Inclusive Archiving, Public Art, and Representation at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans

By Cynthia Tobar

Postcard showing view of the Hall of Fame and exterior of the colonnade, 1987. Bronx Community College Archives.

The Hall of Fame for Great Americans, created in 1900, was the first monument of its kind that sought the active involvement of Americans in nominating their favorite "Great Americans.” The Hall was conceived of by Dr. Henry Mitchell MacCracken, Chancellor of New York University (NYU), who envisioned a democratic election process for selecting these greats modeled after presidential elections. Nominations came to the election center and after a person received a certain number of votes, an NYU Senate of 100 voters made the final choice. The Senate was composed of American leaders: past American presidents, presidents of colleges, senators, and men of renown in various fields. Problems soon arose, however, when this initial process yielded 29 nominees, all male. The lack of women created a scandal and in the next election eight women were elected (currently, there are 11 women in the Hall). However, the contentious nomination of Robert E. Lee remained.

Copy of resolution from Associated Survivors of the Sixth Army Corps protesting Lee's election, November 16, 1900. Bronx Community College Archives.

Lee’s nomination and election was very much the work of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization of Southern female socialites who were the driving force behind the construction of several monuments glorifying Confederate soldiers and generals in the country. Public outcry from veteran groups such as the Associated Survivors of the Sixth Army Corps followed.

Their protest was met with bureaucratic red tape by McCracken, who claimed “During the month of October, it was entirely within the power of this Senate to reject the name of any one approved by the majority of judges, but with the expiration of that month the power of this Senate to modify the list submitted by the 100 electo[rs] expired according to the 4th rule of the deed of gift of the Hall of Fame.”

New York University Chancellor’s Office response to Associated Survivors of the Sixth Army Corps, December 13, 1900. Bronx Community College Archives.

McCracken also noted that the Senate had acquired more than the two-thirds majority needed, as well as the strong reputation of the electors. The installment of Lee’s bust in 1923 ensured that the dominant narrative behind this troubling episode of our country’s past was that in order to heal the breach between North and South, such monuments needed to be included in the Hall. The Bronx Community College Archives[1] documents the idealistic yet divisive nature of the Hall, highlighting the limits to its democratic vision when curated by a powerful and privileged elite. For those who claim that current debates surrounding the removal of such busts is an effort to rewrite history, these documents demonstrate the Hall’s own efforts to rewrite history in the 1920s by overriding public protest and enshrining the leader of a secessionist army as a “Great American.” Reflecting on the removal of the Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson busts at the Hall in 2017, there is a greater urgency for us to pause at the tensions in American life that have been left unaddressed. How can we effectively challenge the power dynamics behind these past decisions and collectively reimagine what it means to be a “Great” American? What role can civic institutions have moving forward to best support this dialogue? How can we learn from these past struggles in order to be more transparent and democratic in our approaches towards commemoration? The solution lies in creating a framework supported by inclusive archiving that actively engages with our communities so that they also can have a say in how history is told.

Maintaining archives can be a form of activism that contributes to a more dynamic view of how history is made. Librarians and archivists are in a unique position to explore the cultural and political applications of our collections, while also increasing access and supporting communities in the collective documentation of their own histories. This validates and empowers narratives from marginalized communities that have had little say in how they have been represented. Public art can also be a catalyst for this. It provides a space for discussion of politically-charged issues, using creative dialogue to address difficult issues that matter to affected community members and facilitate their path to success as informed global citizens and agents of social change. In an effort to generate new definitions of community history, creativity is essential. The Hall of Fame was created as an interactive public art monument where regular Americans could meet eye-to-eye with portrait busts of Great Americans that were created by leading American sculptors.

Part of a nationally landmarked campus in the Bronx the Hall of Fame is significant not only as the first Hall of Fame in the country, but for being the first to commemorate persons of achievement across many fields of endeavor: authors, educators, architects, inventors, military leaders, judges, theologians, philanthropists, humanitarians, scientists, statesmen, artists, musicians, actors, and explorers. Before 1900, this was an under-acknowledged area for public monuments in the United States where the dominant emphasis had been on celebrating military figures.[2]The Hall was the brainchild of its founder MacCracken, who sought to democratize the Hall by widening the scope of acclaim to include scholarly and artistic achievements as well as those of politicians and war heroes[3].

The bust of George Washington decorated with a wreath for Constitution Day, 1927. Bronx Community College Archives.

In these divisive times, the Hall of Fame continues to be the perfect setting to explore what it means of be a Great American. Recent episodes from the past few years such as the Unite the Right rally, the tragic public protest in response to the removal of the Lee statue in Charlottesville, VA, and the removal of the J. Marion Sims statue in Harlem have called into question whether such monuments in public spaces are in fact praiseworthy, and have challenged the idea of a static concept of greatness and heroism. Currently in New York City, the Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments and Markers has launched extensive public engagement initiatives to examine how art and historical commemoration is to be installed in public spaces. In the process, the City is reimagining how history is made, who gets to tell it, how it is represented publicly, and how the shared history of diverse people can best be told. It is a conversation that the Hall of Fame has much to contribute to, given its 118 years of debate, lobbying, opposition, and selection of Great Americans from across the country. As such, previous iterations of our contemporary conversation is contained in the Hall of Fame for Great Americans Collection (1894-2008) that the BCC Archives actively manages and seeks to make more broadly available. The collection consists of 110 linear feet of primary source material (i.e., documents, correspondence, artifacts and audio-visual materials) related to the selection, election, induction, commemoration and coverage of individuals elected to the Hall. A critical reframing of this history, supported by inclusive archiving and socially engaged art practices at BCC’s Archives, can positively impact how we implement more culturally responsive narratives in the historical record. This process can provide brave spaces for critical conversations that can actively interrupt silences that perpetuate racial and social injustice in our communities.

The bust of Booker T. Washington with its sculptor Richmond Barthé, 1946. Bronx Community College Archives.

At BCC’s Archives, we have embraced culturally inclusive approaches such as Community-Based Archiving, a form of archival practice that centers the stories and experiences of communities excluded and obscured in dominant narratives of the past. Practitioners of community-based archiving strive to partner with communities as they document and organize records based on four main principles[4]: 1. Reconsider the principle of provenance[5]in light of unequal power relationships; 2. Actively seek to preserve the records of overlooked communities; 3. Go beyond a purely custodial role to fill gaps in the documentary record; 4. Recognize the value of oral transmission and proactively create oral histories.

This approach acknowledges the disparities in the historical record that exclude the histories and experiences of working class communities, immigrants, communities of color, LGBTQA+, and other groups whose stories have too often been excluded from mainstream representations in American history and in traditional archival practice. We have an unprecedented need for these narratives to be widely available, to recognize the value of making space for excluded accounts of the past. In doing so, we co-create with affected communities, ensuring that there is equal representation of the needs, interests, and perspectives of all. Currently at BCC’s Archives, we are responding by revising the historical scope and content note in the Hall of Fame collection finding aid, which in archival best practices describes the overview and topics covered in a collection, in order to document how the current controversy is reshaping public perspectives.

Dr. Roscoe Brown and Bronx Community College students in front of the Hall of Fame for an appearance on the "Good Morning America" TV show, 1985. Bronx Community College Archives.

Such an approach implores those of us who work in archives to reflect on who we are doing this memory work for. This self-reflection can increase awareness and empower archivists with authentic opportunities to actively identify where underrepresented gaps exist in our collections and seek out ways where we can include documentation that allows for historical discussion from a range of viewpoints, rather than be passive absorbers of historical information. Additionally, this allows us to validate the lived experiences of individuals and groups who have been overlooked in the historical narrative by collecting their story. This type of participatory, non-static memory work engages and gives back to our communities, the ultimate users of our collections. One way we have applied this participatory community-based approach is with our oral history project “Raising Ourselves Up”: Oral Histories from First-Generation College Students at BCC, which documents the stories of first-generation college students on our campus. Oral history naturally lends itself to this work as an inclusive practice that not only documents an individual’s story, but also examines social justice themes of institutional power structures and how they perpetuate inequality among communities along race and class lines.[6]From 2016-2017, we trained these first-generation students in oral history methodology and they helped us identify and collect interviews with student narrators who provided historical and cultural insights in overcoming adversity to attain a college education. Next steps for the collection will be to use it as a starting point for public engagement around issues of equitable student access to public higher education. This was followed up in 2018 with our Getting to the Source archival internship project, run collaboratively with the History Department at BCC, which centered a structured service learning experience where History student interns attended workshops on best practices from professional archivists and historians,and engaged in historical research and archival processing of the Raising Ourselves Up collection.

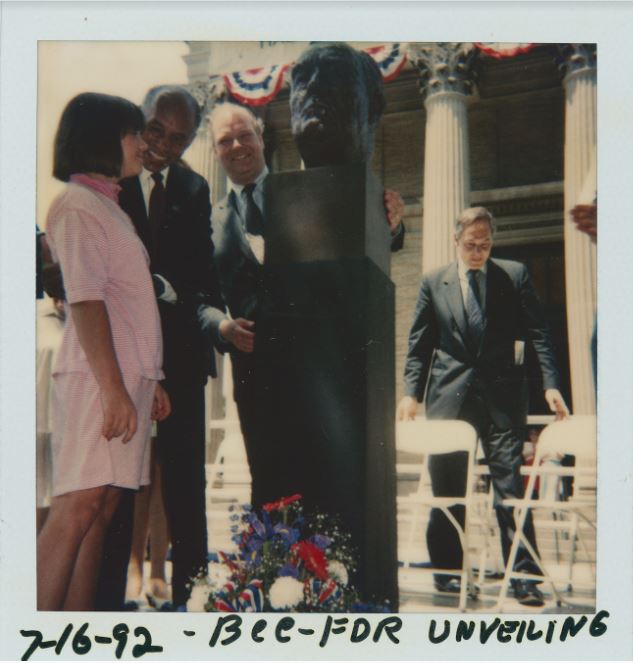

Dr. Roscoe Brown at Franklin D. Roosevelt bust unveiling, 1992. Bronx Community College Archives.

The Hall of Fame is a prime backdrop for participatory memory work. In 1973, NYU sold its University Heights Campus to the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York which bestowed the site to BCC. Yet, the Hall that we inherited commemorates largely white achievement on one of the most diverse campuses in the CUNY system serving the most marginalized students in the city. Founded in 1957, BCC’s mission has been to provide access and opportunity for academic success and social mobility to the widely diverse population of the Bronx.[7]Our students are largely low-income and are immigrants or of immigrant descent from more than 60 countries. 98% are from ethnic minorities, over one-half (55%) are first generation college-students and 53% come from households where the annual income is less than $20,000.[8]

In 2016, the BCC Archives was awarded a grant by the Diversity Projects Development Fund at CUNY to develop an online exhibit on the Hall of Fame that focused on achievement, inclusion, diversity, and power. The result was our digital exhibit, Visions of Greatness at BCC: Rethinking Racial Disparities at the Hall of Fame. Questions we examined included: How is fame and accomplishment defined and determined? What is its value to society? What is the impact of fame on those who have been recognized, and on those who have been excluded? The objective was to have this be an accessible digital tool for interaction with the monument itself, and to welcome public participation in a re-envisioned “virtual” Hall of Fame, including "greats" from the fringe, groups and individuals who have fought against the status quo. To date, the virtual Hall of Fame has collected several entries, including abolitionist Harriet Tubman, civil rights leader Cesar Chavez, and Puerto Rican actress and cultural theater icon Miriam Colon. This virtual Hall of Fame features pictures and biographies of most of the inductees, although the site will continue to evolve as pictures and information on additional inductees are submitted.

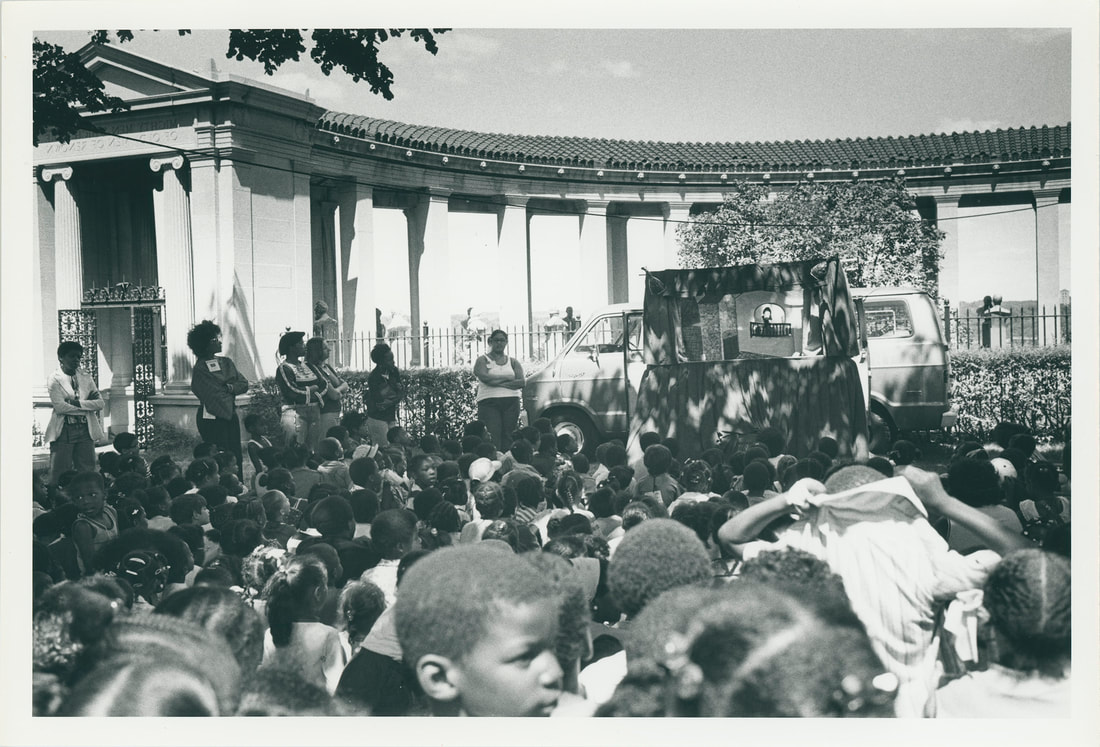

Children’s puppet show at Hall of Fame, 1977. Bronx Community College Archives.

This exhibit has served as the basis for further cultural outreach. The intent is to widen our scope from increasing access to our collections to using socially engaged art as a way to increase public interaction with the Hall. This will clear the path for us to begin re-envisioning the role that public art and monuments can play in providing a more inclusive history of the community and the country. We set out to co-create an aesthetically and politically rich community celebration alongside community stakeholders. We wanted to promote social change on interpersonal and community levels in discussions of who gets commemorated in public spaces at the Hall, and how those excluded can best advocate for their images, symbols and stories. This year-long planning process included committees made up of administrators, faculty, students, neighborhood residents, as well as local arts and culture organizations.

This spirit of inclusion has culminated in our upcoming public art event scheduled for September 21, 2019, Reclaiming the Hall: Amplifying Community Voices at the Hall of Fame. As public calls have emerged from marginalized communities seeking a more just society, we will reflect on how art and narrative continue to inform and influence culture and politics. The intention behind this event is to build the capacity of the campus, city residents and socially engaged artists to analyze, transform and become partners in the building of more democratic and equitable communities. Participating artists will explore the evolving historical context of commemoration at the Hall as well as experiment with creative interventions including photo documentation, sculpture, storytelling, and digital technologies. Drawing upon personal and collective experiences, we will explore the ways art can inform inclusion and diversity, and in turn, how social justice struggles might ground our ongoing work to increase engagement with the Hall of Fame and the Archives.

Since its creation in 2014, the Archives at BCC has been committed to listening to and supporting the work of faculty, students and public scholars who are reshaping teaching and learning about the Hall, and who are actively engaged in furthering BCC’s strategic priority of diversity and inclusion. The Hall of Fame’s history will continue to impact us as we wrestle with themes of how best to commemorate greatness, examining what was spotlighted in the past versus what we as a society value today. We are working to respond creatively to troubling histories while activating the archives to be more culturally responsive stewards of history; acknowledging that power is central to this conversation. Doing so can disrupt stagnant structures, and shift the frameworks of representation to reclaim the community’s place in memory work. This sets the stage for new interpretations of history to arise in scholarship and public art that can make a difference for future generations. This can revitalize and inform public spaces, both virtual and physical, to ensure that the rights and intentions of the community are respected, preserving their legacy for future generations while giving a voice to marginalized groups that have been left out of the historical narrative.

Cynthia Tobar is an artist, activist-scholar, archivist and oral historian who is passionate about creating interactive, participatory stories documenting social change. She is an Assistant Professor and Head of Archives at Bronx Community College, CUNY.

Notes

[1] In 1973, the Hall of Fame, along with the rest of the University Heights campus, was sold to the City University of New York (CUNY) and was designated the new home for Bronx Community College.

[2] New York University., & Morello, T. (1977). Great Americans: A guide to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.New York: New York University. P. 10.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jimerson, R. C. 2009. Archives power: memory, accountability, and social justice.Chicago: Society of American Archivists, p. 298-309.

[5] Refers to traditional archival practice where the origin or provenance of records must be assigned to a single creator rather than in the complex processes and multiple forms of creation.

[6] Janesick, V. J. (2007). Oral History as a Social Justice Project: Issues for the Qualitative Researcher. The Qualitative Report, 12(1), 111-121. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol12/iss1/8

[7] Bronx Community College. (2019) Self-Study for the Middle States Commission on Higher Education February 2019.Retrieved from: http://www.bcc.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/bcc-msche-self-study-2-7-19-1.pdf

[8] Ibid.