Foiling Attempted Kidnappings in Antebellum New York

By David Fiske

The Oscar-winning film 12 Years a Slave shocked audiences a few years ago — not just with its depiction of the cruelty often endured by slaves — but also because of its acknowledgement of a tragic historical reality: that in those days a free-born African American could be kidnapped and enslaved. Sadly, the story told by the film — of Solomon Northup’s kidnapping and subsequent servitude — was not a story that was unique. Before the Civil War, kidnapping was conducted with a certain degree of regularity.

Northup was kidnapped from a community in upstate New York — as were several other black citizens — but because there was a more substantial population of free blacks in New York City, the metropolis was the locale for a number of similar kidnappings.

In the city, law enforcement officers investigated a number of such crimes. In at least two cases, policemen from New York went undercover to apprehend criminals who attempted to lure African Americans out of the city and into a life of servitude. In these two cases, police were able to save the victims from a horrible fate.

Kidnappers knew that physical abductions could be messy. Any resistance offered by victims might draw the attention of bystanders, or even police. Instead, as with Northup, they commonly lured their victims away from the safety of home with promises of employment elsewhere.

David Ruggles (1810-1849), an abolitionist and journalist, who often raised awareness of free black New Yorkers' vulnerability to kidnapping.

In November 1819, Mary Underhill met a man named Joseph Pulford, who said he could get her a good-paying position if she were willing to relocate. Underhill, who was a servant in a home on Franklin Street in New York, said she would be interested, and Pulford told her to “keep dark and say nothing.” He said she should pack her things and meet him in a few days, after he’d made arrangements for her departure.

Actually, Pulford intended to sell her to a Captain Glasshune, the master of a ship bound for Havana. Having been approached by Pulford, Glasshune pretended to be interested in such a transaction. However, he instead told a man named Henry J. Hassey, who in turn alerted a constable named John C. Gillen. Gillen hatched a plan to catch Pulford.

Ms. Underhill showed up — per Pulford’s instructions — and he had her wait near the docks until he could find Captain Glasshune. When he met up with Glasshune, the captain was with another man named Johnson (who was actually Constable Gillen). Johnson claimed to be from Havana and was interested in obtaining two more black people to the 40 he said he already had on the ship. Pulford offered to sell Underhill, whom he said was waiting nearby, for $50. Johnson asked to see her first, not wanting to, as he said, buy “a pig in the poke.” After a short argument, Pulford led the way to where his victim was waiting. When asked to give a receipt for the $50 he was getting, Pulford protested, at which point “Johnson” revealed his true identity and told Pulford: “You must go along with me.” Pulford at first thought it was a joke, but was soon taken, along with Underhill, to the police station.

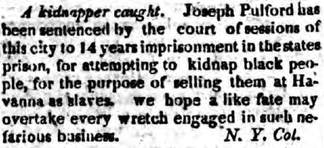

At a trial in December 1819, in which Mayor Cadwallader D. Colden presided, Underfill provided testimony that Colden called “unimpeachable.” Her story was backed up by Hassey and Gillen, who appeared as witnesses. Pulford argued that he had not forcibly seized the woman, nor taken her against her will. But New York State law included “inveigling” in its law against kidnapping. Inveigling, or tricking someone, still constituted an offense. As Colden informed the jury: “To constitute kidnapping or inveigling, no force is necessary.” Colden, who had antislavery leanings himself, dutifully told the jury that they must not allow their personal feelings on the matter to influence their deliberation. The jury quickly returned a guilty verdict, and Colden at once sentenced Pulford to the maximum allowed sentence: fourteen years in state prison. He regretted, he told the defendant, that he could not impose a death penalty.

The Colored American's coverage of the Pulford trial, 1819

In another case, years later, Sarah Taylor (who was also known as Sarah Harrison) resided with her mother on Grand Street in New York. In March 1858, a man by the name of James P. Finley convinced the teenager’s mother to let him take her over to Newark, New Jersey, where he knew of someone who was in need of a servant girl. Finley took her out of the city on a train, but instead of getting off at Newark, they continued on to Washington, D. C. There, Finley and a female acquaintance made attempts to sell the young girl to a slave trader. Ms. Taylor, however, figured out what was going on, and “made so much trouble about it” that her two kidnappers decided to scram, and went to Maryland.

Taylor was left at Willard’s hotel in Washington, and the proprietor sent a wire to Daniel F. Tiemann, the mayor of New York. Tiemann verified the girl’s story with her mother, and requested that Willard keep her at his hotel until some city policemen could get there. Not long afterward, Officers Barry and Lusk arrived and determined that the kidnappers were staying in Ellicott’s Mills, Maryland. There, Barry borrowed a postman’s uniform and pretended to be a postal clerk. When Finley came to collect his mail, Barry trailed him to a hotel, where he also found the female accomplice. The couple were taken into custody and returned to New York. Sarah Taylor was soon reunited with her family there.

During the prosecution of the perpetrators, two well-known antislavery activists were present: Lewis Tappan and Dr. James McCune Smith (the latter paid the bond that was required to insure that Taylor would appear as a witness at the trial). City Recorder George G. Barnard presided at the trial that spring. Finley was found guilty and sentenced to only two years in prison. He did not serve even that minimal sentence, however, as Governor Edwin D. Morgan pardoned him in January 1859, with the requirement that he return to his native Canada. The fate of the woman who assisted Finley is uncertain.

David Fiske is a librarian and researcher. He is the author of Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave and Solomon Northup's Kindred: The Kidnapping of Free Citizens before the Civil War.

Further reading:

The attempted kidnapping of Mary Underhill is described in “Joseph Pulford’s Case,” New-York City-Hall Recorder, for the Year 1819 (Daniel Rogers, compiler), pp. 172-174.

Sarah Taylor's kidnapping was reported in various newspapers in New York City and Washington, D. C. in the spring of 1858. A reasonably detailed account appeared in the New York Times on March 25, 1858.