Pioneras Boricua

By Cathy Cabrera-Figueroa

Puerto Ricans who migrated to the United States in the early 20th century were not the first to do so. Trade and commerce linked Puerto Rico and the United States before the 19th century and movement between the two has continued since then.[1] However, “between 1920 and 1940, the Puerto Rican population in the States grew from fewer than 12,000 to almost 70,000.”[2]

Piecing together the migration stories of Puerto Rican women who came to New York City after the Great War is quite challenging. These women were regular people, and until the 1960s and 1970s, there was little incentive to collect or archive their experiences.[3] Using oral histories collected in the second half of the 20th century can help us piece together who these Puerto Rican women who migrated to New York City before the 1940s were, how they got here, why the migrated, and the obstacles and challenges they experience once they arrived.

“The story hour candle was lit, the name of the story introduced, and the story began.”[4]

Liga Puertorriqueña de Brooklyn (Puerto Rican League of Brooklyn) 1922.

Librarian Pura Belpré began her story hours by lighting a candle, placing flowers on the table, and having a story ready to tell. Belpré was part of the first large wave of Puerto Ricans who migrated to the United States in the 1920s. She arrived in 1921 and settled in New York City, where Puerto Rican communities had begun to develop in the 1920s with the proliferation of Puerto Rican-owned businesses including bodegas, barberías, botánicas, restaurants, boarding houses, and storefront churches, as well as legal and medical offices.[5] Records indicate that the number of Puerto Ricans in New York City increased from 7,364 in 1920 to 44,908 by 1930.[6] Puerto Ricans arrived in New York City in search of employment, housing, education, and health care for themselves and their families.

As the first Puerto Rican librarian in the New York Public Library system, Belpré took great pride in recounting the folktales she heard as a child growing up in Puerto Rico to recent Puerto Rican migrant families who visited the library. She also became the first Boricua to have these folktales published in English. Most of what we know about Belpré is based on personal interviews, interviews with colleagues and friends, and her correspondence and essays. Arguably, for many Puerto Ricans in New York City, she is a pioneer.

In comparison to other women who came to the United States during those decades, there is more information available about Belpré because she was well-known and kept in contact with fellow librarians, publishers, schools, and organizations where she did her storytelling. Her career as a librarian and published author stands in contrast with that of other Puerto Rican migrants who, due to financial and familial obligations, were often unable to pursue a formal education and professional career. Friends and colleagues described her as a generous and gregarious woman who was reserved when it came to discussing her private life.[7] With all we know of Belpré from her extensive archives, we still do not know all we could about her. How much more difficult is it to construct the migration stories of unknown Puerto Rican women migrants?

“And like that man who came to dinner, we never went back to Puerto Rico.”[8]

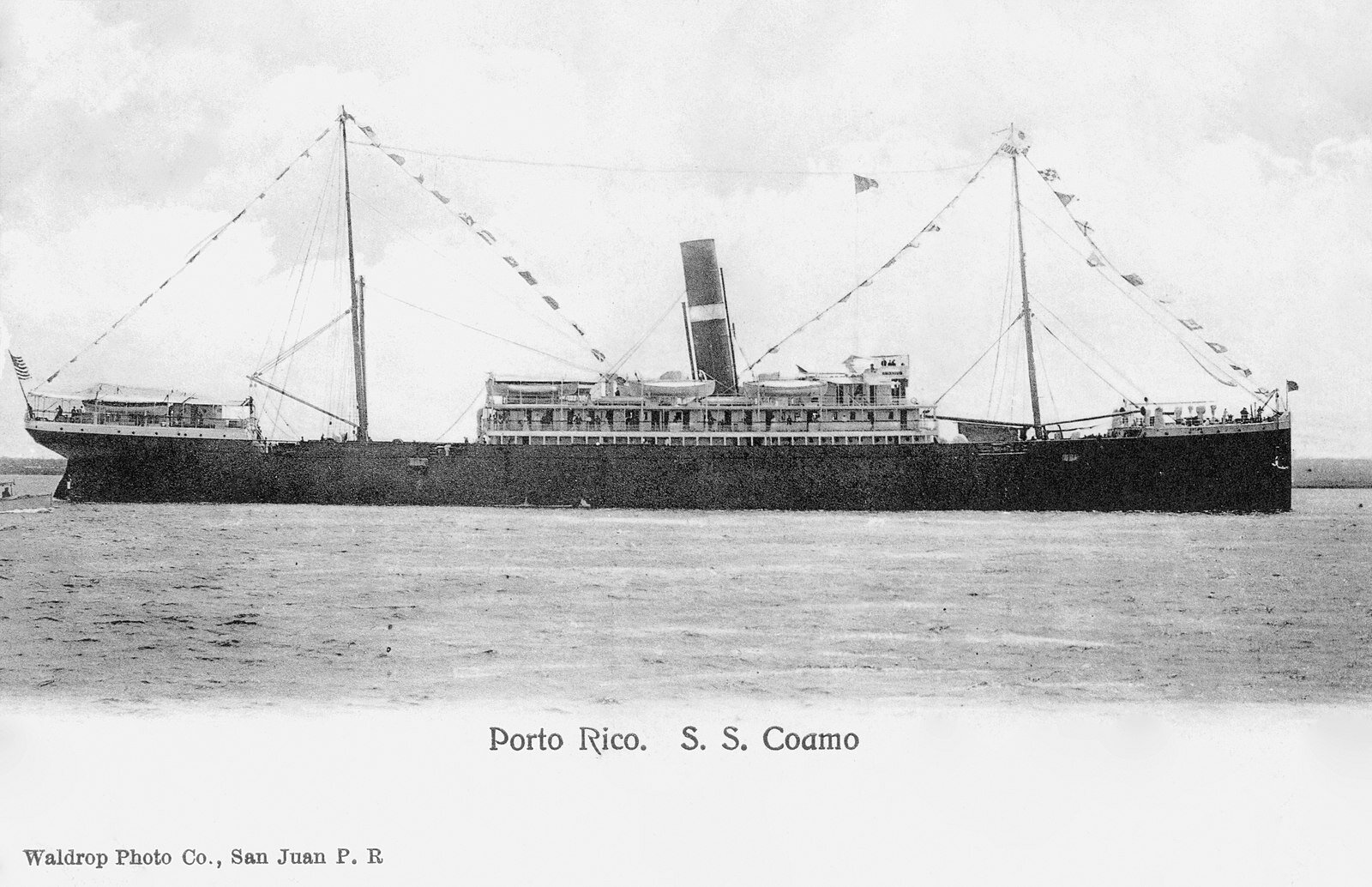

Early Puerto Rican migrants travelled by steamship and it was often a memorable experience:

When the fourth day dawned even those who had spent the whole trip cooped up in their cabins showed up on deck. We saw the lights of New York even before the morning mist rose. As the boat entered the harbor the sky was clear and clean. The excitement grew the closer we got to the docks. We recognized the Statue of Liberty in the distance. … In front of us rose the imposing sight of skyscrapers–the same skyline we had admired so often on postcards. Many of the passengers had only heard talk of New York, and stood with their mouths open, spellbound.[9]

S.S. Coamo. Postcard from the Waldrop Photographic Company. This ship was part of New York and Puerto Rico Steamship Company. Wikimedia Commons.

These trips took four to eight days and could be fun or exhausting. In an interview for the Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Flora Acosta, who migrated to New York in 1927, remembered being seasick during her entire five-day journey.[10] In contrast, Maria Fortún described her trip as an adventure, eating and dancing during her eight-day long trip.[11] Women who traveled to New York often had a traveling companion. In her interview, Carolina Velázquez recalls her seven-day long trip to New York City in 1930 to find work. Her family arranged for an older woman who lived in her hometown to accompany her. They wanted someone to keep an eye on her but the woman became so sick on the trip that she never left her cabin and Velázquez was able to explore the ship unchaperoned.[12]

For many young women, this trip was an opportunity to reunite with family and friends as well as find employment. Lillian López recalls that her sister, Luisa, was the first to travel to New York before the rest of her family slowly joined her:

The first one who came was my sister, Luisa, an invitation of dear friends who had come over here to live. So, she really came as a sort of summer vacation, liked it, and stayed. The second one who came was Elisa, and it was here where she met the gentleman who later became her husband. …She was engaged, and then, the family came for the wedding. And like that man who came to dinner, we never went back to Puerto Rico. We stayed here.[13]

Similarly, for Belpré, what started as a trip to see her sisters and attend her own sister Elisa’s wedding ended up being the beginning of a new life for her.

From Colonia to Community

New York City presented new opportunities for Puerto Rican migrants. Most Puerto Rican women who came to New York City had family or acquaintances who helped them navigate housing, jobs, and transportation. Carolina Velázquez recounts learning to clean houses from her sister who bought her along to teach her how to work and once she knew what to do, she did the job on her own.[14] Belpré's sister was instrumental in helping her start her career. Elisa Belpré Maduro recommended Pura for the job of library assistant because Maduro’s husband did not want Elisa to work outside the home. However, many Puerto Rican women “engaged in activities designed to supplement family incomes, and various home-centered economic ventures emerged in response to their economic needs.”[15] They realized they had to work, sometimes outside the home, to contribute to the household income while still taking care of their domestic responsibilities.[16] Velázquez mentions that she would give her sister part of her money to contribute to the household. As historian Virginia Sánchez Korrol demonstrates in her groundbreaking book on Puerto Ricans in New York City, From Colonia to Community, Puerto Rican women were foundational to the formation and maintenance of Puerto Rican communities in New York City.[17] Puerto Rican women were the information and support networks that facilitated the migration process. They had to learn to navigate the challenges of their new homes in an unfamiliar language. They had to figure out the school systems and hospitals, how to obtain housing and find work, and everyday household tasks like shopping.

Needlework was a home-centered economy that transferred from the island to the mainland. In “‘En la aguja y el pedal eché la hiel’: Puerto Rican Women in the Garment Industry of New York City, 1920–1980” historian Altagracia Ortiz uses oral histories to recount the experiences of Puerto Rican women working in the garment industry and living in New York City.[18] Puerto Rican female needle workers became a noticeable part of the garment workforce in the 1920s. They worked primarily from home, making very little money, supporting Sánchez Korrol’s findings that Puerto Rican women tried to take care of the home yet still found a way to make money. Like Sánchez Korrol, Ortiz found that “Puerto Rican women working in this industry during the 1920s and 1930s… dedicated themselves exclusively to home needlework despite low wages because it allowed them to supplement their husbands' incomes while they cared for their families.”[19] Through the oral histories of elderly Puerto Rican seamstresses, Ortiz learned about the issues and obstacles the pioneer Puerto Rican women encountered in the garment industry and how they went about resolving them.

“These workers developed an informal system of networking, consisting of relatives, friends, and comadres (godmothers of their children) who found them employment, guided them to distant factories, eased communication with English-speaking employers and coworkers, and cared at times for their children.”[20]

As Sánchez Korrol also mentions, these women devised an “informal informational network” to overcome these obstacles.[21]

Orgullosa de ser Boricua[22]

Both Centro: Center for Puerto Rican Studies and the Brooklyn Historical Society have oral history collections on Puerto Ricans who migrated to New York City in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the women interviewed for these projects worked in garment factories. Since sewing was a major industry in Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican women could translate their skills to the factories in New York. The garment industry was such a major employer of Puerto Rican women that Centro’s Oral History Task Force project “Puerto Ricans in New York - Voices of the Migration” was able to produce and broadcast a radio program in 1984 called “Nosotros Trabajamos en la Costura” (We Work in the Garment Industry) where Puerto Rican women discussed their experiences working in the garment industry in New York City.[23]

Women proudly described how hard their mothers worked in the garment industry while raising their families once they arrived in New York City.[24] Others recalled how their grandmothers were part of the first migration of Puerto Rican women, and how they used their sewing skills to get jobs in New York garment factories.[25] The program’s goal was to document their history for the Puerto Rican community.

As a gifted teacher, scholar, and cultural ambassador, Pura Belpré was also promoting Puerto Rican heritage and helping Puerto Rican migrants in the United States. She made sure that Puerto Ricans did not leave their history behind by retelling the stories she had heard in Puerto Rico. She promoted literacy for the bilingual and Spanish-speaking children but not at the cost of them losing their language. Like the other women who migrated during this period and shared their stories through oral narratives, she understood the importance of passing down culture and heritage; she had pride in the work that she did, pride in her language, and her community.

Pura Belpré’s experience was atypical in some ways but not in others. She travelled to the United States to visit her sister but ended up staying. She found her job through a friend and was active in the Puerto Rican community through education and literacy programs. However, her work was professional, not in the factories. She probably did not experience the same obstacles as her fellow Boricuas, including the language barriers or the housing and job searches, but her promotion of literacy and bilingualism suggests that she was aware of the obstacles faced by other Puerto Rican and Spanish-speaking migrants.

Famous Boricuas like Belpré are memorable because of the notable contributions they made to the Puerto Rican community. However, everyday Puerto Rican women also made contributions that were not as notable but still foundational in creating Puerto Rican communities. As scholars, we need to think about how we can use available sources to fill in the gaps and create a more balanced narrative of the Puerto Rican experience in New York. By seeking out and documenting diverse experiences, we can stitch together the pieces of these different women’s lives. Understanding that they came from different regions and backgrounds but were bound together as the first Boricuas in New York.

Cathy Cabrera-Figueroa is a PhD student in history at the Graduate Center, CUNY. She is also a Research Fellow at the Center for Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies. Her research focuses on Puerto Rican migration and communities, particularly the impact of the United States’ New Deal policies on the island of Puerto Rico.

[1] Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, Pioneros: Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1896-1948, Bilingual ed., Images of America (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2001), 7. I borrowed the term “pionera” in the title of this article from this book.

[2] Carmen Teresa Whalen and Víctor Vázquez-Hernández, Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives (Temple University Press, 2005), 15–16.

[3] By incentive, I mean there was not a larger interest in the Puerto Rican community until the 1960s and 1970s when Puerto Ricans became more visible in social and civil rights issues and interest in them as a community grew.

[4] Pura Belpré, The Stories I Read to the Children: The Life and Writing of Pura Belpré, the Legendary Storyteller, Children’s Author, and New York Public Librarian (New York, NY: Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 2013), 205.

[5] Virginia Sánchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948, Contributions in Ethnic Studies, No. 9 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1983). Bodegas are corner grocery stores, barberias are barber shops, and botanicas are stores that sell spiritual and religious merchandise.

[6] Lawrence Royce Chenault, The Puerto Rican Migrant in New York City, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1970), 58.

[7] “Julio Hernández-Delgado Audio Tapes, Archives of the Puerto Rican Diaspora, Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, CUNY.” Interview with Mary K. Conwell, Tape 1, Side A.

[8] Lillian López Papers, 1928-2005. Lillian López interview with Pura Belpré on February 14, 1976, Tape 1, Side A: LiLo.PBel.02.14.1976.b07.1a. Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives, Hunter College, CUNY. Web. 12 May 2019., n.d.

[9] Bernardo Vega, Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto Rican Community in New York, ed. César Andreu Iglesias (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1984), 6.

[10] Acosta, Flora, Oral history interview conducted by Jaime Barreto, November 05, 1974, Puerto Rican Oral History Project records, 1976.001.001; Brooklyn Historical Society., n.d.

[11] Fortún, Maria, Oral history interview conducted by Jaime Barreto, December 23, 1974, Puerto Rican Oral History Project records, 1976.001.021; Brooklyn Historical Society., n.d.

[12] Velázquez, Carolina, Oral history interview conducted by Mayda Cortiella, August 06, 1974, Puerto Rican Oral History Project records, 1976.001.065; Brooklyn Historical Society., n.d.

[13] Lillian López Papers, 1928-2005. Lillian López interview with Pura Belpré on February 14, 1976, Tape 1, Side A: LiLo.PBel.02.14.1976.b07.1a. Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives, Hunter College, CUNY. Web. 1 May 2019., n.d.

[14] Velázquez, Carolina, Oral history interview conducted by Mayda Cortiella, August 06, 1974, Puerto Rican Oral History Project records, 1976.001.065; Brooklyn Historical Society.

[15] Rodríguez and Sánchez Korrol, Historical Perspectives on Puerto Rican Survival in the U.S., 58.

[16] Foner, From Ellis Island to JFK, 115-118.

[17] Sánchez Korrol, 85.

[18] Altagracia Ortiz, “‘En La Aguja y El Pedal Eché La Hiel’: Puerto Rican Women in the Garment Industry of New York City, 1920–1980,” in Puerto Rican Women and Work, ed. Altagracia Ortiz, Bridges in Transnational Labor. Temple University Press, 1996, 55–81. En la aguja y el pedal eché la hiel literally means on the sewing machine needle and pedal I poured my bile, figuratively it means to work very hard

[19] Ortiz, “‘En La Aguja y El Pedal Eché La Hiel’", 56.

[20] Ortiz, “‘En La Aguja y El Pedal Eché La Hiel,’” 58

[21] Sánchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community.

[22] Proud to be Puerto Rican

[23] “Puerto Ricans in New York: Voices of the Migration” was a three-year oral history project by the Centro Oral History Task Force whose focus was to interview community leaders, garment workers and early community migrants and recover primary source materials. It resulted in several public presentations on the Puerto Rican migration experience including a radio program on women garment workers, "Nosotras Trabajamos en la Costura."

[24] CENTRO: Puerto Ricans in New York - Voices of the Migration. Nosotras Trabajamos en la Costura Radio Program (English): PRNYVM.NTELC.RadioProgram.English. Center for Puerto Rican Studies Library & Archives, Hunter College, CUNY. Web. 13 April 2019., n.d.

[25] CENTRO: Puerto Ricans in New York - Voices of the Migration. Nosotras Trabajamos en la Costura Radio Program (English): PRNYVM.NTELC.