NYC's Lost Neighborhood Courthouses

By Robert Pigott

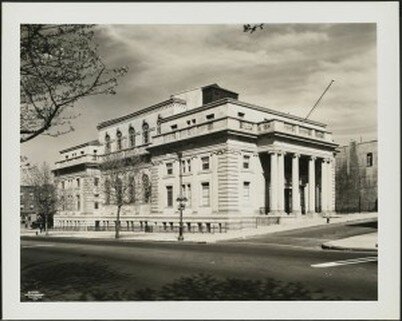

The former Sunset Park Courthouse (Courtesy of The Museum of The City of New York)

When most New Yorkers think of courthouses, they visualize Foley Square in lower Manhattan or perhaps Court Street in Brooklyn. But there was a time when the City’s courthouses were not so centralized. If you travel to Brooklyn’s Sunset Park neighborhood and walk along 42nd Street towards the East River, when you get to Fourth Avenue, you will come upon a truly majestic building. An apparently recent sign out front says “Community Board 7.” But engraved in stone over the entrances on opposite sides of the building are the words “MAGISTRATES COURT” and “MUNICIPAL COURT.” This building unlocks the story of New York City’s lost neighborhood courthouses.

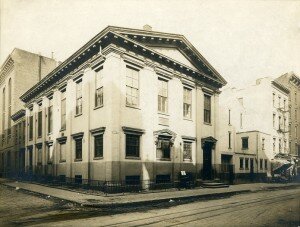

Jefferson Market Courthouse (Reprinted from New York Then and Now by Edward B. Wilson, courtesy of Dover Publications)

Until a 1962 amendment of the New York State Constitution, there were Magistrates’ Courts handling minor criminal matters and Municipal Courts for small civil cases. By 1962, these courts had been abolished, and the City’s courthouses were largely centralized in each Borough. But from the late 19th century through the early 1960s, you could find courthouses in every corner of New York City. Some were very modest structures that you would not expect to have been preserved. Others were very grand structures that either have been put to new uses or are sadly lying fallow.

Two of the oldest and grandest neighborhood courthouses are still standing: the former Jefferson Market Courthouse and the Harlem Courthouse.

Built between 1874 and 1877 as the Third Judicial District Courthouse, the Jefferson Market Courthouse, located on Sixth Avenue between Greenwich Avenue and West 10th Street, remains a Greenwich Village landmark, albeit serving a very different function. Designed in the American High Victorian Gothic style by the firm Vaux & Withers, it was built to house the Police Court and the District Court. In 1906, Henry Thaw was indicted in this courthouse for the murder of architect Stanford White, whom Thaw suspected of dallying with his wife, the former actress Evelyn Nesbit. Reflecting its judicial function, the building’s sculptural detail includes the trial scene from The Merchant of Venice. The Sixth Avenue El rumbled past the courthouse from 1878 to 1939. By 1958, the building had not been used as a courthouse for over 10 years, and the City was planning to sell the entire block to private developers. Before the enactment of New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Law, a grassroots preservation group succeeded in eliciting the support of then Mayor Robert Wagner, who prevailed on the New York Public Library to acquire the building for a branch library, which it remains to this day.

Harlem Courthouse (Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives)

In the late 19th century when the Harlem Courthouse was built, Harlem was still virtually a suburb, not yet linked to midtown and lower Manhattan by subway. Although the City has since grown up around it, this 1893 Romanesque Revival structure retains the air of a village courthouse. Located on East 121st Street, the courthouse once faced Sylvan Court, a block-long street that is now essentially a parking lot. The original judicial functions of the building—a Police Court and District Court—ended in 1962. But, as we shall see, its judicial career was not over.

Not all neighborhood courthouses were as stately as the Jefferson Market or Harlem Courthouses. For example, in the 1930s, the Fifth District Municipal Court was located in rooms above a movie theater on Broadway and 96th Street, and the public entered the courthouse through the theater lobby. With the gentrification of the Upper West Side, the movie theater that housed the courtrooms, the Riverside Theater, and the adjacent Riviera Theater were torn down in 1976, to make room for The Columbia apartment building.

Essex Market Courthouse (Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

The most exotic legal proceedings may have taken place in the long-demolished Essex Market Courthouse, which stood on Essex Street between Broome and Grand Streets from 1856 to the early 1920s. During that time, those Lower East Side pushcart operators unfortunate enough to be brought before a Magistrate for peddling without a license were likely to find themselves in the Essex Market Courthouse. Though they made their livelihood hondling, the pushcart operators, because of language barriers, often retained one of the many colorful members of the Essex Market Bar Association to negotiate their fines down to $1.00 or less. Thus, members of Essex Market Bar Association, such as its dean, “Rosey the Lawyer” (né Hyman Rosenschein), needed to be equally proficient in both Yiddish and English. President James Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, in a prior legal career, had practiced there. The Essex Market Court House was razed in the late 1920s to make way for Seward Park High School.

Coney Island Magistrates’ Court (Courtesy of The Brooklyn Historical Society)

One of the most colorful neighborhood courthouses, the Coney Island Magistrates’ Court, formerly on West 8th Street, was depicted in a 1951 article in Collier’s magazine (one of the many popular national magazines in the pre-television era):

The court is hidden away on a dingy side street and is virtually unknown to the fun seekers who throng to Surf Avenue, the Island’s ancient main stem, a few hundred feet away. Yet to a handful of cognoscenti who have discovered its charm, it rates as a Coney Island attraction on a par with Steeplechase Park …. Coney Island Court is one flight up in a faded tan brick-and-sandstone building which has come to be known as the Little Brown Jug at Coney Island. Downstairs in the 60-year old edifice is the 60th Precinct Police Station.

The article goes on to describe the minor miscreants coming before Magistrate Charles E. Ramsgate, ranging from bootleg knish peddlers to a man arrested for changing into his bathing suit while wearing his wife’s dress for cover. The Coney Island Magistrates’ Court was shut down in 1958, and the building that housed this courthouse/police station was torn down, replaced in 1971 with a police station–only building.

Williamsburg Magistrates’ Court (LaGuardia and Wagner Archives | NYC Municipal Photograph)

Two former neighborhood courthouses crossed the Church-State divide, travelling in opposite directions. The first, going from the secular to the spiritual side, is still standing on the Williamsburg Bridge Plaza at 117-185 South 5th Street. Its original function was short-lived. It was built in 1906 by the Williamsburg Trust Company, one of many banks that failed after the Panic of 1907. From the 1920s to 1958, it was the Williamsburg Magistrates’ Court. Now, several crosses adorn the building, as it is home to the Holy Trinity Church of Ukrainian Autocephalic Orthodox Church in Exile. Celebrated New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell (1908-1996) was taken with the building. In his unpublished memoirs, he related that every so often, riding on the bus, he would see an “old building I feel drawn to—it exerts a kind of psychic pull on me.” As Mitchell’s memoirs reveal, the Williamsburg Magistrates’ Court was one such old building for him.

Brooklyn Traffic Court (Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives)

The neighborhood courthouse that underwent a reverse change, from spiritual to secular, was the Brooklyn Traffic Court, formerly located at 1005 Bedford Avenue. In 1891, Brooklyn’s oldest Jewish congregation, K. K. Beth Elohim, built an impressive Romanesque Revival temple on the corner of Bedford and Lafayette Avenues. In 1921, the congregation vacated the building when it merged with another congregation. The Brooklyn Traffic Court, which had been in cramped quarters on Clermont Avenue, snapped up the vacant building, remodeling the sanctuary as a courthouse. The Traffic Court remained there for nearly 40 years, until 1962, and the building was eventually demolished in 1969. A drab brick building housing a day care center now stands on the site.

Second Children’s Court on East 22nd Street (Courtesy of The Museum of the City of New York)

First Children’s Court on East 11th Street (Courtesy of The Museum of the City of New York)

When the first Children’s Courts were opened at the turn of the last century, they were located not near the existing courthouses in lower Manhattan but in neighborhoods farther uptown. New York City’s first Children’s Court opened in 1902 at East 11th Street and Third Avenue with much fanfare. An August 24, 1902, New York Times headline announced “New York’s New Children’s Court; First Institution of the Kind in the City to Open Next Week—A Curious Judicial Experiment—Where the Court Will Hold Its Sessions—To Save Juvenile Delinquents from Contact with Crime” and went on to describe, in somewhat more florid copy than might be found in the Times today, how this new approach would take the City’s “unfortunate or slightly sinning little ones and decide upon the best way of giving them a fresh start in life elsewhere than as part of the dregs and criminals of society in police court or police station.” A mere 11 years later, in reporting on the construction of a new Children’s Court on East 22nd Street, which was “to be the Finest in the Country,” the Times reported: “the present Children’s Court … is an old, unsanitary, dark and noisy building, with elevated trains running by every minute, making it impossible for one to be heard without shouting.”

The Children’s Court’s new home, built in 1912, was the first of two courthouses to be located on East 22nd Street between Lexington Avenue and Park Avenue South, a quiet residential block near Gramercy Park. The second “Gramercy Park courthouse” was built in 1940 adjacent to the Children’s Court to house the Domestic Relations Court. (The Domestic Relations Court had been created in 1932 to assume the jurisdiction of the Children’s Court and the Family Court—not to be confused with the Family Court of broader jurisdiction created in 1962.) The adjacent courthouses would retain their judicial function until 1975, when they relocated to the new Family Court courthouse on Lafayette Street. In 1981, both courthouses were incorporated into the Baruch College campus, the main building of which is around the corner on 23rd Street and Lexington Avenue.

The West Side Court (Courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives)

There has been a slight resurgence in neighborhood courthouses in recent years. This phenomenon began in a former courthouse at 314 West 54th Street. Built in 1904 as the 11th District Court and 7th District Magistrate’s Court, it was known at various times as the West Side Court and the Night Court. Through the early 1940s, it was a beehive of activity, serving the population of the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. As described in a 1930 New York Times article, “[t]o it come all the common woes of the common people, a constant stream of human trouble. . . . The West Side Court boasts a proportion of confidence men, fur-clad women whose escorts somehow cannot keep out of fights, sleek youths with occupations as uncertain as their places of residence.”

The Magistrates’ Court and the Municipal Court moved out of the building in, respectively, 1942 and 1960. The former courthouse then served as a YMCA until the mid-1970s, its principal courtroom on the second floor transformed into a basketball court. In 1976, the old Westside Court became the home of the American Theater for Actors, a nonprofit theater company that maintains three small theaters in the building to this day.

The West Side Court’s return as a neighborhood court occurred in 1993, when the newly-created Midtown Community Court was opened there to handle misdemeanor cases emanating from the Times Square area, such as illegal vending, prostitution, shoplifting and low-level drug possession. The theater company and the courthouse coexist apparently happily, occupying different floors of the building.

Other members of the new generation of neighborhood courthouses include the Harlem Courthouse, reactivated in 2002 under the more user-friendly name “Harlem Community Justice Center,” and the Community Justice Center, opened in 1999 on Visitation Place in Red Hook, Brooklyn. But it is unlikely that the era when neighborhood courthouses dotted the City’s streetscape will ever return.

Robert Pigott is the general counsel of a nonprofit organization and a former Section Chief and Bureau Chief of the New York Attorney General’s Charities Bureau. This article is based on his recent book New York’s Legal Landmarks.