Remembering the Columbia Protest of '68: Students

Fifty years ago this week, students at Columbia shut down the university for seven days, in protest of plans to build a gymnasium in a nearby Harlem park, university links to the Vietnam War, and what they saw as Columbia’s generally unresponsive attitude to student concerns.

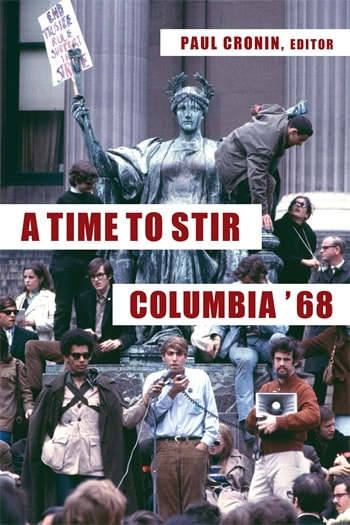

Today on Gotham, we begin a weeklong series featuring excerpts from a new collection of more than sixty essays, edited by Paul Cronin, reflecting on that moment. A Time to Stir reveals clearly the lingering passion and idealism of many strikers. But it also speaks to the complicated legacy of the uprising. If, for some, the events inspired a lifelong dedication to social causes, for others they signaled the beginning of a chaos that would soon engulf the left. Taken together, these reflections move beyond the standard account, presenting a more nuanced Rashoman-like portrait. We begin today with the remembrances of students (male, female, black, white, visiting, resident, pro, anti), carrying forward the approach with faculty, police officers, government servants, and "outside agitators," every day the rest of this week.

Philip Lopate

Much as I shy away from the very notion of generational identity, I must own to being a creature of the sixties. Born in 1943, I entered Columbia as an undergraduate in 1960, graduated in 1964, and was influenced unsystematically by that period’s anti-Establishment attitudes. The sixties have been so mocked, caricatured, or flattered by later generations that anyone who lived through that era sometimes seemed to have had only two choices: loyal defender or turncoat. What often is missing, which I would like to propose, is a middle path: critiquing our mistakes and misconceptions while remaining sympathetic to the era’s spirit of idealism and experimentation...

Having graduated four years earlier from Columbia College, I was drawn to the student rebellion for several reasons: (1) opposed as I was to the Vietnam War, I had been participating in marches in New York and Washington, D.C., distributing flyers to unsuspecting pedestrians, and generally answering the call; (2) having spent several years in writerly isolation, I was looking for excitement, communal and erotic (file under: “the personal is political”), and (3) I envied the students their fun. The Columbia I had gone to at the beginning of the sixties was a staid, tweedy place. We had aspired or pretended to be sober, mature grownups, and in consequence, I felt I was missing out on my youth. As a late-comer to the bacchanal, I wanted to protest and to party.

I visited the first floor of the student center at Ferris Booth Hall (since torn down), which had been taken over as strike headquarters. Before we could enter, we had to be vetted by somber student guards wearing Che berets. I was immediately struck by the theatrical mise-en-scène of it, the air of dress-up, a militancy pastiche thrown together from Ho Chi Minh’s North Vietnam, Fidel’s Cuba, and Mao’s China. Card tables carrying pamphlets, posters, radical literature, buttons, and other revolutionary paraphernalia lined the room. The atmosphere was, despite a certain grim determination—the frustrated feelings that something had to be done about the war, that we had to act, not simply stand by—like a street fair.

A few days later, I was given a tour of Fayerweather and Avery, two of the occupied buildings, and I saw the dishabille of sleeping bags and blankets, book bags, and portable typewriters. It looked like a pajama party, it looked jolly, with the exception of interminable meetings at which everyone who wanted to speak could. Direct democracy notwithstanding, I already had been tipped off that the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) leaders would manipulate the outcome by holding off votes until early morning, when they could be assured a majority. Still, I was impressed with the practical arrangements being made for daily operations, food delivery, and chores. It did not occur to me to join the occupying students, especially with my apartment’s warm bed close by. It was enough just to have seen the sleep-ins to feel part of history in the making.

Much was made later of the cavalier way the students mistreated university property, smoking the president’s cigars and turning hallowed classrooms into messy dorm pads. Certainly, some hostility was being expressed toward this institution of higher learning; but the occupations also may have signified an affection for the university, or a longing to know it with greater intimacy, by snoozing on its floorboards. I understood this ambivalence, having, on the one hand, fallen in love with Columbia, ever grateful for the fine education it had given me, and on the other hand, put off by its chilly impersonality and clubby exclusions...

The college was still all male, and the hottest political issue at the time was whether women should be allowed to visit the dorms. (I was all for it.) The paternalistic, in loco parentis attitude on the part of the university administration rankled deeply. The fact that then-president of Columbia, Grayson Kirk, was known to be resistant to women faculty only intensified our opposition to this patriarchal authority figure. You could never admit aloud that the students’ rebellion was partly Oedipal, but you could think it. And so what if it was?

I received notice that some graduates were forming an organization in support of the student protests, but I went to the first meeting. Out of it came Alumni for a New Columbia (ALFONECO). We fancied ourselves the progressive, pro-youth alternative to the official, conservative alumni association, which supported President Kirk and the antiprotest students to the hilt. As with many New Left organizations, our members ran the gamut from mildly liberal to revolutionary, a confusion which would have to be sorted out later. For the moment, we were united by goodwill toward the strikers and a desire to support them. My own political position at the time might be best defined as social democratic, more in sympathy with Sweden’s social welfare state than Maoist China, but I felt guilty about my wishy-washy politics and was open to persuasion by the more militant stance of the SDS radicals who were spearheading the unrest, should historical events move in a more extreme direction. Tom Hayden, who had helped found SDS in 1962, remembered the chairman of Columbia SDS, Mark Rudd, as “absolutely committed to an impossible yet galvanizing dream: that of transforming the entire student movement, through this particular student revolt, into a successful effort to bring down the system.”1 It’s hard to credit now the gullible belief that such an overthrow of the government and the whole capitalist system was even in the offing. I remember going during this time to a reading at St. Mark’s Church, and the poet Anne Waldman whispering in my ear: the word on the street was that it was going down this summer. “It” being the revolution. I very much doubted that, but was intrigued that there even existed rumors about the possibility...

But looking back, I wonder how much I actually accepted the logic of the strike demands. For instance, one of the chief demands was that the university sever its ties from the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA). Although Columbia initially had been an institutional sponsor of IDA, the university had no outstanding contracts to do military research at the time of the Columbia protests. Some individual faculty members did have dealings with the government, but the traffic was minimal: IDA served more as a conveniently symbolic focus for student outrage against the Vietnam War than an actual player on campus. Of course, in a larger sense, the university was thoroughly integrated into the “military-industrial complex,” as Columbia’s former president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had termed it: how could it not be? SDS researchers were busy charting the overlapping elite who sat on the boards of banks, corporations, newspapers, government agencies, and universities. Was this a genuine conspiracy or the logical outgrowth of a corporate society?

As for the gymnasium that Columbia had wanted to build in nearby Morningside Park, in retrospect it might not have been such a bad thing; the park was a shabby, neglected amenity that could have used some traffic. The bulk of the building would have been allocated to the university, while a smaller section with a separate entrance, occupying some miniscule percent of square footage, would have served the community. That the entrance to this proposed community facility was located below, in the park, had unfortunate connotations of a tradesmen’s or servants’ entrance, which the protesters fastened upon, although the reason for that arrangement had more to do with topography than racial prejudice. The Harlem community leaders, originally in support of the gym, had grown mistrustful, rightfully suspicious of a Columbia land grab. The university has had a long history as an acquisitive neighbor: witness its recent expansion into Manhattanville. Still, the upside was that the community would have gotten much needed recreational facilities, including a swimming pool. But its elected officials, State Sen. Basil Paterson and Assemblyman Charles Rangel, had both come out against the gym construction, while firebrand H. Rap Brown had said if it were built it should be torched to the ground. In essence, the strikers’ demand to stop the gym’s construction was largely symbolic, a way for SDS to link the antiwar protest to civil rights and to defer to the black students who were occupying Hamilton Hall and who themselves were deferring to the Harlem community

Columbia, having spent millions on preliminary planning for the gymnasium in Morningside Park, gave it up, severed its formal connection with IDA, and suspended punishment for almost all student infractions. The criminal cases against the arrested students also were dropped. So in that sense, perhaps the demands were shrewdly conceived as practical and achievable, and their having been met in the end constituted a victory for the strike. Conversely, because they were largely symbolic, their accomplishment changed little of substance. The faculty had taken the demands quite seriously, and tried to negotiate on each item to bring about a peaceful resolution, using their (excessive) faith in the powers of reason to avoid a police bust. The student protest leaders did not, I think, take the demands as seriously. Mark Rudd himself later boasted to a reporter that “we [SDS] manufactured the issues. The Institute for Defense Analyses is nothing at Columbia. Just three professors.... And the gym is bull. It doesn’t mean anything to anybody.”

But whether or not the demands were serious, SDS dug in, refusing to compromise on them, so as to compel exactly the theatrical, bloody denouement that occurred when police ousted the students. It was this very outcome the professors acting as go-betweens had dreaded... the faculty cared more about protecting the students from physical harm than the students themselves did.

Youth believes itself immortal; those who have attained middle-age know otherwise.

Phillip Lopate has written more than a dozen books, and edited several anthologies. He is a professor and former director of nonfiction in the Columbia University graduate writing program.

William W. Sales Jr.

The Columbia insurgency occurred within the opening decades of the postindustrial period. Major universities like Columbia were in the forefront of adopting a corporate-business as opposed to a collegiate model of structure and administration. By the late sixties, behind a facade of being an oasis of thought and free expression, Columbia had become an important component of the war-making and urban renewal machinery of contemporary America. This metamorphosis was not unchallenged inside of Columbia, but increasingly, the administration and the board of trustees were unresponsive to those students and faculty who feared that the institution was coming up on the wrong side of the struggle for human rights and social justice.

Columbia students were changing as well, and especially its black students. In the mid-sixties, the class character of the majority of black undergraduates shifted from the upper levels of a prep-school-educated black bourgeoisie to a more unequivocal background in the working class and the public school system. When we got to Columbia, most of us were laboring over a false dichotomy, which characterized the “house Negro” understanding of white people. According to this schema, there were “good” white people and “bad” white people. “Good” white people were middle-class whites who were in the professions or business and employed black servants as part of their lifestyle. They were viewed by many blacks as kindly, generous with their gifts, and protective of their servants over and against the depredations of “bad” whites. The latter were white lower-class bigots prone to mediate their relations with black folks through gratuitous and copious racist violence. Knowing how to act around “good” whites (cultural assimilation) and avoiding those places habituated by lower-class bigots was the key to successfully negotiating the racial divide in America. Education became the key to salvation, as it was the most rapid venue for racial and cultural assimilation. This was seen as especially true at private, elite, Ivy League institutions like Columbia...

For many of us, Columbia turned out to be a bitter disappointment. We saw the university as a community of “good” elite white folks and assumed we were safe from racial bigots there. We were wrong, for some of the “good” white folks were as bigoted as their poorer counterparts. Those who were not personally racial bigots supported policies of institutional racism that did harm to black folks and people of color.... Thus, we increasingly were alienated from Columbia. This alienation, however, led us to search for a more satisfying mission to promote human rights and social change. An older group of conservative black student assimilationists and gradualists were nervous about challenging the racial status quo on campus. These two groups struggled for influence and leadership within the Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS), with the conservatives winning out initially over a more activist minority. The essence of that conflict was encapsulated in a debate that took place in March 1969 in the pages of the campus student newspaper Spectator, between black conservative Oliver Henry and me as a spokesperson for movement activism. This internecine struggle was largely limited to undergraduate black students, until the 1968 takeovers, which initiated a dynamic that transformed the conservatives represented by Henry’s position from a majority of black students to a distinct minority...

In much of the literature on the Columbia protest of 1968, organized black students in Hamilton Hall are identified as SAS. This is inaccurate. SAS as a body never endorsed participation in the takeover. Members of SAS certainly were present... but so were other significant organizations of black Columbia and Barnard students. To highlight the breadth of our support among that black student community, our press releases and other material we issued while in the buildings used the phrase the “Black Students of Hamilton Hall,” which quickly morphed into “Black Students in Nat Turner Hall of Malcolm X Liberation University.” We discussed in our earliest meetings in Hamilton Hall how we should identify ourselves. We knew a conservative bloc within SAS would not endorse cooperation with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), let alone a building takeover. Given the lack of an organizational meeting and the experience of decision-making within the organization on controversial issues, we picked a name that reflected the reality on the ground.

White students were also changing. White participation in the civil rights movement had created a space for the children of the Old Left to find their own radical roots in a New Left insurgency. Especially through participation in Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) or in support of its white student activists, white radical students became more critical of the American status quo of the fifties and early sixties. SDS represented the cutting edge of this new white militancy, but it was apparent to some degree in large numbers of white students. This radicalization accelerated with increasing US involvement in Vietnam. As with all wars, Vietnam had become not only a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight but also an old man’s war and a young man’s fight.

Increasingly, black students could find allies within the white student body. This alliance was not formed easily, however. Black students had been immersed in the anti-Communism of the postwar period. Our radical leadership—W. E. B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, and Claudia Jones—had been decimated by the impact of McCarthyism. Non-Communist but progressive black leadership also had been redbaited and stigmatized. The Federal Bureau of Investigation had put both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X on the Security Index because of their alleged Communism or Communist affiliations. There persisted in American society the feeling that black people who challenged the racial status quo were either Communist dupes or Communist themselves. The New Left orientation of SDS clashed with the feeling among black students that we should avoid being perceived as Reds. At the same time there was a debate within the Black Freedom movement on the role of the Communist Party USA and Old Left Communism in our struggle. Writers like Harold Cruse accused the party of elitism and paternalism in its relations to its black members. In the behavior of white radical student leaders, there was enough elitism and paternalism to support these black misgivings. These white leaders tended to dismiss our misgivings about using extreme Left rhetoric in media interviews and broader community forums. On our part, we always emphasized our relationship to local black struggles in language already prevalent in our struggle. We called for a new relationship between Columbia and the community, not the overthrow of capitalism. To the extent that SDS leadership was committed to this stance, it created difficulties in establishing and maintaining an alliance with black students as it opened our leadership up to the claim that we were mere dupes of whites who were not really committed to black liberation....

Black students in Hamilton Hall did not “split” with the agenda of white students. We endorsed the demands of the strike and never wavered from that position. There were, however, important tactical considerations that could not be ignored. We felt that white students underestimated the violence that the system was capable of directing at its own citizens when challenged. Black students knew this from the beginning. As a small minority of the student body, blacks did not want mere numbers to swallow up their presence in the demonstration. In addition, our smaller numbers and stronger mutual familiarity allowed us to arrive at firm consensus significantly quicker than our white counterparts. Stylistically, the ultrademocracy of SDS with the amorphous, fluctuating white membership in the strike was a protest style we wanted no part of. It appeared to us anarchic. I personally respected the SDS leadership. The need to keep cohesion among their constituency was a monumental task that they should be praised for executing. Their self-sacrifice and adherence to a principled position in support of oppressed people of color, in Harlem as well as Vietnam, commanded our respect. No decision to assume separate tactical headquarters should imply that we were not comrades in the same fight. The occupation of Hamilton Hall was a spontaneous action, but the black student activists were by then networked with each other and with numerous leaders and resources within the Black Freedom movement. This is true even with the acknowledgment that the majority of black Columbia students had not participated previously in a major civil rights protest. The richness of these previously solidified human and organizational resources was a major reason we succeeded in Hamilton Hall.

William W. Sales, Jr. is a professor emeritus and past chairperson of the Department of Africana Studies and director of the Center for African American Studies at Seton Hall University.

Carolyn Rusti Eisenberg

Gender was a huge problem, both before and during the Columbia strike. To say that the atmosphere was macho is akin to saying it’s warm on the Equator. A group of twenty-year-old white men, many of them close friends, paralyzing an entire university in New York—the media capital of the world—was an electrifying experience. It didn’t help matters that during the first night of the occupation, the young black men from Columbia’s Students’ Afro-American Society had thrown them out of Hamilton Hall, with the invidious comparison that “we are prepared to die here and you are not.” It was a stinging reproach, which never ceased to fester, creating an additional impetus for male assertiveness on the steering committee.

Meanwhile, television and newspapers magnified the drama. With each passing day, they drew an ominous picture of the occupation at Columbia as a revolutionary event, and its long-haired perpetrators as the local equivalents of Fidel and Che. Some of this was plainly ridiculous. I remember sitting in meetings and somebody would come in and say, “Mark, it’s your mother again! You’d better take it.” And sure enough, the revolutionary leader would rush dutifully to the phone, while we all waited patiently until he returned and the conversation could proceed.

But the media coverage was heady stuff and fostered a certain conviction in the steering committee that here at Columbia we really were setting a revolutionary example, that we weren’t simply challenging certain university policies, but rather the legitimacy of the institution and of society as a whole. Moreover, in making strategic decisions about next steps, our job was not to represent the people in our buildings, but rather to function as a cadre, prodding people to new levels of militancy. Everyone had apparently read Régis Debray, the revolutionary who had articulated this point of view with particular force and clarity.

We were very young then. But the beards and long hair notwithstanding, we were youthful patriots, watching our country devastate another society. And in 1968, most grownups seemed quiescent or even complicit in the damage. By then, it no longer seemed adequate to go on being our regular selves, but it was hard to find a different identity that was adequate to the challenge. Faced with such carnage, some imagined themselves Third World revolutionaries, whereas others invested fresh hope in the power of a peaceful community. Yet in that year, the killing went on and nothing seemed to work. One striking aspect of my Vietnam travels [many years later] was meeting contemporaries from that nation, whose lives had been upended by the conflict... the friendliness was overwhelming. The reasons were similar: “We knew Americans were protesting! It meant so much to us to know we weren’t alone! It gave us hope!”

Against this backdrop, I found myself in Vietnam writing to Mark Rudd [while researching a book in 2009]. He had long ago morphed into a warm and thoughtful adult and the hatchet was buried. But the deeper questions were generational and not personal: How do we understand the bitter quarrels of that time? What mistakes were made? What did we accomplish? And perhaps most pertinent in today’s militarized country: What should be our contribution to a more peaceful future?

Carolyn Rusti Eisenberg is a professor of U.S. foreign policy at Hofstra University.

Michael Neumann

The 1968 Columbia “student revolt” doesn’t rate as history. What matters about it is why it fails to do so. 1968 marks the year when the American Left ceased to matter. The reason is simple: the Left moved from addressing real issues to hyping fake causes. The causes were fake because they either were unformed and hysterically grandiose—“smash imperialism”—or tiny, yet purportedly fraught with significance, like Columbia University’s development plans for the neighborhood.

Just what was fake about these causes? Whether grandiose or absurdly modest, they offered no realistic prospect of social or political change. This doesn’t mean the ’68 radicals were irrational, or that rationality is essential for good politics. Successful, valuable political movements haven’t always had some elaborate ideology and they haven’t always followed reason more than instinct. Besides, the most fake-extreme of sixties radicals always had some ponderously rational “theory” stashed away somewhere, built on whatever assumptions pleased them. What I mean by a “fake cause” is “no cause at all,” no attempt to achieve anything—only a successful attempt to feel like an achiever.

The fakery comes out in high relief against the background of the times. The hippie movement was large and real; the lifestyle changes left their mark. The antiwar movement, too, was large and real. Wives of navy officers looked for antiwar speakers and someone wrote to the San Diego Union: my son just died in Vietnam and I want to say that he did die in vain. There was a real surge of social and political opposition. Its misfortune was that it came a bit later than the student Left, which therefore was awarded a kind of leadership of the whole show.

In 1968, the student movement abandoned the antiwar cause, and so, of course, the Vietnamese people. There was no more talk of actions that made any effort, no matter how small, to actually affect the prosecution of the war: no plans to stop troop trains, to disrupt the draft, or to agitate within America’s armed forces. The student Left had acquired another interest: therapy through “radicalism.” It sought cosmetically extreme actions as a means of transcending its middle-class hang-ups. Students became fighters—“warriors” they would be called today. They felt braver, purer, cooler. This was an end, not some means to some end; indeed, it confined itself to efforts ostensibly aimed at ends never on the horizon. It “demanded” not the sort of cultural change that hippies went some distance to effect, but a profound, deeply radical and structural transformation of society erected on the thorough destruction of the Western political and social order.

Some will tell you this was an ideal, a wild dream, a courageous and noble enterprise. There’s nothing wrong with ideals and wild dreams; sometimes they have helped to sustain successful political movements. But the oracular rhetoric of the ’68 radicals doesn’t strike me as the innocent expression of an ideal. I believed, and still believe, it was a massive outpouring of bad faith and, despite itself, it was quintessentially American.

Michael Neumann was a founding member of Columbia Students for a Democratic Society. His books include What’s Left? Radical Politics and the Radical Psyche.

—

Copyright (c) 2018 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.