“I have shoes to my feet this time”: May Swenson, New York City, and the FWP

By Margaret A. Brucia

This is the second of two posts based on the early life of the New York poet May Swenson (1913-1989) and her work for the Federal Writers Project.

Drawn to New York by her exposure to Lost Generation authors and the work of Alfred Stieglitz and his circle of artists, May left the security of her loving Mormon family in Utah during the depths of the Great Depression. After struggling to hold a series of low-paying positions, withering prospects for employment threatened her continued existence in New York. By a devious route, May joined the ranks of the Federal Writers Project, plunged into New York’s cauldron of creativity, and went on to become a leader in the field of modern poetry.

S. Klein, “On the Square,” where May shopped for clothing [photograph by Berenice Abbott, 1936].

Penniless and hungry, her clothes in tatters, May Swenson was an emergency case for the Workers Alliance (WAA) in March 1938. She was fed at St. Barnabas House on Mulberry Street (“Boy, that butterless bread, gravyless potatoes, hashed turnips & salt-less meatloaf tasted swell!”)[1] and then given fifteen dollars to buy new shoes and clothing at S. Klein’s at Union Square and E 14th Street. “Jesus!” was all she could write in her diary. Like so many on welfare, even in the Great Depression, she was disgusted with herself for needing to go on relief. When a twenty-five dollar check arrived from her father, she returned it, noting, “In the letter were violets from the West slope—and honeysuckle.”

The serenity and stability of the life she had abandoned back home in Utah suffused her dreams and surfaced in poems like “Mirage.”

On the mind’s chaos a mirage

of windless valleys and of home

waits for the sleeper like a stage

to which he must nightly come

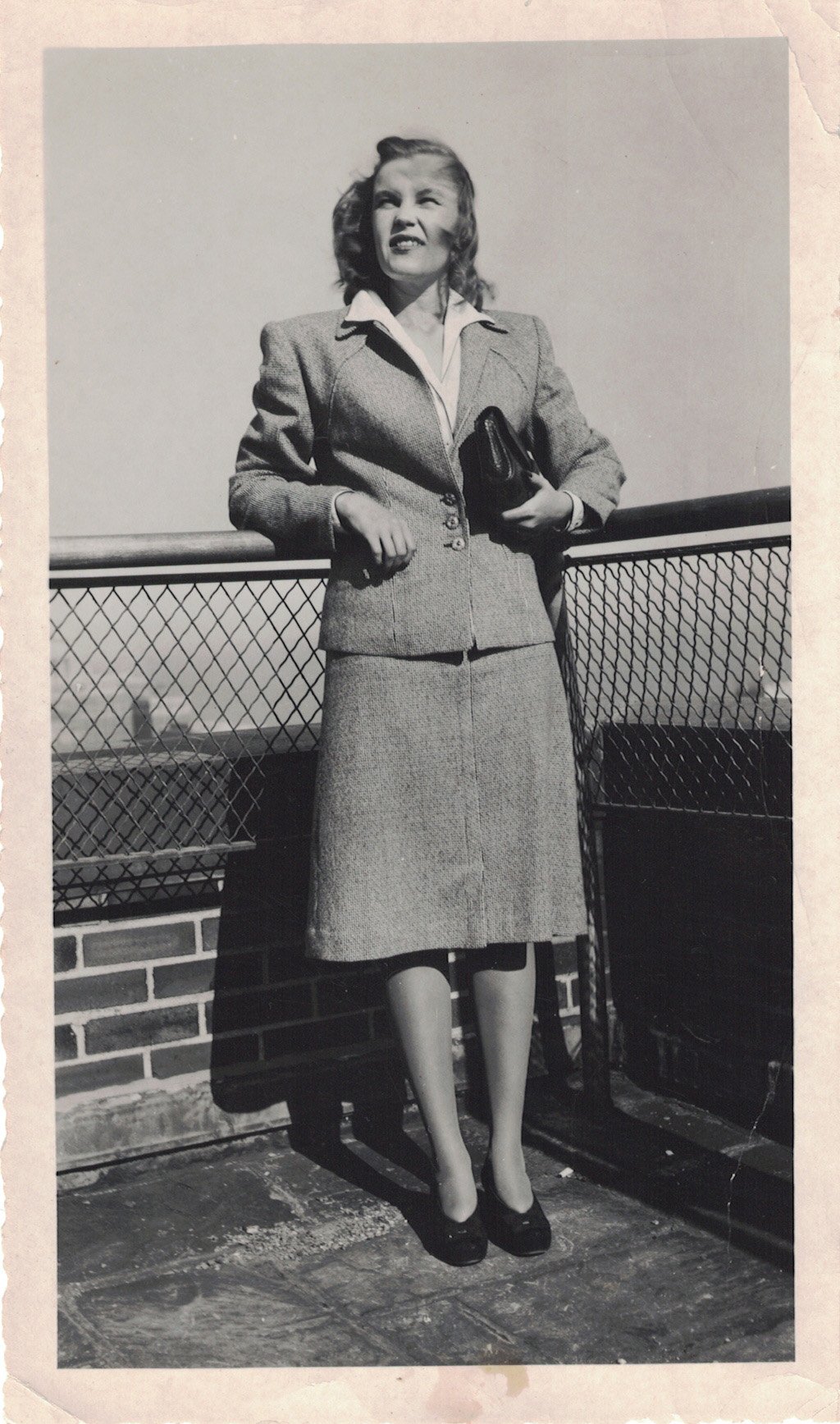

May stands proudly atop the Empire State Building, 1946 [courtesy Estate of May Swenson].

She was a New Yorker now, and resisted the nightly siren call of home. But to remain in the city she had to find work. The Federal Writers Project (FWP) was her last hope, and being on the dole was a prerequisite. Four months after her acceptance into the WAA, she was drafted as a foot-soldier in the FWP’s national army of some 6,500 writers. She was assigned to the Living Lore Unit and charged with collecting first-person narratives for an ethnological study of New York City. She traveled from the Bronx to Brooklyn interviewing anonymous New Yorkers and recording their life stories. Her “informants,” in WPA parlance, talked about their aspirations and expectations, work and leisure time, families and customs, and sometimes their homeland. May listened and took notes, deftly preserving her subjects’ style of storytelling and linguistic idiosyncrasies in her steady stream of interviews.

The unsupervised work gave her time to write poetry while still drawing an income. As the FWP historian Jerre Mangione observes, “The simple act of providing writers and would-be writers with jobs that gave them a livelihood without unduly taxing their energies turned out to be the most effective measure that could have been taken to nurture the future of American letters.”[2] The twenty-seven-member Living Lore Unit was a testament to Mangione’s assessment. Among May’s colleagues were novelist Ralph Ellison, future author of Invisible Man; musician and songwriter John Hermann; playwright and author Saul Levitt; and the leftist poet Herman Spector.[3]

One of May’s earliest informants was Anca Vrbovska, a thirty-three-year-old Czechoslovakian immigrant. Vivacious and articulate, she dazzled May with stories of the old country and her factory work in America. Charmed, May scheduled several follow-up interviews with the quick-witted woman she described as having “a mind like the Devil Himself.”

Anca Vrbrovska was a Jewish communist and published poet who had left Czechoslovakia at the age of fourteen. She was married in her early twenties, but separated from her husband a few years later. She spoke a heavily accented English, which May reproduced, revealing as much about her manner of speaking as about May’s sensitivity to the sound and nuance of language. “I was interested in noting the mixture of modern and old-world idioms informant used,” May wrote in the notes accompanying her interview.[4] She commented on Anca’s frequent use of slang, such as “Now come the real juicy part of the story.” And May also made clear the nature of Anca’s mispronunciations, recording that she said “thees” instead of “this,” “ay” instead of “a,” and had difficulty pronouncing w’s, saying, for example, “reyard” instead of “reward.”

Two months after they met, May moved into Anca’s Upper East Side apartment. The informant became her lover. The next day, May stood up her boyfriend Arnold Kates, with whom she had a date for dinner. Feeling guilty and ashamed, May sent Kates an apology note, concluding, “I want to see you. Won’t you please let me know as soon as you can—or will—grant me an evening? I await your reply.”[5] They agreed to meet in Washington Square.

He came at last out of one of those lighted streets to the dark Square. We got only part way round the fountain and I told him…. looking away, making my words as hard as I could…. After that we understood each other. It was cold and sad in the Square—a few people went by—their steps harsh upon the walk. Soon we arose and he took my cold hand, and I went. When I came home the light was warm and yellow in our house, where she sat waiting.

Anca became the love of May’s life. “We play chess and make love,” she wrote impassionedly, adding mischievously, “She is better than I at the former.” May gave Anca the nickname “Frankie,” and wrote a poem to her shortly after they met.

To F.

The el ploughs down the morning

The newsboys stand in wait

Sunlight lashes the cobbles

We reach the crosstown gate

Your bus will stop at Christopher

Mine at Abingdon Square

Your hand … “Good luck” and mine … “So long”

The taxi trumpets blare

The green light turns, a whistle blows

Our steps divide the space

Between our day-long destinies

But still I see your face

Whirling through the crowded hours

Down the afternoon

Lurking in my thoughts, your smile

Pricks me like a tune

Raven Poetry Circle members with Anca Vebrovska in front row, left (in plaid dress) [collection of the New-York Historical Society, PR 108, Raven Poetry Collection].

Before the end of the year, Anca and May had abandoned the Upper East Side for an apartment at 29½ Morton Street in the West Village, familiar territory for Anca and a new world of bohemianism for May. In the Village they socialized with members of the Raven Poetry Circle, an organization Anca helped establish in 1933. The Ravens were a kaleidoscopic assortment of students, free spirits and semi-homeless local characters — all aspiring or published poets.

The Circle sponsored a poetry exhibit and sale every spring, where the Ravens and invited guests posted their work on the fence at the southeast corner of Washington Square. Newspaper and magazine reporters promoted the show, if often tongue-in-cheek. In 1937, The New Yorker featured the Ravens’ exhibit in “The Talk of the Town.”

The poets come down from their garrets along about one o’clock (at which time the Village is regarded as officially awake), pin their poems up on the wall, and then sit around on soapboxes hopefully until sundown.…

The Poetry Circle meets once a month and has between twenty and thirty members. It used to have more, but of recent years there has been a falling off, a number of the best poets having gone on WPA and two or three having drunk themselves to death.[6]

Maxwell Bodenheim, fellow member of the Raven Poetry Circle and writer for the FWP.

Two particularly noteworthy Raven affiliates and FWP writers were Maxwell Bodenheim and Joe Gould. The FWP permitted Bodenheim, already an established author, to work on his own material at home with the proviso that he report once a week to document his progress. According to Mangione, “He would arrive … in a semi-inebriated state, then, unable to summon enough will power to enter, would go to a bar across the street to continue his drinking.”[7]

Joe Gould, bespectacled, toothless, hirsute and diminutive, was an easily recognizable Village fixture whose life, he claimed, revolved around three H’s: hangovers, hunger, and homelessness.[8] FWP permitted him, too, to work on his own recognizance. Although the hypergraphic Gould never published his magnum opus (allegedly nine million words of overheard conversations), he attracted many admirers, including e. e. cummings, William Saroyan, Ezra Pound, Horace Gregory and Marianne Moore.

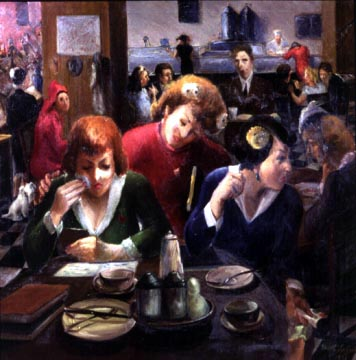

Painting of Life Cafeteria, Greenwich Village, 1936, by Vincent La Gambina [Museum of the City of New York. Gift of Vincent La Gambina, 1988. 88.10.1].

May mingled with these creative nonconformists both at work and during her free time. She and Anca attended Raven gatherings, socialized with friends, and frequented bars and inexpensive eateries. The Life Cafeteria at Sheridan Square, a gay and lesbian hangout, was a favorite. The WPA Guide to New York City described it as a bohemian establishment where “the more conventional occupy tables in one section of the room and watch the ‘show’ of the eccentrics on the other side.”[9] May and Anca, though hardly conventional, were among the watchers. May observed that “Lesbians swagger in, their arms about their girls in ruffles and giggles,” and “Les girls wear men-style coats with overlapping belts, low shoes, and short haircuts.”

Although May’s finances and love-life had stabilized, she was dissatisfied. “These days I am strangely apathetic about writing.… I think, for my part, that this is too settled an existence—I eat too well, sleep too much, and make too much money ($21.57 weekly)—it’s anathema to the imagination,” she wrote in the spring of 1939. Only a year before, poverty had been her muse when she composed poems like “Down to Earth.”

Once walking

in the city

I came

to where the

pavement broken

the earth was bare

My shoes broken

my bare feet once

felt the earth O cool

sweet

Yet during this period May submitted an impressive array of imaginative interviews. In her eleven months at the FWP, she spoke with at least a dozen people on thirty-six wide-ranging subjects. She pried information from informants about colloquial language, diary writing, dating customs, gossip and superstitions. She recorded the daily routines of factory and department store workers, loggers, radio and telegraph operators, even a tramp poet. She wrote about labor unions, gender roles in the workplace, street gangs, and life in the Navy and Coast Guard. She spoke to Hungarians, Czechoslovakians and Italians, among others, about emigration and immigration.

But May’s job with the FWP was hardly secure. Barely three months before she was hired, Congressman Martin Dies (D-TX), a vocal opponent of Roosevelt’s WPA, formed a House committee to investigate subversive activity and the spread of propaganda by fascists and communists (focusing on the latter).[10] Dies was particularly antipathetic to the Federal Theater Project and the FWP, and with his Committee to Investigate Un-American Activities (best known for its association with “McCarthyism,” ten years later), launched a series of attacks on theater people and writers. Hoping to weaken and dissolve these agencies, Dies’s committee targeted the Workers Alliance the principal relief organization for WPA employees, promoting the belief that the WAA was “a clearinghouse for Project job applications which invariably favored Communists.”[11]

May had gained admission to WAA under false pretenses. She claimed to be an orphan with no living relatives, but to give her story a modicum of credibility, claimed that she had an aunt with whom she had lost contact. “I figured that they would not bother to check up on me after I was working,” she explained later.[12] But under pressure from the Dies Committee, the WAA “made a ruling that recertification for need would be conducted every six months.” May explained the situation to her father, whom the WAA had tracked down through his sister. “I was knocked off the Writer’s Project [on] September 22, 1939 because I belonged to the Workers Alliance, a WPA union, and they cleaned out the Alliance because it contained a few Communists. They couldn’t pin the Communists down, so they burned the whole bed to get rid of the bedbugs.”

Redbaited, the FWP was gradually defunded and finally abandoned as America shifted its attention to the war in Europe in the late 1930s. In 1941, thousands of unpublished life-history interviews gathered by New York City’s Living Lore Unit fieldworkers and their colleagues across the country were hastily deposited in the Library of Congress. (Originally destined for projects left unfinished or never even begun, for the longest time they simply gathered dust. But with the digitization of the American Memories Collection by the Library of Congress in 1996, this trove of occupational, ethnographic, folkloric and linguistic first-person narratives finally became accessible. And by clicking on a link, anyone can now savor some 10,000 interviews, including May’s.[13])

Trinity Church Cemetery was the inspiration for May’s poem “Trinity Place.”

Dismissed by the FWP, May began searching for a new job in the autumn of 1939. “The weather is sharp for fall—rains all last week. But I have shoes to my feet this time—and about $50 and $20 in the bank. I’ve got to find a job.” A few months later, however, she was reinstated in the WAA and rehired by the WPA, although why and how still remains unclear. Reassigned to the US Travel Bureau Field Office in lower Manhattan, she was pleased “to get practical experience in office work.”[14] Walking home each day, she passed Trinity Church, “black with age, with the dire leaning headstones in the sparse green grass,” the subject of her December 1939 poem “Trinity Place.”

Bootblacks and tombstones

share the sun and so

do pigeons perched in Mary’s arms

in the sooty naves.

Behind the iron palings

weary grass has ceased to grow

on the muddy graves.

In dark and dreaming piety

the virgin stands at noon.

A policeman like a shepherd

parts the bleating pack of cars.

Under the worn and sacred soil

what bones are strewn?

The bootblacks kneel

on bits of chamois

by the iron bars.

***

With the pivot to World War II, however, funding of the WPA atrophied. The program was terminated in 1941. But, like so many writers, May had profited incalculably from it. She produced an enduring series of narratives for the Folklore Unit. The Travel Bureau honed her office skills and enabled her to find secretarial work throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s. And the FWP gave her the financial security to remain in New York, the city that did so much to inform her aesthetic sensibility and personal life.

Another byproduct of the experience was that the FWP enabled May to develop a facility in capturing the sound of accented English. In 1951, disinterestedly filling orders in the sales office of an industrial parts company, she typed exactly what her boss left on the Dictaphone in a flawless example of mid-century Newyorkese:

Write the Amehican Meteh Cumpny Sject O’der A 116 48 We aw in receipt uv yer replace o’der un we ah ranging to-eh ship-eh thee replace uv tree qutteh Odee qut inch wall fum ow fildelfye bwanch Pon checkin ow recurs we fine the n incowect size wus sent chu n doo t tipeegwaphica ereh n ow odeh tipin depahtment n thefoh ll b agreeable to us fo yu t return th peece sent chu in ereh by pawcel poast cullect Wed apec’ate t vehy much if yd kinely advice whetheh o nut chu t goana keep the peece oh whetheh r nut chu wunt t retain it to wus. Pargraf We gain regret tht thiserreh wus made n wait yr futhe rply Write t Wuff n Tumble Al Lectric Manufachurin Cumpny

It would not be until 1987, fifty-one years after she arrived in New York City in the depths of the Great Depression with nothing more than bald determination, that she capped her long and successful career with a MacArthur Foundation fellowship. The author of nine volumes of poetry, she died two years later at the age of seventy-six.

May Swenson needed the creative milieu of New York to attain her ambition: “You must write these poems.” The FWP gave her the means to weather the Depression and become a New Yorker.

Acknowledgements

©1943, 1950, 1956, 1991, 2013 May Swenson and Literary Estate of May Swenson. As included in Swenson: Collected Poems (Library of America, 2013. Used with permission of The Literary Estate of May Swenson. All rights reserved. Thank you to Carole Berglie and The Literary Estate of May Swenson for providing access to the Swenson materials, and to Joel Minor at the May Swenson archives at Washington University, St. Louis.

Many thanks to Peter Amram for his adroit suggestions.

Margaret A. Brucia has taught Latin in New York and Rome for many years and is a Fulbright scholar, a recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome. She is currently writing a biography of May Swenson.

[1] The Literary Estate of May Swenson. All subsequent quotations of May Swenson’s words, except where noted, are from diaries in the Literary Estate of May Swenson.

[2] Jerre Mangione, The Dream and the Deal (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996), 255.

[3] Mangione, 271-72.

[4] May Swenson, “Czechoslovakian Lore,” Folklore Project Life Histories, Library of Congress, https://memory.loc.gov/mss/wpalh2/24/2402/24020514/24020514.pdf.

[5] May Swenson, Washington University Libraries, May Swenson Collection, mss 111-01-84-3144-n.d.

[6] William Maxwell, “The Talk of the Town: Village Poets,” The New Yorker, June 5, 1937, 15.

[7] Mangione, 160.

[8] Ross Wetzsteon, Republic of Dreams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002), 422.

[9] The WPA Guide to New York City (New York: The New Press, 1992, copyright 1939), 140.

[10] For an overview of Martin Dies and his attitude toward the FWP, see Mangione, 4-5.

[11] Mangione, 293.

[12] The Literary Estate of May Swenson; this and the next two quotations are taken from a letter from May Swenson to her father, Dan Swenson, dated September 24, 1940.

[13] May’s interviews can be read online at https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/?q=May+swenson&st=gallery

[14] Literary Estate of May Swenson, letter from May Swenson to Dan Swenson, September 24, 1940.