“Eternal Vigilance is the Price of Liberty”: Resistance to Segregated Seating in New York City’s Theaters

By Alyssa Lopez

In 1924, Walter White, the assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), sent a letter of warning to several New York City-based black newspapers. “There have been... numerous complaints regarding the denial to colored people,” he explained, “of service in various places of public accommodations,” especially theaters on 125th Street, Harlem’s main thoroughfare. Urging the editors to reprint the state’s civil rights statute in their papers whenever possible, White warned that “it seems that there is a definite campaign being carried out in New York City to limit the civil rights of colored people.”[1] While White was bringing this issue to journalists’ attention in 1924, discriminatory seating policies in the city’s theaters were more than common and certainly predated White’s distressed letter, stretching from the 19th century into the first half of the 20th century and beyond the boundaries of Harlem.

In 1873, New York had been one of the first states in the nation to enact civil rights legislation, which stipulated that “no citizen of this state shall, by reason of race, color or previous condition of servitude” be denied “full and equal enjoyment” of places of amusement, including “theatres.” City and state courts were inundated with civil rights cases, many of which included black patrons who were refused admission entirely or who were denied seating in the orchestra section. When “motion picture houses” were expressly added in a 1918 expansion of the bill, discrimination in these spaces mirrored existing patterns.[2] Despite the ubiquitous discrimination they faced, New York City’s black theatergoers did not allow these blatant and unabashed violations of the law to go unchallenged. Publicly and privately, they confronted theater owners, managers, and employees in defense of their rights as citizens and human beings, demanding equal access to the city’s amusements and fair treatment throughout the city.

As White’s letters make clear, New York City’s black press played a significant role in keeping its readers abreast of various civil rights struggles locally and nationally, including those that occurred within the city’s theaters. Almost two decades earlier, in 1909, the New York Age shed its previously “lax and negligent” attitude after a black patron won a suit against a sightseeing company, vowing instead to “call attention” to violations of the state’s civil rights law. “The date is far too late,” the article cried, “for respectable colored men and women to be humiliated in public spaces … Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty!”[3] The Age and other black weeklies in New York and throughout the country did not fail to live up to this mission, sustaining its role as a “potent force for social change” in a deeply segregated society.[4] As such, the Age and New York Amsterdam News, both with widespread black readership, reported frequently on discriminatory theaters throughout the city, transforming various individual struggles into very public community battles.[5]

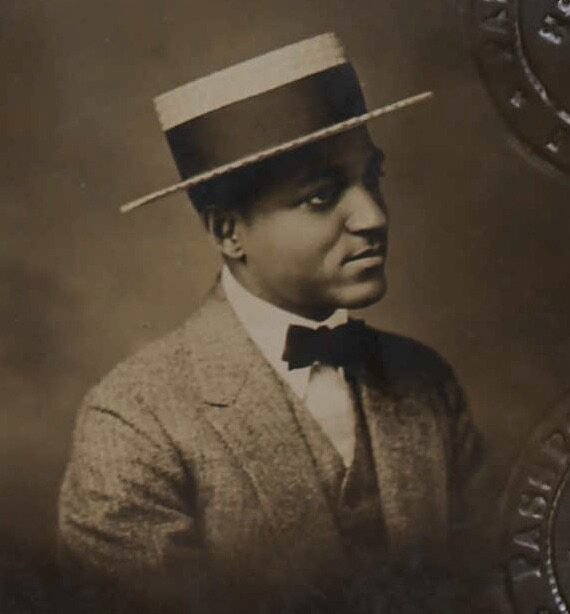

Lester Walton, Dramatic Editor of the New York Age

The same year that the Age promised more consistent reporting of discrimination against black New Yorkers in public spaces, Lester Walton, the paper’s dramatic editor, dedicated an entire article to lambasting local theater managers for segregated seating. When in conversation with one white theater manager at the Majestic, who referred to segregated seating as a “deplorable condition which... could not be helped” and insisted that “colored theatergoers should not try to go where they are not wanted,” Walton quipped that “the Negro race was [not] put on earth to conform with every wish and desire of the Caucasian.” Framing the fight against segregated seating as a basic individual right, Walton continued, “The fact that it was presumed that we were not wanted did not necessarily mean that we should not aspire to make an effort to realize our ambition.” “We do want to walk about,” he stressed, “with a feeling of pride and self-esteem, knowing full well that it is your prerogative to sit wherever you desire.” But Walton also positioned the desire to sit in orchestra seats instead of the balcony as a right afforded black theatergoers by law. “What is particularly galling to us,” he insisted, “is the thought that we who are native-born American citizens are discriminated against solely on account of color, and that an organized effort is being made to deprive us of rights and privileges to which we are justly entitled by law.”[6] Simply put, Walton considered segregated seating a violation of black theatergoers dignity and their rights as New Yorkers and American citizens. The black press utilized this framework to appeal to readers facing discrimination and, primarily, to entice and incite legal action against discriminatory theaters.

Take for example, the cases of Dr. and Mrs. Roberts. In 1911, the couple fell victim to the typical pattern of discrimination in New York City’s theaters. They purchased orchestra tickets in hopes of getting a decent view of the mixed bill of vaudeville and motion pictures, but when they went to take their seats in that area, ushers quickly tried to whisk them away to the balcony. Even when they refused, theater employees demanded they change seats or leave the theater and get a refund. When the Robertses expressly refused, the police were called. Instead of protecting the Robertses, whose rights were being violated, an officer threatened them, explaining “that unless they left the first floor as the manager had requested he would be compelled to arrest them.”

In his reporting of the incident, Walton deliberately emphasized the respectability of the couple. He noted that Mr. Roberts was “one of the leading colored dentists in New York City,” and included professional portraits of the couple throughout his column. The one of Mrs. Roberts, in which she gracefully looks off camera, her hair tied back with a delicate white lace ribbon, is neatly aligned with the paragraph in which the manager claimed the couple was asked to move because of “boisterous” behavior. In asserting the couple’s status — as married, professional, and middle class — Walton challenged the narrative of black inferiority, effectively flipping the script on racist defenses of segregated seating. “Instead of spending their time telling their friends and acquaintances of the humiliation to which they were submitted,” Walton exalted, “they availed themselves of the opportunity afforded all citizens of color in New York and aired their differences in court.” Rather than “showing their resentment in talk! talk! talk!” Dr. and Mr. Roberts took action and their case was represented by Walton as one to be replicated throughout the city.[7]

Still, it was not until the 1920s that a concerted resistance to segregated seating emerged throughout the city, fueled by hundreds of articles in local black newspapers. In them, authors publicly shamed white theater employees and shifted the burden of humiliation in these incidents from black theatergoers to the establishments that broke the law. The Loew’s circuit, a chain of theaters throughout much of the city, was a common target of journalists and the ordinary people who recounted their stories to the press. Though Walter White’s 1924 letter did not specify any particular theaters, the NAACP had been fielding letters of complaint about Loew’s theaters for years. In 1921, James Weldon Johnson, secretary of the NAACP, reached out to Marcus Loew about “a number of complaints... regarding certain employees at Loew Theatres” who refused black patrons orchestra tickets.[8] Though the circuit’s formal response — “We are thoroughly aware of the Civil Rights Law” — suggests an acknowledgement of black theatergoers’ rights, discriminatory incidents continued, with complaints against the theaters often reaching the city’s black press with extraordinary detail on the incident and people involved.[9]

After a series of violations at the Loew’s Victoria Theatre in Harlem, one editorial theorized that “the Negro does not take readily to ‘black hand’ tactics in resenting insult to his race... if he did Loew’s Victoria Theatre would some fine morning find itself a heap of ruins from a bomb or torch.”[10] Loew’s American Theatre, located in midtown, was sued by two Harlem residents in 1925 after they were totally refused admission to the theater. Three years later that same theater came under fire again when Mrs. Strickland, a black elementary school teacher, and her husband, a postal worker, were denied the orchestra seats they paid for. In the letter she sent to the New York Age describing the incident, Mrs. Strickland wrote, “If this is the way this chain of theatres feels toward us then we should not enrich their coffers... but rather go where… we are assured of the justice, equality and respect that is justly due us as American citizens.”[11] Though not submitted to the press, one complainant sent a letter to Mayor Walker about the humiliation that discrimination entails: “It would be more honest to the Colored people to place a sign in the box office with lettering… ‘NO COLORED PEOPLE ALLOWED IN THE ORCHESTRA OF THIS THEATRE’,” he suggested, “with such a sign the Colored people would feel less embarrassed.”[12] Like Walton’s journalism over a decade earlier, these black theatergoers called public attention to their shame and indignation in service of change. They wrote with the express purpose of reversing the direction of that shame, placing the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of those white theater employees who broke the law and used the flimsy pretext of custom and behavior in order to treat black theatergoers as less than.

Loew’s Victoria Theatre in Harlem

Beyond Manhattan, the Loew’s circuit continued its discriminatory policies, while activists remained persistent in their challenges. Between 1926-1927, the Bedford Theatre in Brooklyn was targeted by a local branch of the NAACP devoted to “checking theater segregation” after “numerous complaints had poured” into the organization’s offices.[13] The president of the Jamaica branch of the NAACP, Charles Reid, prepared himself and the organization’s members “for the big battle which looms in the fight against theatre discrimination,” forming a special committee to fight the practice of segregated seating. Reid offered strong words for those theaters in the area that segregated black theatergoers: “We are going to refuse to be herded into any general section of any theatre like cattle at the whim of some cheap and unprincipled theatre manager.”[14] Though it’s unclear if the exchange was successful in ending discriminatory seating at the theater, Reid’s committee did hold a meeting with the manager at Loew’s Valencia, who claimed it was not the theater’s policy to discriminate and he would talk with his employees.

Despite these and many other efforts to end segregated seating throughout the city’s theaters and in the face of its illegality, the practice continued for decades. By the end of World War II, the fight against discriminatory theaters became wrapped up in larger civil rights struggles throughout the city, including anti-discrimination enforcement in employment, education, and public accommodations across the board. Still, the editorials, letter-writing, and civil suits outlined here served as groundwork for later generations. They represent refusals to be treated unfairly and demands for recognition of humanity and citizenship. As such, their public remonstrations make manifest the ways that theaters were not just places of amusement, but also arenas for protest.

Alyssa Lopez is an Assistant Professor of History at Providence College and a contributing editor at Gotham.

[1] Letter from Walter White to Fred Moore, October 20, 1924, Papers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Part 11: Special Subject Files, 1912-1939, Series A. White sent the letter to the New York Age, the New York Amsterdam News, The Tattler, Harlem Home News, New York News, and the Chicago Defender.

[2] New York Laws of 1873, Chapter 186, Sec. 1.; Laws of the State of New York, 1918, Chapter 196, Sec. 40.

[3] “Discrimination in New York,” New York Age, January 21, 1909.

[4] Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909-1949 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), 2.

[5] In 1922, the Age and Amsterdam News held a collective circulation of about 50,000. While these numbers are small in comparison to other black weeklies like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier with nationwide circulation numbers in the 100,000 range, the papers remained important to black New Yorkers because of their emphasis on local news, information, and civil rights struggles.

[6] Lester Walton, “Negroes in New York Theatres,” New York Age, November 18, 1909.

[7] Lester Walton, “Theatre Manager Loses Case,” New York Age, November 2, 1911.

[8] Letter from James Weldon Johnson to Marcus Loew, November 30, 1921, Papers of the NAACP, Part 11: Special Subject Files, 1912-1939, Series A.

[9] Letter from Leopold Friedman to NAACP, December 5, 1921, Papers of the NAACP, Part 11: Special Subject Files, 1912-1939, Series A.

[10] “Discrimination Practised Under Our Noses,” New York Amsterdam News, June 23, 1926.

[11] “Loew’s Theatres Charged with Jim Crow Policy in Segregated Negro Patrons at American and Victoria,” New York Age, February 25, 1928.

[12] Letter from Jacob Brigman to James J. Walker, December 10, 1929, Papers of the NAACP, Part 11: Special Subject Files, 1912-1939, Series A.

[13] W. White and S.M. Douglas Address Mass Meeting Against Discrimination,” New York Amsterdam News, April 13, 1927.

[14] “Jamaica Branch NAACP Girding for Battle Against Discrimination,” New York Amsterdam News, December 31, 1930.