Marriage, Failure, and Exile: H.P. Lovecraft in New York

By David J. Goodwin

Horror writer H.P. Lovecraft is identified with his native city of Providence, Rhode Island and greater New England. That region — its geography, architecture, history, and lore — stood as the primary connective tissue of many of his best conceived and most popular stories, such as “The Dunwich Horror,” “The Colour Out of Space,” and “The Whisperer in Darkness.”[1] Lovecraft once declared, “Few persons have ever been as closely knit to New England’s rock-ribbed hills as I.”[2] He spent all of his adult life living and writing in a single Providence neighborhood with one notable exception — his two years in New York City between 1924 and 1926.

Lovecraft’s New York period merits study for several reasons. He belonged to a creative circle and enjoyed the constant exchange of ideas and camaraderie generated in such a community. He lived independently from his Providence family and its cloying attention. His private and published writings reveal how New York and, in general, the urban landscape informed him. However, Lovecraft held ugly views on race and immigrants, and his residing in a cosmopolitan, diverse metropolis did little to temper these beliefs. As his personal fortunes declined in New York, xenophobic and racist language and references seeped into his letters and fiction.

Providing his friends and family with little explanation, Lovecraft unexpectedly left Providence for New York on Sunday, March 2, 1924. While frantically rushing to his train to Grand Central Station, he even lost a typed manuscript that he had just finished ghostwriting for the magician, performer, and Manhattan resident Harry Houdini.[3] On the following day, Lovecraft exchanged wedding vows with a literary acquaintance and fashion industry professional Sonia H. Greene at St. Paul’s Chapel in lower Manhattan.[4] This relationship continues to intrigue scholars and readers. Lovecraft held strong and vocal nativist and anti-Semitic beliefs. The fear of “the other” is embedded in much of his work. Greene was a Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant with an unsettled citizenship status. These facts make his choice of a partner even more puzzling and underscore his own contradictory personal character.

Greene and Lovecraft first met at a writers convention in Boston in July 1921 and the pair immediately began corresponding. By April 1922, Greene convinced Lovecraft to visit New York as a guest at her apartment at 259 Parkside Avenue in Flatbush. Decades later, Greene still expressed surprise and pride at her boldness in inviting a single man of no family relation to stay at her home.[5] Lovecraft’s first impression of New York echoed that of generations of first-time visitors and transplants to Gotham. He vividly recalled his first sight of the city’s skyline from his train seat as the vehicle crossed the Harlem River:

I saw for the first times the Cyclopean outlines of

New-York. It was a mystical sight in the gold sun of late

afternoon; a dream-thing of faint grey, outlined against a

sky of faint grey smoke. City and sky were so alike that

one could hardly be sure that there was a city – that the

fancied towers and pinnacles were not the merest illusions.[6]

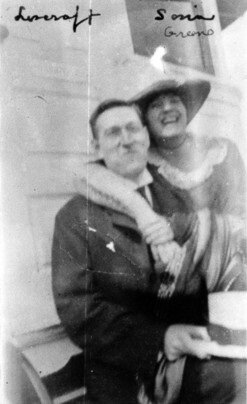

Sonia H. Greene and H.P. Lovecraft on the day of their first meeting in July 1921 in Boston. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Now, slightly less than two years later, Lovecraft found himself starting a new life in the city. As the publishing and cultural capital of the United States (and arguably the Western world) in 1924, New York was the natural destination for an aspiring writer. Greene earned a comfortable salary in her position at Ferle Heller, a high-end women’s hat and clothing shop with two Manhattan locations and several in other cities, and she was happy to subsidize her new husband’s writing career. Lovecraft had a circle of literary friends in New York and haunted bookstores and museums.[7] As an 18th-century architectural devotee, he spent many days and nights searching his recently adopted hometown for buildings and structures dating from that period or following its style. He found that Greenwich Village held a rich repository of his beloved “Georgian” age. Greene and Lovecraft enjoyed plays, movies, and restaurants. During the early days of their marriage, the future appeared bright and promising.

That quickly changed. By July 1924, Greene had left her job at Ferle Heller and opened her own millinery shop. Her business venture suffered a “disastrous collapse” by summer’s end.[8] Never having held a job in his life, Lovecraft met little success searching for work. The couple began selling household possessions to pay for daily needs. Greene suffered a physical and nervous breakdown in October 1924, recuperating for several weeks at Brooklyn Hospital (today’s Brooklyn Hospital Center) and later at a rest home in rural New Jersey. Lovecraft appeared to dedicate more time and energy to debating books with his friends and wandering all night through parts of Manhattan than attending to his own domestic affairs. On December 31, 1924, Greene left Brooklyn for a position in a Cincinnati, Ohio department store, Mabley & Carew. Lovecraft moved into a room at 169 Clinton Street in Brooklyn Heights.

Lovecraft rented a room at 169 Clinton Street in Brooklyn Heights from late December 1924 until April 1926. (Image credit: New York Public Library Digital Collections)

His relationship with New York soured throughout 1925. Echoing many New Yorkers — past, present, and certainly future — Lovecraft complained about his landlady, the heat, rodents, and his fellow tenants at Clinton Street. In May 1925, burglars robbed him of most of his clothes. Living in poverty, his diet primarily consisted of bread, cheese, and canned baked beans. He wrote little. He launched into tirades against immigrants, white ethnics, Jews, and Blacks in letters to his aunts.

Fortunately, Lovecraft’s friends ensured that his own gloom and bile did not completely consume him. George Kirk, a bookseller, lived above Lovecraft for a time at 169 Clinton Street, and the two friends would communicate with one another by banging on pipes. Another friend, poet Samuel Loveman, lived nearby at 78 Columbia Heights. The three friends and others in their social circle shared many late nights in automats and coffee shops. Lovecraft continued to hunt the metropolitan region for remnants of colonial and early American history, venturing into New Jersey, the Hudson River Valley, and Long Island.

Frank Belknap Long, H.P. Lovecraft, and James F. Morton at the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, Bronx, New York, April 1922. (Image credit: H.P. Lovecraft Photo Gallery)

Lovecraft fled Brooklyn for Providence in April 1926. Discovering that New York had provided him with the distance to appreciate fully his native region, he entered his most fertile period as a writer. Greene and Lovecraft maintained a long-distance relationship until divorce proceedings began at Greene’s insistence in January 1929.[9] He would periodically visit New York throughout the rest of his life to see friends. Until his death in 1937, he continued to view New York as a warning to his beloved Providence, as a city lost to immigrants and minorities. In an unmailed letter found on his desk after his death — possibly his last piece of writing — Lovecraft referred to New York as “the pest zone.”[10] Still, he could not completely escape nostalgia for this period in his life. Lovecraft reflected upon his two years in the city in a May 1936 letter to a New York friend, poet Rheinhart Kleiner:

Age brings reminiscences. With all the drawbacks of 169 Clinton

Street … that aera [sic] of 1925 is not without its idyllick [sic] glamour!

The long informal sessions of various rendezvous—the complete

disregard of the clock—the quaint familiar landmarks … the

spirited weekly meetings … the then burning issues with no less

burning arguments—the bookshops and the tours of exploration—

surely they glow with a golden light in the perspective of eleven

long years. That age was the last of youth for our generation—

the last years in which we could feel the curious sense of the

importance of things, and that vague, heartening spur of adventurous

expectancy, which distinguish the morning and noon from the

afternoon of life …[11]

Lovecraft’s New York interlude offers potent and fresh insights into his relationship with the early 20th-century American city. Much like Eugène Atget accomplished with his Paris photographs, Lovecraft’s New York letters allow readers to explore vicariously a vanished and, at times, even idyllic city. Lovecraft never missed an opportunity to introduce a friend to a favorite spot in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. He loved pointing out buildings of faded grandeur in Greenwich Village. Meanwhile, he voiced disgust at seeing Black residents on a Manhattan subway. He cited the “herds of evil-looking foreigners” in New York as prompting him to write “The Horror at Red Hook,” a story stewed in xenophobia and racism.[12] This chapter in Lovecraft’s biography is key to understanding him as a creative figure and as an individual. His two years in New York City showed Lovecraft to be, as one early biographer described him, “a man of outstanding virtues and egregious faults; a man both lovable and hateable.”[13]

David J. Goodwin is the Assistant Director of the Fordham University Center on Religion and Culture and a Frederick Lewis Allen Room resident at the New York Public Library. Currently, he is writing a biography of author H.P. Lovecraft and New York City.

[1] Jason C. Eckhardt, “The Cosmic Yankee,” in An Epicure in the Terrible: A Centennial Anthology of Essays in Honor of H.P. Lovecraft, ed. S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (Rutherford, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1991), 79.

[2] H.P. Lovecraft to Clark Ashton Smith, August 2, 1927, in H.P. Lovecraft, Selected Letters, vol. 2, ed. August Derleth and James Turner (Sauk City, Wisc.: Arkham House Publishers, 1968), 159.

[3] This short story was published as “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” in Weird Tales (May-June 1924), a popular pulp magazine to which Lovecraft eventually became a leading contributor. Lovecraft did not receive a writing credit for the story. Lovecraft maintained professional ties with Houdini until the magician’s unexpected death in 1926. At that time, Lovecraft and his fellow Providence writer C.M. Eddy were working with Houdini on a book-length project, The Cancer of Superstition. Jeremy Mikula, “Houdini Manuscript ‘Cancer of Superstition’ Divides Opinion Over Lovecraft, Eddy Ghostwriting,” Chicago Tribune, March 31, 2016, https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/books/ct-prj-houdini-lovecraft-manuscript-auction-20160331-story.html (accessed: April 16, 2021).

[4] Greene married Nathaniel Davis in 1936. Her last name appears as both Greene and Davis in texts. For simplicity, her surname at her time of meeting Lovecraft — Greene — will be used throughout this piece.

[5] Sonia H. Davis, The Private Life of H.P. Lovecraft (West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press, 1985), 11.

[6] H.P. Lovecraft to Maurice Moe, May 18, 1922 in H.P. Lovecraft, Letters from New York, ed. S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (San Francisco: Night Shade Book, 2005), 2.

[7] Obituary of Ferle Heller, New York Times, January 13, 1964, https://www.nytimes.com/1964/01/13/archives/ferle-heller-82-former-milliner.html (accessed: April 16, 2021).

[8] H.P. Lovecraft to Lillian Clark, August 1, 1924, in H.P. Lovecraft, Letters from New York, ed. S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (San Francisco: Night Shade Book, 2005), 54. The exact dates of these events are unknown as is the location of Greene’s hat shop. It was located in either Manhattan or Brooklyn. An early account placed the shop in Brooklyn, but this has not been verified. Additionally, it is uncertain whether Greene quit Ferle Heller, was laid off, or dismissed. S.T. Joshi, I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft, vol. 1 (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2013), 507; L. Sprague de Camp, Lovecraft: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, 1975), 198.

[9] New York State divorce laws required very specific grounds at that time. Thus, Lovecraft declared that he was abandoned by Greene in court proceedings in Rhode Island. Lovecraft never signed the final divorce degree. Thus, Greene unknowingly committed bigamy by marrying Nathaniel Davis in 1936. S.T. Joshi, I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft, vol. 2 (New York: Hippocampus Press, 2013), 726-727.

[10] H.P. Lovecraft to James F, Morton, March 1937, in Selected Letters, vol. 5, ed. August Derleth and James Turner (Sauk City, Wis.: Arkham House Publishers, 1976), 436.

[11] H.P. Lovecraft to Rheinhart Kleiner, May 29, 1936, in Selected Letters, vol. 5, ed. August Derleth and James Turner (Sauk City, Wis.: Arkham House Publishers, 1976), 262. Lovecraft often used 18th-century spelling. This authorial quirk can be seen throughout his letters and short stories.

[12] H.P. Lovecraft to Lillian Clark, July 6, 1926 in H.P. Lovecraft, Letters from New York, ed. S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (San Francisco: Night Shade Book, 2005), 146; H.P. Lovecraft to Clark Ashton Smith, October 9, 1925 in H.P. Lovecraft, Lord of a Visible World: An Autobiography in Letters, ed. S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2000), 176.

[13] L. Sprague de Camp, Lovecraft: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, 1975), 7.