Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis

Editor’s Note: Today marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment. New York was at the center of the Woman Suffrage Movement, as Lauren Santangelo’s work shows us.

By Lauren C. Santangelo

Organizers hold Wall Street, open-air meeting in 1911. Photograph from Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.

Last summer, Oxford University Press published my book, Suffrage and the City: New York Women Battle for the Ballot. The book examines how leaders in such suffrage organizations as the New York City Woman Suffrage League and the Woman Suffrage Party perceived New York City, how those perceptions changed over the course of five decades, and how they informed campaign strategies. It considers how these leaders — mainly white, middle-class women and thus a subset of a larger, more diverse movement for political equality[1] — mobilized their positions to access and lay claim to parts of the city, sometimes in ways that contested racial and class divides and sometimes in ways that buttressed them. Suffrage and the City has many examples of this — from organizers demanding the police maintain order at a Wall Street open-air meeting to them taking control of a baseball stadium during “Suffrage Day.”

Suffrage and the City demonstrated that these organizers tailored their strategies to the metropolis’s different spaces, neighborhoods, and rhythms as the years progressed, even locating many key headquarters in the retail landscape of Murray Hill (a landscape one could reasonably expect women to frequent for shopping or for work) by the 1910s. Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis, a digital humanities initiative currently under development, builds from and supplements the book.[2] It maps suffrage events from five different years onto historical atlases of New York City, allowing users to visualize and trace various organizations’ spatial tactics. Since it is based on a searchable dataset, there are myriad avenues for discovery. A user can uncover, for instance, which suffrage organizations most regularly held nighttime meetings in the Lower East Side. Or they can consider why Madison Square Garden was such a popular site for events in 1910, but not 1890. They can even compare the work organizers did in Manhattan to that in Staten Island, Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx.

Shifting from writing a text-based monograph to building this interactive, digital humanities project required re-examining archives. A team of research assistants reviewed each extant issue of The Revolution, The Woman’s Journal, and The Woman Voter from 1870, 1890, 1910, 1915 (the year of a failed state referendum), and 1917 (the year New York State amended its constitution) to identify the suffrage events mentioned therein that occurred within New York City. The numbers ranged from a low of sixteen in 1890 to a high of some 1,100 events in 1915. The team coded each one, noting its location/address, time of day, and organizer. Thus, each event was investigated and recorded in the same manner, despite varying amounts of campaign investment and media coverage, helping to bring smaller occasions to the fore and preventing well-publicized activities from eclipsing them. Meetings at an organizer’s Yorkville home carry as much analytical weight as large-scale suffrage plays in midtown theatres.

In order to discern the spatial context of these events, we then identified the sites where they took place on fire insurance maps of Manhattan. Fire insurance maps are particularly useful for learning about a block or neighborhood because they brim with rich details, denoting landmarks, subway stations, restaurants, hotels, and theaters in addition to building materials and lot dimensions.

Plate from Bromley’s Atlas of the City of New York, 1897, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

(Alt text: A rectangle showing the grid pattern of a New York neighborhood. It is mainly pink with some blue and yellow.)

Locating suffrage events on them tells us more about the individual streets and neighborhoods activists selected for meetings, receptions, and protests. We can determine what was nearby an address, understand why people might be in a given area, and identify a location’s accessibility vis-à-vis major transportation hubs. If a street meeting took place next to a subway station, for instance, we can surmise that organizers were working to make their event accessible and hoping to draw the attention of passersby. The maps, thus, help us unpack suffrage strategies at the scale of the city as well as at the neighborhood and block level. Currently, draft suffrage maps of 1870, 1890, and 1910 are complete.

The 1870, 1890, and 1910 data from Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis shows that key organizations grew more active between the 19th and 20th centuries, hosting 23 events in 1870, 16 events in 1890, and some 300 in 1910. Comparing the maps themselves provides a stark visualization of the extent of this change:

Events in New York City in 1870, 1890, and 1910

(Alt text: A table showing three different maps. The left most one is from 1870 and displays a yellow bubble with the number twenty-three in it over southern Manhattan. The 1890 map includes a yellow bubble with the number ten in it over southern Manhattan as well as a green bubble over Brooklyn with the number four in it. The map to the right is of 1910 and shows yellow and green bubbles all over Manhattan as well as in Brooklyn.)

The number of events and their geographical reach on the 1910 map overwhelm when compared to the 1870 and 1890 ones. The project also demonstrates that the places used for campaign work shifted over the course of four decades. In 1870, most events occurred in commercial spaces. In 1890, most occurred in private homes. In 1910, permanent suffrage headquarters were used most frequently, an indication that the campaign had developed a foothold in the city. And, unlike 1870 and 1890, in 1910, suffrage publications report on street meetings in Gotham — spotlighting a strategy not in use earlier in the city. In fact, suffrage open-air meetings only began in 1907, when a group of “suffragettes” (radical suffragists) spoke to a crowd in Madison Square.

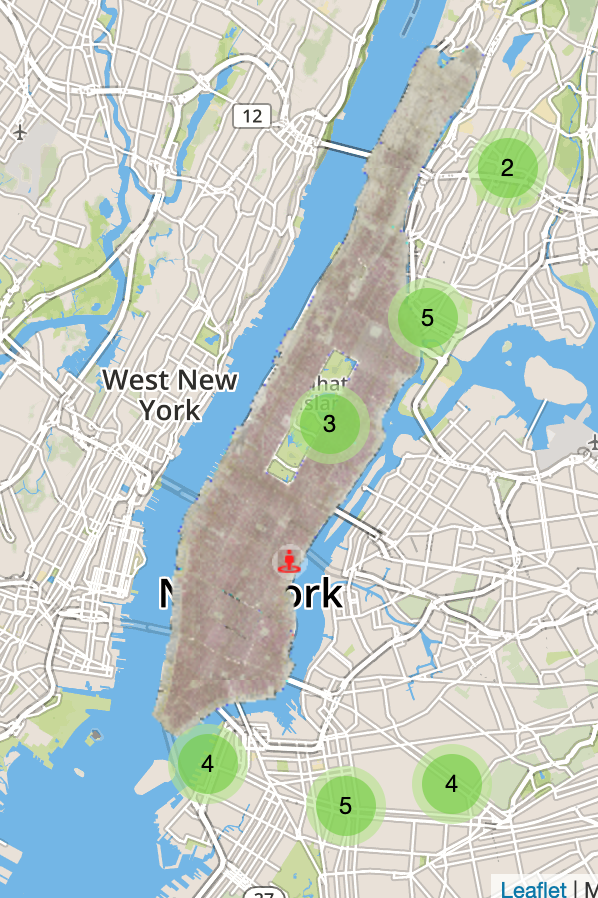

Open-air meetings in 1910

(Alt text: Rectangular map showing New York City. Three green bubbles appear over Brooklyn, with the numbers four, five, and four in them. Three green bubbles appear in Manhattan and the Bronx; the southernmost bubble has the number three in it, then five, and the northernmost shows the number two.)

Mapping these 1910 open-air meetings throws the spatiality of strategies into even sharper relief. In 1910, for instance, activists held thirty-four open-air meetings in New York City.

These were not, however, isolated to Manhattan, home of the first street meeting. More than 50 percent of the open-air meetings in 1910 took place outside of Manhattan: Brooklyn hosted 13 and the Bronx six, Manhattan claimed 15 (not all appear on the map since the publications did not provide the exact address for each meeting). Several occurred with regularity in the same place, helping to make suffrage part of a neighborhood’s regular rhythms.

Not only is space and location important; New York had a unique temporal rhythm, and a highly gendered one. Given a long history of women being suspect if alone on streets at night, Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis systematically keeps track of the time of activities.[3] According to that data, many of the 1910 open-air meetings actually happened at night (defined as later than 8PM). The maps tell us even more. One May, nighttime, open-air meeting in Harlem took place nearby several theatres, including Keith Proctors Theatre. Another nighttime meeting at Second Avenue and 86th Street happened outside apartment houses. By 1912, suffragists would hold their first Fifth Avenue torchlight parade. Reportedly twenty thousand suffragists, starting at 8PM, marched some two miles through the very heart of the city, passing iconic department stores like B. Altman’s, prestigious clubs, and numerous hotels, including the Waldorf-Astoria.[4] While the 1912 nighttime parade ran down the island’s spine, the stationary, 1910 outdoor meetings took place in more distant corners of the metropolis — ones undoubtedly central to individual neighborhoods, but not necessarily to the whole metropolis. Mapping the 1910 nighttime meetings indicates that the 1912 protest built on these earlier, more isolated actions to empower women to take up even more centrally located, outdoor space.

Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis is an extension of Suffrage and the City. But, it has a different methodological bent than the monograph. Suffrage and the City parsed and interpreted stories and events. It relied on detailed newspaper accounting, describing how crowds reacted to lectures; it took the minutes of meetings seriously, reflecting on nativist comments that stood next to demands for inclusion; and, it examined speeches, thinking about rationales and arguments. Documentation drove a significant amount of the decision-making. Featured events in The Woman Voter received detailed discussions in the book not only because we had richer information about them, but more importantly because suffragists prioritized them. It viewed decisions from leadership’s perspective and took their rhetoric seriously.

Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis shifts gears. It depends on identifying events and standardizing those events to create data points, isolating space as the key variable in the process. Meetings aimed at Italian residents of Greenwich Village, gatherings that suffrage publications barely mention, become as visible as the near-annual Fifth Avenue marches on which publications spent pages. As a result, the digital humanities project does not automatically indicate which event required the most labor and about which organizers felt most enthusiastic. Instead, it foregrounds the activity itself and strips away leaders’ rhetoric and media sensationalism about it, allowing users to hone in on the spatiality of an event — what was nearby, how accessible was it, and who was the target audience.

My hope is that Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis will ultimately empower readers of Suffrage and the City to raise new questions, thereby enriching conversations about suffrage and about New York City. Ideally, the project will also encourage users to reflect on their own orientation to research, methodology, and assumption about the archives, reminding that archives like “data are not neutral.” Choices — how records are collected, which records are preserved, and how they are approached — inform what we unearth. Suffrage and the City demonstrates that space mattered to campaign leaders; Mapping the Suffrage Metropolis curates a dataset around that finding, identifying and visualizing events in order to empower users to make their own discoveries.

Lauren C. Santangelo is a historian, teacher, and the author of Suffrage and the City: New York Women Battle for the Ballot (Oxford, 2019). They currently hold the NEH fellowship at the New-York Historical Society and in fall 2020, will return as a Lecturer in the Writing Program at Princeton University. Santangelo’s most recent research examines the experiences and resilience of young Italian-American survivors of sexual assault in the 1920s.

[1] Forthcoming scholarship by Martha Jones and Cathleen Cahill promise to center women of color’s work, reconceptualize suffrage, and tell us even more about this larger movement.

[2] Princeton University and its Center for Digital Humanities supported the project; a NEH fellowship from the New-York Historical Society provided the opportunity to continue developing it.

[3] For women in public see Jessica Ellen Sewell, Women and the Everyday City: Public Space in San Francisco, 1890-1915 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011); Mary P. Ryan, Women in Public: Between Banners and Ballots, 1825-1880 (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1990).

[4] New York Times, November 10, 1912.