How Do We Mourn Publicly? Memorialization and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

By Kim Dramer

John Sloan, The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, March 1911. Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the shirtwaist, a type of blouse, was the choice of fashionable New York women. Stylish women in shirtwaists embellished by intricate tucks and lace inserts cut an elegant figure on the streets of New York. But the ample cut of the shirtwaist also gave the freedom of movement required by women who toiled in the city’s sweatshops where the shirtwaists were cut, sewn and trimmed. Across lower Manhattan, garment factories sprang up in which row after row of young women sat behind sewing machines. In their pursuit of the American dream, they toiled long hours for low wages, enduring dangerous working conditions. At the turn of the 20th century, there were more than 500 blouse factories in New York City, employing upwards of 40,000 workers.[1]

On March 25, 1911, fire swept through the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Trapped by locked doors and only a single flimsy fire escape, 146 workers, mostly young Jewish and Italian immigrants, perished in the conflagration itself or jumped from windows to escape the flames and died from the fall. The Triangle Fire was the most fatal workplace tragedy in New York City history until 9/11. Today, New Yorkers walk by three small plaques marking the spot of the tragedy, many unaware of the events that unfolded at the spot more than a century ago. [2]

This article will examine three current efforts by New York women memorializing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire workers. Significantly, many of these women are the descendants of immigrants who plied the needle trades in search of the American dream. While the dreams of the young immigrant women who perished in the Triangle fire put an end to their quest, their legacy lives on in the hearts and minds of New Yorkers.

Fire in my mouth, by Julia Wolfe

They called them farbrente maydlakh, a Yiddish term meaning fiery young women. These were the union agitators, whose idealism and passion for justice organized the strikes that rocked the shirtwaist trade. The “sparkplug” of the movement was Clara Lemlich, a young Ukrainian Jewish immigrant. In 1909, Lemlich stood up in Cooper Union’s Great Hall and called for a general strike against intolerable working conditions in the garment industry. Her words were a rallying point for the Uprising of the 20,000, when thousands of garment workers took to the city’s streets.

Lemlich recalled years later: “In those days, I had fire in my mouth.” These words give the title to composer Julia Wolfe’s 2019 immersive visual and musical work, Fire in my mouth. Co-commissioned by the New York Philharmonic, the work is the centerpiece of Threads of Our City, a series exploring immigration featured in conductor Jaap van Zweden’s first season with the New York Philharmonic.[3]

Fire in my mouth is composer Julia Wolfe’s third work dedicated to labor in America. Her music is often grounded in historical and legendary narratives of American history. Her Appalachia-set Steel Hammer (2009) celebrates the life of legendary steel-driving man, John Henry. Her 2014 work, Anthracite Fields, is set in the coal mines of Wolfe’s native Pennsylvania. Fire in my mouth is set just blocks from Wolfe’s Tribeca home and the classroom where she teaches composition at New York University. Of discovering this subject for the work Wolfe said: “I thought…I need to focus on women in the workplace. And then here was this story that was just a block away.”[4]

Courtesy of nyphil.org

The work, which premiered in January 2019 to sold-out audiences at Lincoln Center’s David Geffen Hall, explores the lives of the women who perished in the Triangle fire. In Fire in my mouth, Wolfe sets the lives of the women to music in four parts that parallels their experiences: Immigration, Factory, Protest, and Fire. The 60-minute long oratorio features musicians of the New York Philharmonic joined by women’s voices from Philadelphia-based group The Crossing, and local talent from the young women of Young People’s Chorus of New York City.[5] There are 146 voices in the chorus, the same number of victims who died in the Triangle Fire on March 25, 1911.

Explains Wolfe: “Fire in my mouth tells the story of women who persevered and endured challenging conditions, women who led the fight for reform.” In each movement, the Philharmonic stage is transformed through Jeff Sugg’s lighting, video and production design, making the audience participants in the personal histories of these women. The multimedia presentation succeeds in making us confidantes, first of their dreams and hopes, then supporters of their protest against working intolerable working conditions and exhausted laborers in the Triangle sweatshop and finally, helpless witnesses to their fiery end.

New York Philharmonic, The Crossing, Young People’s Chorus of New York City perform Protest, the third movement of composer Julia Wolfe’s multimedia oratorio, Fire in my mouth in David Geffen Hall, January 2019. Photo by Chris Lee, courtesy of The New York Philharmonic.

Sopranos, Strings & Scissors

During her research, Wolfe became intimately familiar with the lives of the Triangle workers. The lyrics for Fire in my mouthcome from diaries, newspapers and archives. For the first movement, Immigration[6], she chooses the words of Triangle fire survivor Mollie Wexler:

Without passports or anything

We took a boat,

A big beautiful boat

And off we went….

To God knows what kind of future it was going to be.

Factory, the work’s second movement, recreates the noise and vibration of the factory floor. In the opening notes, strings pressed hard with a bow create a crackling sound akin the clicks of factory sewing machines stitching shirtwaists. The strings are enriched by women’s voices singing adaptations of Yiddish and Italian folk songs, representing the two groups who toiled sewing shirtwaists. The competing melodies and strings create a cacophony of human and industrial sounds-- the noise of young women toiling on the factory floor.

In Protest, the third and most dramatic movement, the audience becomes one with the striking women. As they express their hopes and struggles, the women’s choir leaves the stage to confront the audience. The girls’ choir processes down the aisles to engulf the audience in the sounds and action of their protest. They open and close heavy industrial scissors with an abrupt gesture and rasping, shearing sound. It is the sound of young lives about to be cut short.

We laid down our scissors

Shook the threads off our clothes

And calmly left the place that stood between us and starvation.

Fire is the tragic final movement that we in the audience have all waited for with dread. We know what will happen. We wait for the fiery end that will extinguish the 146 voices. The piece ends as the choir chants the names of the 146 victims in counterpoint; “The most beautiful names I’ve never heard of,” as Wolfe describes them. An honor roll of names slowly unrolls behind the stage. Name after name commands attention, insisting to be heard, honored and remembered. Through Julia Wolfe’s work, we have shared a voyage to a new life in America; shared dreams and plans with these voices. We have felt their righteous anger at long working hours with little pay and unsafe conditions. As the piece ends and the voices fade, many members of the audience were in tears. The young voices were now extinguished, but much of the talk in the audience revolved around the upcoming anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and the annual commemorations around the event each March 25th.

Chalk: Artist Ruth Sergel

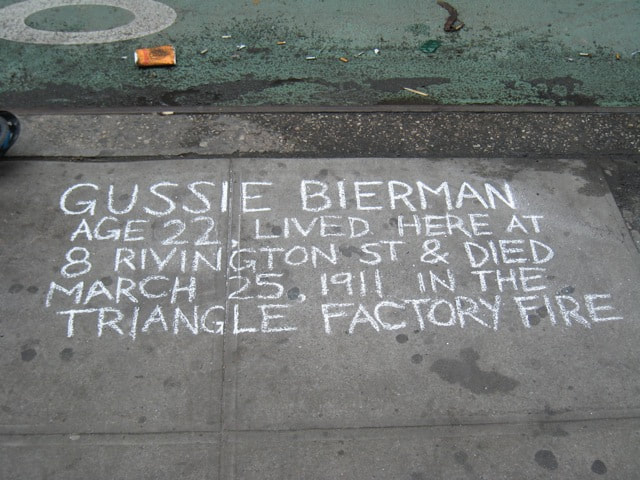

A comprehensive list of victims of the Triangle fire did not exist until 2003 when historian David von Drehle culled the names from English, Yiddish and Italian newspapers. Nearly one hundred years after the Triangle fire, von Drehle’s 2003 book, Triangle: The Fire That Changed America listed the name, age, address and cause of death of the victims.[7] As artist Ruth Sergel read the list, she realized that many of those who perished had been living in tenements just blocks from her own home.

In 2004, Sergel sent emails to thirty friends, asking them to participate in a new project to honor the victims of the Triangle fire. On March 25th, the anniversary of the Triangle fire, would they use sidewalk chalk to inscribe the name of a victim on the sidewalk in front of her home? Sergel called her project Chalk, describing it as “an annual community intervention.”[8]

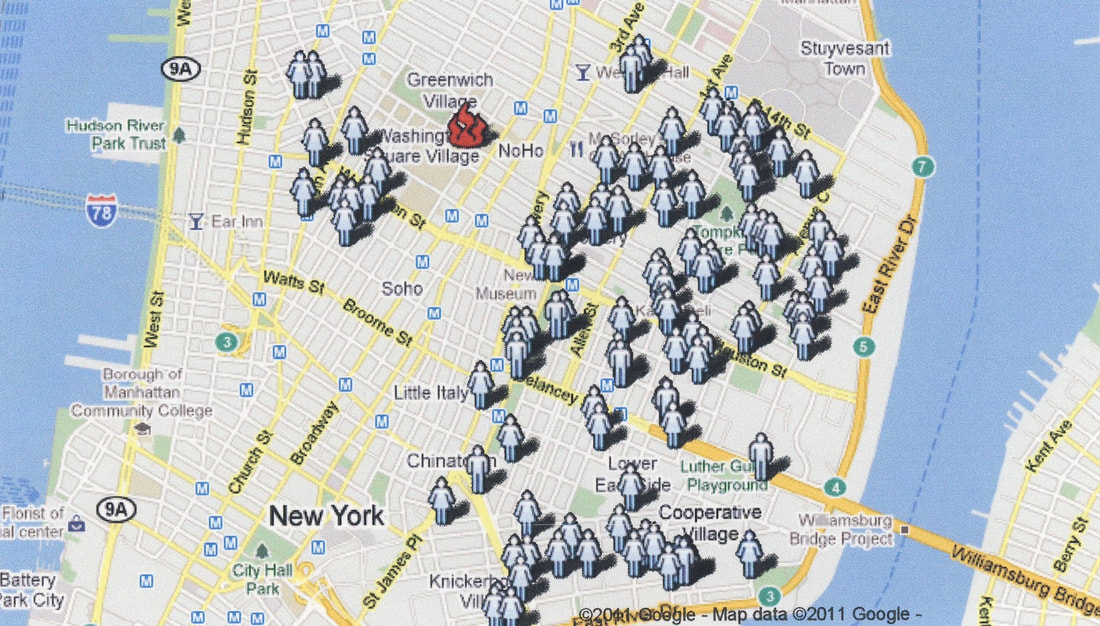

In order to make assigning names easier, Sergel transformed von Drehle’s list into a map of the city, marking each victim’s address with a small figure. On the map, lower Manhattan bristles with tiny doll-like figures, their arms stretched out stiffly.

Sergel describes those who chalk each year as “cartographers, revealing the hidden history of our city.” Each year on March 25th, as New York winter grudgingly cedes to spring’s renewal, Chalk volunteers fan out across the city. “Only by taking public action is the community that we weren’t even sure existed made visible,” explains Sergel. Each volunteer is assigned a name and address. Arriving with a printed flyer and a box of sidewalk chalk, they write the bare essentials of a life lost:

Name

Age

Address

Below each brief biography is chalked:

Died March 25, 1911

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

Says Sergel: “There are personal and unexpected ways in which storytelling and memory transform all those involved.” Kneeling on the sidewalks of the city, many who participate in Chalk develop a profound relationship with those whose names they inscribe. Their own lives become entwined with that of another, forming a bond against time and refusing to let memory die. Chalk is a mode of memorialization that emphasizes place and community stewardship. Some who chalk have begun to personalize their inscriptions, adding small pictures, flowers and additional information. Some photograph or film their participation in Chalk each year.

Through Chalk, for one day each year, until spring rain washes sidewalk chalk from the pavement, the lives of the Triangle victims become a part of our city again. The colorfully inscribed memorials are a welcome splash of color on a windy and gray March day. On the streets, shopkeepers and neighbors remember and greet those who Chalk. Often, residents offer stories of the Triangle fire they heard growing up. Passersby stop briefly to look at the inscriptions and ask questions, read the flyer or whisper a brief prayer. Others simply step over or sometimes on the inscribed pavement, New Yorkers hurrying on their way towards their own 21st century dreams.

Unlike Julia Wolfe’s composition on the Triangle fire and its victims, no ticket is required for Chalk. There is no professional orchestra under the baton of a conductor, no organized chorus singing set lyrics. Chalk was born when one New York woman contacted her friends; and they, in turn, passed along the message to others in the city. It is a memorial that plays out on the sidewalks once leading the footsteps of young, hopeful women from tenements to the factory. Next year, the colorful chalk will briefly reappear to quickly fade again, keeping memories of the tragedy alive. But the moment for a permanent monument honoring the 146 victims of the Triangle fire was long overdue.

The Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition and The Quest for a Permanent Memorial

Chalk was about to give birth to a new movement based not on impermanence, but one that would seek a permanent memorial allowing the victims of the Triangle factory to take their rightful place in New York City history. Contrasting a permanent memorial with the annual performance of Chalk, Sergel explains: “Its purpose is not only to commemorate but also to set terms about who counts in our culture and the legacy of the city’s past.”

The planning committee for the 2011 centennial of the Triangle fire grew directly from Chalk. Meeting at Judson Memorial Church, organizers were painfully aware of the Brown Building, the former site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, just blocks away.[9] Now owned by New York University, the building was the focus of annual commemorations of the Triangle fire. Organizers were determined to honor the dead with a permanent and dignified memorial at the Brown Building.

The committee began to lay plans to frame the centennial as a collective act of memory and resistance. Among those centennial organizers were a special group of stakeholders—those who had lost family members in the Triangle fire. It was membership in an exclusive club whose dues were pain and sorrow that had passed through generations. The victims were long gone, but their memory remained, seared onto the souls of their families by the flames of the fire.

Suzanne Pred Bass had two great aunts working on the ninth floor of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on March 25, 1911. Katie Wiener, age 17, survived by swinging herself onto the thick cable of the last descending elevator. She was the last person to leave the ninth floor alive. Her older sister Rosie Weiner, age 19, perished in the flames. Their brother, David, had confronted Triangle factory owners Harris and Blanck just moments after a jury found them not guilty in the deaths of the workers. “Murderers! Not guilty?! Where is the justice?” he had shouted at the pair before collapsing on the sidewalk in grief. [10]

Each year, commemorations for the victims had unfolded at the Brown Building, but the quest for a permanent memorial had been elusive. In 2008, the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition was born. The Coalition would spearhead the building of a public art memorial to honor the legacy of the Triangle factory workers. Suzanne Pred Bass explains, “The Coalition provides a base from which action can generate hope and change. What I did not anticipate was the showering of support across the board, from over 200 groups from this country and around the world.”

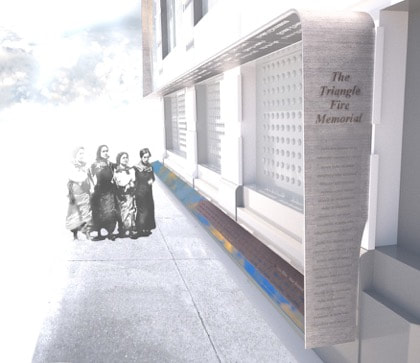

The plans for a permanent public memorial at the Brown Building began. Coalition members wanted both contemplation and participation to be expressed in the design. Much of the debate about the memorial revolved around the list of the dead. Some felt this was the key to the monument, while others feared a lack of emotional engagement would result by including such a list. A consensus concluded that the names be included in an emotionally compelling and integrated manner. All agreed that the selection of the final design must be beyond reproach. There must be a juried, blind process of review for the design excluding family and Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition members.

A jury headed by Deborah Berke, Dean of Yale School of Architecture, reviewed 170 entries from 30 countries. The winning selection, Reframing the Sky, was submitted by Richard Joon Yoo and Uri Wegman, both living in Queens at the time. Their design might be compared to the sewing of shirtwaists, requiring piecing together, cutting and embellishing to reach its final form. The monument names the victims at sidewalk level causing visitors to look down, and encourages visitors to look up by means of a twisting steel element evoking the mourning ribbons that once decorated the doorways of the dead. This series of gestures repeats and resonates with those of helpless onlookers who on March 25, 1911, watched the bodies of young women plunge to the sidewalks in a bid to escape the flames of the Triangle fire.

In keeping with the desire of the Coalition to include public acts of resistance and protest, Yoo and Wegman devised a public event for the construction of the steel ribbon feature of the monument. A Collective Ribbon was a two-day event hosted by Fashion Institute of Technology on March 16th and 17th, 2019. Participants in A Collective Ribbon contributed individual pieces of fabric, along with a story about the meaning of the fabric or the Triangle fire. The fabric pieces will be joined together and cast in metal, forming the textured steel ribbon that will reach down 100 feet from the ninth floor of the Brown Building.

The metal ribbon will split into two bands at the cornice above the first floor. Here, the ribbon joins angled bands on the eastern and southern facades of the building, into which the names of the 146 victims are cut. These end in a darkened reflective panel bearing a single line of text taken from eye witness accounts and testimonies of survivors. Above the text, the names of the victims are reflected from the angled bands.

Explains designer Richard Joon Yoo: “Reading the names of the victims as reflections in the sky is an essential part of the design, inviting the passerby to enter a space of literal and emotional reflection. The pedestrian, looking downward to the reflective panel, then looking upward, towards the trajectory of the ribbon, is part of the innate language of New York, and echoes the witnessing of the fire itself: looking up, looking down.”

How Much is the Triangle Fire Memorial Worth to New York City?

“We hope to have the unveiling of the completed monument on March 25, 2020,” says Mary Anne Trasciatti, President of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition. That completion date, the 109th anniversary of the Triangle fire, will depend upon the ability of the Coalition to raise funds.[11]

Governor Andrew Cuomo has pledged $1.5 million to fund the project’s full capital budget covering the fabrication, installation and permits of the memorial.[12] The Coalition now needs to raise money to cover ten years of upkeep before fabrication can begin.“We are building a public monument on a privately-owned building,” Trasciatti explains. The Brown Building, site of the 1911 fire, is now the property of New York University. The figures for upkeep range from $850,000.00 to $1.5 million. The Coalition is hoping to raise the remainder of the money from labor organizations, the fashion industry, and other stakeholders.[13]

The legacy of the 146 victims of the Triangle fire contributed directly to changes in New York labor laws, making them a model for the nation. Today, New York City is arguably one of the most pro-union cities in the country. But construction of a monument marking the event described as “the turning point in American labor laws” is hanging in the balance. Says Trasciatti: “Small towns in southern Italy have honored the Triangle fire victims by dedicating streets or a piazza to the memory of those victims who left Italy to immigrate to America. We need a Triangle memorial in New York City now.”

As Trasciatti warms to her subject, her tone becomes urgent: “We need a poignant, powerful work of art that draws people to the site and calls out to casual passersby, “Hey! A terrible thing happened here on March 25, 1911. One hundred forty-six people died. And you should know about it.”

Memorialization and the Legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Victims

The 146 victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire stand at the center of one of our country’s most tragic stories. But theirs is also a story of triumph in which poor, uneducated workers have become movers and shakers in our city. Theirs is a legacy that made New York labor laws into a model for the country, impacting thousands of lives for the better. It is an achievement accomplished through their quest for the American dream as well as their flesh and blood.

The efforts by today’s New York women to honor the Triangle factory dead, speak as much to the victims’ tragic deaths as the fantastic legacy they have given us. The current efforts to memorialize these 146 New Yorkers speak to the creative and political forces that characterize both struggling immigrant women at the turn of the century as well as their educated American descendants. New Yorkers all, they have lent their ideas, their passion and their work to create unique and moving memorials that mark our city today. They will show generations of New Yorkers to come, the spirit that makes New York the “City of Dreams.”

Kim Dramer is a retired professor of Art History at Fordham University. She has previously written for the Huffington Post and Untapped Cities as well as her own blog, New York Women.

Notes

[1] Author David von Drehle reports that by the turn of the 20th century, more New York immigrants worked in clothing factories than in any other business. The industry was doubling in size every decade. By 1909, more people worked in the factories of Manhattan than in all the mills and plants of Massachusetts, and by far the largest number were employed by the garment industry. The Triangle factory’s shipping plant bundled, boxed and dispersed 2,000 garments every day. Von Drehle, David (2003). The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

[2] On March 25, 1961, former United States Secretary of Labor (1933-1945), Frances Perkins dedicated a plaque to the victims on the corner of the Brown Building at Washington Place and Greene Street. It was the first permanent memorial to the victims in the half century since the tragedy. Perkins had spent decades fighting for laws to protect the American worker after witnessing the Triangle fire.

[3] Co-Commission with Cal Performances at the University of California, Berkeley; the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; and the University Musical Society of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[4] Remarks delivered during “Fire in my mouth – Remembering the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire,” Insights at the Atrium, at the David Rubinstein Atrium. Speakers Chana Pollack, Ruth Sergel and Julia Wolfe; Moderator Deborah Borda, January 15, 2019. Insights at the Atrium are co-presented with Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

[5] The Crossing, Donald Nally Artistic Director; Young People’s Chorus of New York City, Francisco J. Núñez Director.

[6] David von Drehle states that roughly 18,000 immigrants per month poured in New York City around this time. Von Drehle, David (2003). Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly.

[7] The list in von Drehle’s 2003 book identified 140 victims. The six missing victims were finally identified by amateur historian and genealogist, Michael Hirsch. It took Hirsch nearly four years of research using English, Yiddish and Italian language newspapers to change anonymous victims into known victimswith stories to tell.

[8] Sergel documents her pursuit of social justice for the victims of the Triangle fire and elsewhere in her 2016 book, See You in the Streets: Art, Action, and Remembering the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Iowa: University of Iowa Press. The book won the 2017 American Book Award Winner from the Before Columbus Foundation.

[9] The Brown Building is a 10-story building located at 23-29 Washington Place between Greene Street and Washington Square East. Built in 1899-1900 by Joseph Asch and Ole Olsen, the building was originally known as the Asch Building. A steel-framed high rise of ten stories, the building was dubbed a “loft” skyscraper in which many factories could be housed. The large, open rooms allowed long rows of sewing machines to be attached to a single electric motor by means of a drive shaft and flywheels. In 1929, Frederick Brown donated the building to New York University. It is known today as the Brown Building. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was located on the 8th, 9th and 10th floors of the building. Today, those floors house the Biology and Chemistry departments of New York University.

[10] David Wiener confronted the factory owners as they departed the courtroom via the prisoners’ pen to avoid the angry crowd. Fearing their waiting limousine would be an obvious target, the pair ducked into the nearest subway station as Weiner continued his cry. “We will get you yet,” he shouted before collapsing on the sidewalk. The next day, newspapers reported that the young man had been hospitalized “suffering from a disordered mind.” Cited in von Drehle, (2003).Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

[11] Telephone communication with the author, February 20, 2019.

[12] Depending on the amount needed for maintenance, Cuomo’s grant will cover half to two thirds of the total cost of the monument.

[13] Given the significance of the Triangle fire in New York City history, the costs of the memorial are relatively inexpensive. The Eleanor Roosevelt Memorial (1996) in Riverside Park cost $1.65 million in 2012 dollars. It was originally projected to cost $1.2 million in 2012 dollars. The memorial has an endowment to cover damage and maintenance. The Irish Hunger Memorial (2002) in Battery Park City cost over $5 million and then required an additional $2.5 million for repairs. The Harriet Tubman Memorial (2008) in Harlem cost $2.3 million in 2012 dollars.