Piecework, Peddlers, and Prostitutes: Intertwined Lives on the Lower East Side

By Deena Ecker

At the dawn of the 20th century, the stoop of 102 Allen Street, near the corner of Delancey Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side hopped with activity. Children played in front of the building, competing for space with “those women, called ‘Naphkes’”[1] who would “say to men: ‘Come up’.” Isaac Yarmus, just 12 years old, said that when he “went on the stoop the Naphkes would take my hat and throw it into the street and tell me to keep away from the stoop.” Meanwhile, the building’s housekeeper, Hester Wolf, kept careful watch and would “say to the Naphkes: ‘Go inside’. when she saw a policeman or detective coming along the street.”[2]

This image, from 1901, is a few blocks east of 102 Allen Street. "Manhattan: Willett Street - Delancey Street," New York Public Library.

Once inside, the first stop a man would make if he were looking for a night of drinking, gambling, and sex, would be to the Wolfs’ apartment where Hester’s husband, Henry, held court. This apartment was also where tenants in the building went to sign rental agreements and pay their rent every month. This administrative chore occurred in the same location as the illicit business of cards, booze, and prostitution.[3] Like many buildings in the neighborhood, at 102 Allen Street, people who did not participate in the illicit economy and culture of prostitution lived side by side with those who did. Often the worlds are seen as separate: “honest citizens” and prostitutes. But nothing is that clear-cut.

In 1901 the Committee of Fifteen formed in New York City to tackle the perceived problem of prostitution in the city.[4] These men, mostly wealthy businessmen and academics, hired about 20 working-class men to pose as customers, investigate the tenements, brothels, and saloons, and report back on their experiences.[5] While the perspectives of the Committee and other similar reformers have been previously studied, the perceptions of those who lived with prostitution as part of their daily lives have not been thoroughly explored. This includes the investigators hired by the Committee, community members who lived among prostitutes (in their buildings and in their neighborhoods), and the people under investigation — the pimps, madams, and prostitutes. By looking at 102 Allen Street, which was the most actively investigated brothel, in both the neighborhood specifically and the city as a whole, we can see the complexity of different perspectives and experiences surrounding prostitution.

These perceptions varied based on a person’s gender and class, whether they participated in the illicit industry, either as a consumer or a provider, and how they benefited financially from prostitution, or the investigation. By looking beyond the reformers on the Committee of Fifteen and focusing on the people who lived in the neighborhood — the prostitutes, pimps, and madams, their neighbors, and at the men who directly investigated them — we gain a better and more inclusive understanding of life on the Lower East Side at the turn of the 20th century.

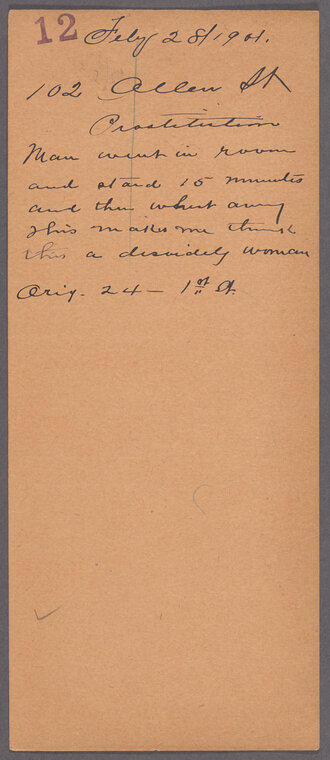

Jacob Kreiswirth’s investigations notes which show his dual identity as a neighbor and investigator. Committee of Fifteen records, New York Public Libary.

It is not usually clear where the Committee found the men they hired to carry out the investigation, but at least two of their most prolific investigators started filing reports while they resided at 102 Allen Street. For Jacob Kreiswirth and Max Moskowitz, their careers with the Committee began because they lived on the site at this actively investigated brothel.[6] In the depositions they gave for this address, they listed their occupations as peddler and salesman, respectively. In all later affidavits they list their occupation as investigator, indicating that they were not employed by the Committee until after the investigation at 102 Allen Street concluded in April of 1901.[7] While the investigation at 102 Allen Street also employed the usual undercover visits by other Committee investigators, it was greatly aided by these two men acting as inside sources.

The Committee of Fifteen investigators who were most active in the Lower East Side either lived in the neighborhood or shared the ethnic and class make-up of those who did. Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrant communities populated these buildings so sending investigators who blended in provided the Committee with more useful information. The people under investigation spoke more freely with investigators than they would have with men who seemed out of place. For example, Hester Wolf shared her concerns about the investigation with both Kreiswirth and other investigators who visited the address undercover. Because they fit in demographically with the other residents of the building, they could make connections and build relationships that provided a trove of evidence for the Committee, which they would not have been able to amass without these investigators.[8]

From the first report that Moskowitz filed with the Committee, we see he opposed the prostitution in the building but for more personal and quotidian reasons than the Committee. On the first night in his new home he and his family “were kept awake until 3 o’clock in the morning… thro[ugh] the continuous comings and going of men into the premises… and loud talking.”[9] Moskowitz’s objection was the disruption to his sleep. Most of his complaints have to do with loud noises including shouting and fighting, and the effects that had on his wife and baby. As reported in a deposition, “the peace and comfort of himself and family were continually disturbed.”[10] Oftentimes, Moskowitz reported, men would knock on the doors of apartments where no prostitutes lived because a prostitute had occupied that apartment in the past.

Moskowitz had several conversations with another tenant, Jennie Hoffman, about how she managed to live in a building with prostitutes. On one occasion “she said to me there are three rooms on the top floor which would be all right for me and my wife, as we could not see what was going on on this floor.”[11] Hoffman saw that the Moskowitzes were disturbed by the prostitution and offered a practical solution to the problem. While the Committee’s published works indicate their moral objection to prostitution, the reports do not reveal the moral viewpoints held by Hoffman or the other people who lived in the neighborhood. What they do reveal is that these people devised their own strategies to coexist with prostitutes, including keeping it out of sight of themselves and their families when necessary.

Jennie Hoffman was a savvy woman who paid attention to how the landlord and the housekeeper ran the business of the building. When the landlord threatened to evict her if she did not pay her rent, she replied, “‘I will not move’. There is a woman on the third floor who pays you $20 rent; why don’t you bother her.[’]”[12] The woman Hoffman referred to, Mary Benjamin, acted as the madam of the building, as well as being a prostitute herself. (Other tenants reported paying $8, $8.50, and $10 a month.[13]) Hoffman successfully leveraged her knowledge of prostitution in the building against the landlord’s fear of being reported to the police (or the Committee). After this, he no longer bothered Hoffman and she paid her rent when it was convenient for her.

While Hoffman did not engage in prostitution herself, she profited from living among prostitutes in multiple ways. First, she did domestic labor for the prostitutes in the building. She told Moskowitz that the prostitutes hired her to wash and sew their clothing, “which enables me to live.”[14] She also saw ways to benefit financially from the Committee of Fifteen investigation. She testified for the Committee but not without financial incentive. Kreiswirth reported, “Mrs. Hoffman is a very important wittness [sic] she said if the Committee of 15. [sic] will pay her for the trouble she is willing to testify and say every thing [sic] she knows about 102 Allen St.”[15] Hoffman saw and understood what happened in the building, and in a small way, profited off of it by providing domestic services to the prostitutes. Her willingness to testify was more about money — she required payment — than it was about a desire to “clean up” the building.

With Mrs. Hoffman we also get a woman’s perspective which is missing from investigator’s reports. She displays an awareness of how these women went about their business but nothing about her testimony or the investigator’s reports of their conversations with her indicate a moral condemnation. This was simply a reality of her life. Her comment to Moskowitz that if he moved to the top floor he would not be bothered by living among prostitutes indicates her own coping mechanism of living among prostitutes. Like the investigators, who profited from the Committee while engaging in the activities the Committee sought to eliminate, Hoffman saw the opportunities around her to earn a profit and took advantage. As a working-class woman, living on the Lower East Side, she had more in common with the prostitutes than the investigators or the other male tenants. This gendered difference in perception is visible even within her own marriage.

Hoffman’s husband, apparently unaware that Kreiswirth worked for the committee, warned Kreiswirth’s wife to, “‘tell your husband that he shall keep away from this d---- whores; he shall not do any business with them.” Mr. Hoffman’s attitude toward the prostitutes is far more condemning than that of his wife. It is unclear whether or not Mr. Hoffman knew his wife benefitted financially from the prostitutes. If he did know, his behavior indicates that he did not approve. If he did not know of his wife’s labor, it tells us that she kept it secret either to protect herself from the kind of verbal abuse that her husband displayed here, or to hide her earnings from him entirely. Even within this one household we can see variation that can be explained as a different perception based on gender. Mr. Hoffman went on to warn Mrs. Kreiswirth, “tell your husband… he shall not ask my wife any questions because she would not tell him anything.” This indicates a husband’s protective (or possessive and controlling) instinct.[16]

Moving from the Hoffmans and the investigators who lived at 102 Allen Street, to the prostitutes, we need to remember that they existed in the same space. The lives of prostitutes were highly visible to their neighbors. The Wolfs’ apartment was the hub of illicit activity in the building. Several women, some of whom the Wolfs called their daughters to investigators and customers, were there to serve drinks and sell sex. While Nellie and Rosy are listed on the census as Wolfs, the investigators had reason to believe that they were not actually the couple’s biological daughters.[17] Moskowitz reported, “The housekeeper’s family seems to be increasing with daughters… the daughters go as no respectable woman would go around the house.” Often the fact that these women were not actually kin is voiced by the investigators as a suspicion with no evidence, but on this occasion, Moskowitz reported “What surprises me a great deal, the father and mother are Americans and speak English fluently. The daughters speak with a foreign accent.”[18] Claiming familial relationships might be seen as a strategy to feign respectability or it could have been a sly, humorous euphemism, as the actual business taking place in the apartment appears to have been an open secret. Whether or not they were actually a family is less important than the fact that they replicated the familial structure of the other working-class people in the neighborhood. They lived and worked together in ways that indicated that they were not so different from their neighbors.

Like other working-class people of the time, prostitutes consumed popular entertainment. On one March evening, two prostitutes lay down in the open-plan bedroom in the Wolfs’ apartment. They said they had been out at a ball until 8 AM the previous night and were too tired to do anything other than lay on the bed. This ball, which was sponsored by the building owner, Martin Engel, was an exciting affair, complete with a brawl. For Engel to both own the building and to sponsor this kind of entertainment speaks to the interconnectedness of prostitution, amusements, and violence.[19]

A calling card for Nellie. Committee of Fifteen records, New York Public Library

Entertainment could also be seen as a problematic distraction for prostitutes who took their work more seriously than their amusement. Mary Benjig aka Mrs. Benjamin aka Mary Kauminer sometimes acted as a madam in the building, managing the other full-time prostitutes on the premises, including the Wolfs’ supposed daughter, Nellie. Benjig complained to Jennie Hoffman “that Nellie Wolf was not much good for business because she went out to the theatres too much and she [Benjig] had to send customers away.”[20] Benjig obviously took the business part of her profession more seriously than Nellie, who preferred to spend her time enjoying the latest entertainments. Consumer culture is another location where the experiences of prostitutes were not so different from the experiences of working-class women of this time.[21]

In 1901, the Lower East Side was a nexus of activity, where people from numerous different walks of life interacted. Factory workers and peddlers lived side by side with prostitutes and pimps. These people navigated their lives and their interactions with one another in ways that reveal a variety of perceptions about vice, morality, and the necessity of earning a living. When the Committee of Fifteen enlisted locally-based investigators to report on prostitution, they inserted yet another set of perceptions and motivations into an already complex local economy. Their role as paid investigators and their connections to the Committee influenced their perceptions about prostitution. However, those perceptions more closely aligned with others who resided in the neighborhood based on the shared daily experience of living amidst a culture of sex work.

In looking at prostitution on the Lower East Side at the turn of the 20th century, we often separate the lived experience of people who did not participate in this illicit economy from the realities of prostitutes, pimps, and madams. But it is critical to remember that these groups lived side by side. Even when women did not engage in prostitution themselves, they could financially benefit from the institution through their domestic labor. Complaints about noise from men coming and going into the apartment across the hall all night are very different from the moral objection that the Committee of Fifteen had to prostitution, even if they resulted in the same punitive action. As the microcosm of 102 Allen Street demonstrates, for working-class people on the Lower East Side, prostitution was a fact of life to be navigated, whether by ignoring it, opposing it, engaging in it, or benefitting from it.

Deena Ecker is a PhD student in History at the Graduate Center, CUNY and the managing editor of Gotham. Her work deals with prostitutes and prostitution in New York City in the early 20th century.

[1] Naphke is the Yiddish word for prostitute.

[2] Committee of Fifteen records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library (hereafter CO15) Box 8 Folders 10-16, 102 Allen St., Yarmus affidavits, 3/15/01. I accessed the CO15 records both in the library and online. Not everything from the collection is digitized but what is digitized can be accessed at http://archives.nypl.org/mss/608#detailed.

[3] Ibid.

[4] The original goals of the Committee of Fifteen also included investigating gambling in New York City, but most of the investigations focused on prostitution.

[5] CO15 Box 3 Folder 1.

[6] A man by the name of Henry Hoffman also lived in the building. There was a Henry Hoffman employed as an investigator by the Committee but the ages and addresses of the two men do not match. Additionally, while Moskowitz and Kreiswirth submitted several reports to the Committee for this address, Hoffman does not. Hoffman did give a deposition regarding 102 Allen St. This is one of several depositions given by the residents of the building, including his wife.

[7] CO15, Box 8 Folders 10-16.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line], (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004), Manhattan, Enumeration District 180. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7602/images/4114591_00850?ssrc=&backlabel=Return&pId=19150940 (accessed 8/15/20)

[18] CO15, Box 8 Folders 10-16.

[19] CO15, Box 8 Folders 10-16. Brothers Martin and Max Engel are both stated to be the owners of 102 Allen St. at different points in the records. While the evidence supports Max being the real owner, in this incident, Martin is stated as the owner.

[20] Ibid.

[21] For more on working-class women and consumer culture, see Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.