snafu in the cultural and systematic procedure that sought to keep Black families out of white neighborhoods became more apparent as Carmichael recognized his father purchased an “absolute dump.”[16] Nevertheless, for a skilled and imaginative carpenter as that of Adolphus, this home was a “dream” project. Neighbors relinquished their skepticism over time as the home at 1810 Amethyst Street transformed from an “eyesore” into “one of the more attractive and well-maintained” homes on the block. For working-class Italians, there was no better way to gain approval than the dedication it takes to renovate a house.[17]

Carmichael’s New York was unique not just because he was an immigrant, but because he had grown up in a world where Black people received ample educational opportunities. Stokely recalled his surprise after moving to New York City at 11, “not only could I compete academically, but that I was actually much better prepared than the American kids.”[18] In New York, Blacks and Puerto Ricans had been gerrymandered into exceedingly segregated schools that were overcrowded, underfunded and occupied by lackluster teachers. At P.S. 39, Stokely’s first middle school in the Bronx, the classroom was “so noisy, so disrespectful, so destructive” that he almost had a nervous breakdown.[19] Most shocking to the young scholar was the difficulty the teacher had controlling the classroom; screaming out “Gosh darn it, settle down” after multiple failed attempts at restoring order.

In 1956, Stokely was admitted to the prestigious Bronx Science High School. Carmichael argues that he was accepted on “intellectual merit, untainted by any suggestion of demanding ‘racial’ preference.”[20] In the same breath, however, the complexity of the situation is apparent: “I have no illusion that me being their sole African student didn’t have something to do with the middle school’s [P.S. 83] decision to nominate me. Or that Bronx Science did not understand clearly that they had to make room for at least a few Africans or risk being denounced for racism by the African community. Even in 1956, we had a word for it. We called it tokenism.” Carmichael and the 10 visibly Black students in The Observatory represent the evolving dialogue around school integration. The reality was that Black and Brown communities in New York were regularly fighting for equal education. By 1957, organizations supporting integration had persuaded the Board of Education to conduct a “mass transfer” of teachers to combat unequal education conditions. The New York Times reported that it’s “difficult to get regularly appointed teachers to take assignments in Harlem and other areas with a preponderance of Negroes or Puerto Ricans” because the schools create “difficult if not impossible situations.” to teach in.[21] Activist and eventual mentor to Carmichael Ella Baker led a campaign against the New York City Board of Education and white organizations for providing inadequate education to African American and Puerto Rican Students in the 1940-50s. Backed by the Harlem branch of the NAACP and New York Urban League, Baker was recognized all across the city for her steadfast activism and willingness to take on the biggest stalwarts in local politics.[22] The teacher transfer would be brought to a halt by the groups of white parents and teachers who were determined to keep things as they were. No matter the circumstances, Carmichael felt he was interacting with some of the sharpest minds in the city. One of his first memories took place during attendance. Each student stated their name and what books they read over the summer. As Carmichael recalls,

“A boy sitting immediately behind me claimed to be reading Capital by Karl Marx. Long before they got to me, my hand was down for I was scribbling furiously, writing down all these unknown writers who I would read as quickly as possible for I resolved I had known whatever my classmates knew. I ended up with quite a reading list that first day.”[23]

That “boy” was Eugene Dennis Jr., known as Gene. Gene was the son of Peggy Dennis and Eugene Dennis Sr. Peggy was born Regina Karasick in Los Angeles, California to a family of staunch Russian-Jewish Socialists. She started attending Jewish emigres meetings at the age of 4 and had grown up with her family reading the Forverts (Forward) and Freiheit (Freedom) to one another around the dinner table. By 16, Peggy was a key member of the Young Communist League’s (YCL) connective tissue, organizing over 300 children into weekly groups by age and location. She worked on creating a curriculum to “expand the children’s horizon” and allow them to immerse themselves in the revolutionary struggle through music, performance, and games.[24]

Eugene Sr was born Francis Xavier Waldron on August 10, 1905, in Seattle, Washington. Born into a family of labor coordinators, Waldron was eager to organize the growing workforce in Seattle where his father was apart of the Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World) Union. In 1926, Waldron joined the American Communist Party. By 1929 he had met and married Peggy, been arrested several times, changed his name, and moved to the Soviet Union, where he remained until 1935. In 1942, Eugene Jr. was born in New York. At the time his father was the General Secretary of the American Communist Party. In Child of the Left, a documentary about family, politics and the communist movement in Cold War America directed by Fred Simon, Gene recalls his parents’ political involvement from a child's perspective:

“From perhaps of the age of 5 or 6 the May Day marches, parades, standing next to my father at the communist rallies. To be in the environment was very enabling to begin to test out what path I wanted to take intellectually, philosophically and perhaps even organizationally.” [25]

By the time Gene and Stokely met as freshman at Bronx Science High School, Dennis Sr. had been imprisoned twice, most recently for violating the Smith Act. Carmichael remembers “liking this kid instinctively…He was a good student, serious and smart. But he was funny and irreverent, friendly and natural. He was comfortable and easy to be around, unlike some of my other white classmates.”[26] Gene and Stokely would create a bond that could not be broken.

Beyond his relationship with Gene, Stokely also entered into the political orbit of the Dennis family. Being invited to Gene’s home provided Stokely with opportunities to meet socialist organizer Bayard Rustin on multiple occasions. Peggy was regularly writing articles for Political Affairs and the Daily Worker on women’s issues in the Communist Party alongside Trinidadian revolutionary Claudia Jones.

On a more quotidian level, Gene’s friendship allowed Stokely the opportunity to escape his strict family and explore Harlem. Carmichael was used to seeing Queen Mother Moore on the street corner and stopping in at Michaux’s bookstore where he first encountered George Padmore’s Pan-Africanism or Communism. The nature of the Dennises’ politics introduced Stokely to “a cultural synthesis” of leftist groups within the Black mecca of Harlem.[27]

Not all the students at Bronx Science were as accepting of the Dennis family; Stokely remembers that “an Italian classmate approached me belligerently” demanding to know “why are you always hanging with that blank, blank, expletive, blank Communist Gene Dennis?” The Italian classmate’s remark embodies the opinion of a considerable number of Americans at the time. McCarthyism was burning all threads of communism into dust. Americans were forced to decide between the capitalist West and the Communist East. The latter was regularly depicted as the ultimate evil, and anyone associated with the ideology or organization should be disciplined for Un-American activities. Artist, musician, and organizer Paul Robeson once consoled Gene Jr. as a child. Weeks before his father went to jail, [Robeson] “called me and took me on his lap…it chokes me up every time because I can remember during that scary time…and I can remember him singing to me and I was safe… I was safe.”[28]

Dennis and Carmichael’s friendship provided great intellectual and emotional stimulation that both would continue to seek out in college. Through Gene, Carmichael was regularly introduced to texts, people and ideas that few were questioning. In Stokely, Gene had a friend that accepted him as he was, allowing him to escape the monumental stress of being surveilled by the United States government. In their junior year, Carmichael and Dennis ventured to Washington D.C. to join a group of organizers protesting the House Un-American Activities Committee. It was while there that Carmichael met a group of Black activists from Howard University that were affiliated with SNCC. Their group, the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG) was just what Stokely was missing in his life. The experience would be so transformative that Carmichael deciding then that he would attend Howard University upon graduation.

It is impossible to know where Stokely Carmichael would have ended up did he not attend The Bronx High School of Science. However, like many revolutionaries before him, New York was many things for Carmichael. First and foremost it was the place where Stokely reunited with his family, joining the thousands of migrants from the West Indies and United States South in looking for new opportunities. Secondly, the city provided Carmichael with a state of the art education in revolutionary thinking and acting. The streets of Harlem granted him with a one-of-a-kind lecture series that money couldn’t buy. Lastly, the homes of his classmates and family nurtured his commitment to radical politics and desire for genuine human connection.

Ethan Scott Barnett is a filmmaker, cultural worker and Ph.D. student in History at the University of Delaware.

Notes

[1] Observatory, Bronx Science High School, 1960, 2.

[2] Ibid, 19.

[3] Joseph, Peniel E. Stokely: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas, 2016., 255.

[4] Williams, Yohuru. "Introduction." Liberated Territory: Untold Local Perspectives on the Black Panther Party, 2008, 1-31. doi:10.1215/9780822389422-001.

[5] Biondi, Martha. The Black Revolution on Campus. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014, 12.

[6] Ibid, 20.

[7] Neptune, Harvey R. Caliban and the Yankees: Trinidad and the United States Occupation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007, 36.

[8] "Historical Development of Education in Trinidad and Tobago." UFDC Home - All Collection Groups. Accessed April 24, 2019. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00010880/00001/8j.

[9] Carmichael, Stokely, and Ekwueme Michael Thelwell. Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), New York: Scribner, 2005. 21.

[10] Ibid, 33.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Carmichael and Thelwell. Ready for Revolution, 31.

[13] Ibid, 48.

[14] Watkins-Owens, Irma. Blood Relations,18.

[15] Carmichael and Thelwell. Ready for Revolution, 48.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Carmichael and Thelwell. Ready for Revolution, 70.

[18] Carmichael and Thelwell, 62.

[19] Carmichael and Thelwell, 56.

[20] Carmichael and Thelwell, 73.

[21] NYT “Teachers Attach ‘Draft’ Proposal, February 2nd, 1957 https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1957/02/07/87214367.pdf

[22] “Who’s Who in Local Politics: Ella Baker is a Champ Fund-Raiser for Local Causes,” New York Age, July 24th, 1954, 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/40689946

[23] Ibid, 85.

[24] Kaplan, Judy. Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1998,18.

[25] Child of the Left. Directed by Fred Simon.

[26] Carmichael and Thelwell, 90.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Child of the Left. Directed by Fred Simon.