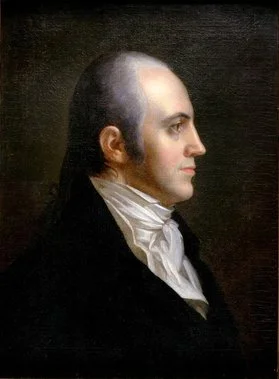

Myth #3: Aaron Burr

By Gerard Koeppel with Jason M. Barr

The Manhattan Street Grid Plan: Misconceptions and Corrections (a blog series)

It could be said that Aaron Burr, the baddest boy of early American democracy, is responsible for the famous Manhattan street grid. In a backhanded way — a way he surely would appreciate — he is.

But, like a perverse Madame de Pompadour, the deluge of orderly streets came after him, entirely without his input while he was laying low in Europe.

It happened this way. In 1802, the government of rapidly expanding New York City was looking to replace what served as its shabby city hall (a much-repurposed hundred-year-old building on Wall Street) with a proper, purpose-built structure equal to the city’s rising prospects and national reputation. A design competition ensued, bringing two dozen entries. Two stood out: the first, by sophisticated French exile Joseph Francois Mangin with local John McComb, Jr.; the second, by young British-born, Philadelphia-based architect Benjamin Latrobe, already on his way to becoming the so-called “Father of American Architecture.” The sponsor of Latrobe’s entry calculated that a design win that would induce Latrobe to relocate to New York. After the entry drawings were submitted, Latrobe’s well-connected sponsor guaranteed him that the votes of the Common (now City) Council were in the bag.

But he was wrong. In October 1802, the Council chose the Mangin-McComb plan. The graceful Louis XVI neoclassical building — entirely the design of Mangin, as McComb knew nothing French — has now entered its third century as the locus of city government. Latrobe, incensed, vowed never to design a New York building, much less move there. His sponsor vowed revenge. And Aaron Burr, then serving as the nation’s vice president, was adept at revenge.

The Mangin-McComb Plan

Burr’s opportunity came a few months later. Since 1797, Mangin had been employed by the Common Council to produce an accurate map of the city. His partner in that endeavor was Casimir Goerck, whose 1796 Common Lands plan, as we’ve already learned, eventually provided the fallback for the dawdling commissioners who announced their grid in 1811. The Mangin-Goerck partnership came to a premature end in 1798 when Goerck was among the two thousand New Yorkers — one in thirty — to die in the city’s worst of many yellow fever epidemics.

Mangin pressed on alone, determined to make “not the plan of the City such as it is,” as he was hired to do, but “as it is to be” — that is, as he believed it should be. As his plan evolved into the early 1800s, that meant cleaning up the jumble of crooked, narrow streets in the city proper; widening the island’s narrow southern tip by adding new orderly streets on landfill; and mapping out how the city should develop beyond its settled limits at Chambers Street (at the backside of where the new city hall would be), all the way up to what are now the lower East 20s. Mangin envisioned an array of rectilinear grids proceeding from different baselines and moving up the island and beyond the bounds of his map. Some of his grid sections had short and wide streets, others narrow and longer streets. The many irregular intersections of merging grids created numerous open, irregular spaces, well suited for small parks, important buildings, or other civic ornament. It was European urbanity adapted to a narrow island.

When Mangin’s plan (formally and generously known as the Mangin-Goerck Plan) was finally engraved and presented to the Common Council in February 1803, the Council, after some surprise, officially embraced it as “the new map of the city.” To be sure, there were issues with it, especially in the settled portions of the city where Mangin’s streets conflicted with the actual situation on the ground. But there was a sense that Mangin had produced what he had intended: not a map of the muddled city as it precisely was, but a plan of how it should be. In fact, the first plan ever conjured for the city’s future growth.

But the Mangin plan is not the founding document of modern physical Manhattan. By November 1803 it was formally rejected by the Common Council that had embraced it months earlier. Unsold copies (Mangin and the city were to share in profits) were destroyed. Owned copies were ordered returned, to be affixed with a label that said, in essence, that the map was a fantasy. The Mangin map was quickly forgotten. Only a few copies exist today.

The person most evidently responsible for this stunning turnabout was one Dr. Joseph Browne, Jr., a French-born surgeon who had served with distinction on the right side in the Revolution. In 1803, he happened to be the city’s Street Commissioner, then a relatively minor position that mostly entailed saying yes to whatever streets private landowners decided to lay through their lands because the modest city government rarely laid streets on it own. Yet, with Mangin’s map, Browne took a perversely active role in destroying it. Relentlessly pointing out its many inaccuracies — which no one denied because it was more valued as a future plan than an accurate map — Browne succeeded in winning the Common Council’s about-face on the map, and its ultimate passage into relative obscurity.

What had gotten Browne, who generally cared little for his street duties, so hepped up on trashing the Mangin plan? Not what, but who. That would be Browne’s domineering brother-in-law. Back in the dwindling days of the Revolution, a double-ring ceremony had joined two widowed half-sisters, Cathy De Visme and Theodosia Prevost to, respectively, Joseph Browne and, that’s right, Aaron Burr. Browne was immediately and forever in thrall to his formidable brother-in-law. Eventually ruined by his participation in Burr’s notorious western land adventures of 1805-06, Browne died abandoned and broke in frontier St. Louis in 1810 (while Burr took a four-year European breather from treason charges over his land conspiracy and lingering ill-feeling over his fatal 1804 duel with Alexander Hamilton).

In 1803, it was Browne’s task to avenge Burr’s perceived humiliation over his 1802 City Hall loss. There is no smoking gun here— Burr was a master of hidden agendas and dead-end paper trails — but suffice to say, Browne could have cared less about Mangin’s map while Burr cared greatly about avenging Mangin’s City Hall win. By 1803, Burr through direct and indirect actions and with the influential power of the vice presidency had come to dominate city government, the appointment of surgeon Browne as eminently unqualified street commissioner being one of many examples.

As with most Burr actions, short-term results that benefited him trumped long-range thinking of wider benefit. With Mangin’s inspired plan suddenly trashed in late 1803, the city found itself without the orderly future development plan that Mangin’s plan had promised. For the next three years, the overmatched city government tried to develop its own plan or invite others to offer one, with no success. Finally, unsettled by visions of what might have been, the city in early 1807 allowed the empowering of a commission to come up with whatever plan it wanted. As we’ve already learned, that deeply distracted commission did nothing more than smother the island with a bloated version of the Common Lands plan of Mangin’s dead partner Goerck.

Gerard Koeppel is the author of City on a Grid: How New York Became New York, Water for Gotham: A History, and Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire. Jason M. Barr is an Associate Professor of Economics at Rutgers University-Newark, and the author most recently of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers.