Brooklyn Is Expanding: Introductory Notes on a Global Borough

By Benjamin H. Shepard and Mark J. Noonan, with notes from Greg Smithsimon

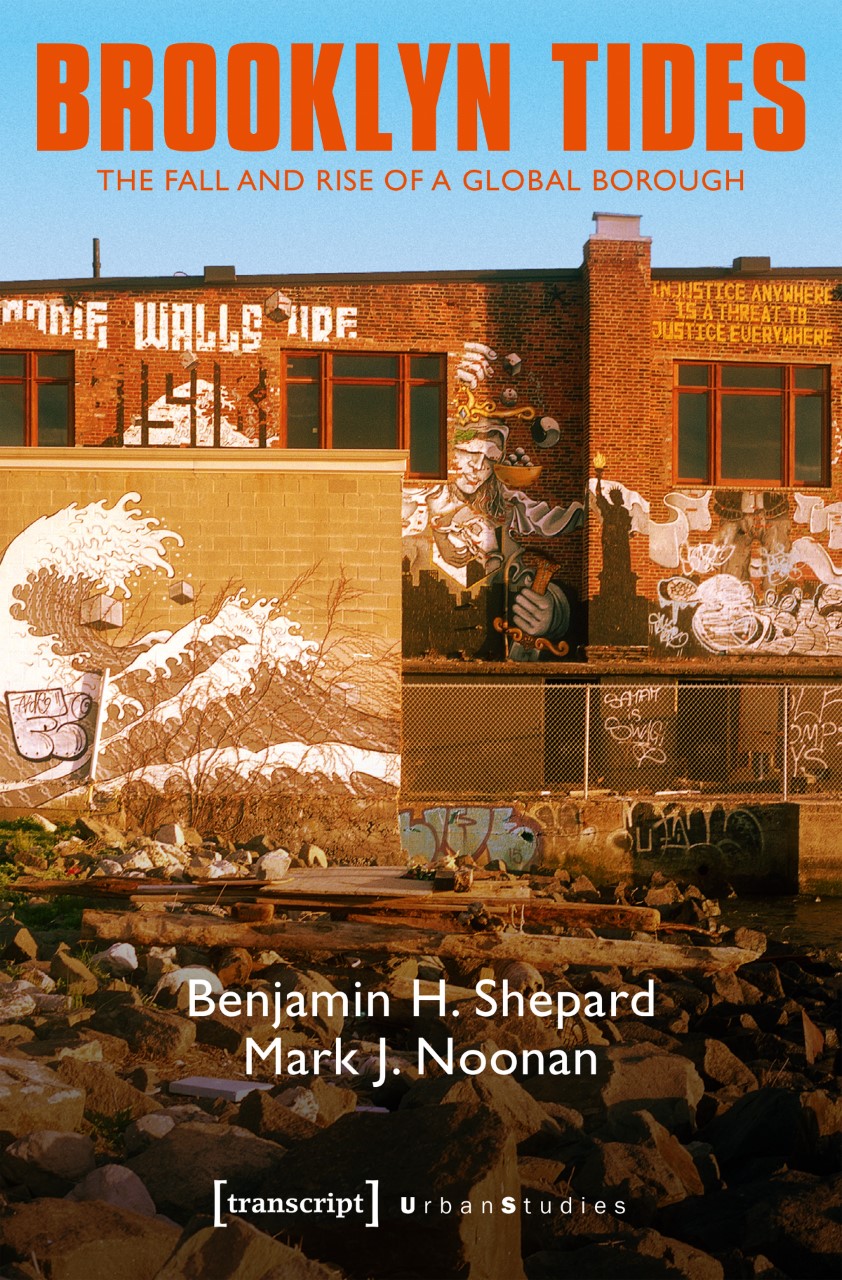

Brooklyn Tides: The Fall and Rise of a Global Borough

by Benjamin H. Shepard and Mark J. Noonan

Transcript-Verlag, June 2017

230 pages

This book concerns tides: tides of people, tides of development, tides of industry, tides of power, and tides of resistance. Brooklyn, once a city, then a borough, and now a brand, illustrates the tensions that arise between the local and the global in a given place. The ebb and flow of these dynamics can be witnessed on the street as well as in the many seminal books and films set in Brooklyn and concerned with its unique status as both a distinctive place and an ever-evolving imaginative space evoking a wide range of associations and emotions.

Hurried and whirling tides are what Brooklyn — “city of wharves and stores” — and Manhattan — “city of tall façades of marble and iron,” as Walt Whitman described them — have in common. At the same time, the city across the river has always felt like something very, very far away. Globalization and mercantilism, war and environmental change, have also felt like faraway notions. Nonetheless they were still felt. The incoming tides were, consequently, not always gleeful, for Brooklyn was often at the mercy of outside forces. The Dodgers were to depart in the 1950s in an example of what a global marketplace and local powerbrokers with alternate ambitions can do to a local space; this was only after the team had helped integrate baseball, offering a feel-good narrative replaced by a sense of emptiness which would last decades. From the nineteenth century into the twentieth, Brooklyn was always part of something larger, something global, with which it was both connected and seemingly disconnected, displacing residents like its beloved baseball team.

It was hard to expunge the feeling that the borough was seldom at the center of things. “When I was a child I thought we lived at the end of the world,” explains Alfred Kazin in his 1951 book, A Walker in the City. “It was the eternity of the subway ride into the city that first gave me this idea.” Brooklyn was almost all periphery. Like present-day Los Angeles, it seemed to go on forever, especially on the long subway ride he describes, from the East River, beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, past Borough Hall and Prospect Park, out to Canarsie. “We were of the city but somehow not in it,” he confesses. “We were at the end of the line. We were the children of immigrants who had cramped at the city’s back door, in New York’s rawest, remotest, cheapest ghetto, enclosed on one side by the Canarsie flats and on the other side by the hallowed middle-class districts that showed the way to New York.”

Kazin’s concerns about his life in the city are familiar to many. “The anxiety of our era has to do fundamentally with space,” argues Michel Foucault in his essay, “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias.” Spaces are not mere containers, even as they can sometimes entrap people when there are no doors for exit or entry. For Foucault, they are places involved with sets of relations that give them meaning. “In other words,” he writes, “we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things ... we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another... Our epoch is one in which space takes for us the form of relations among sites.” The “form of relations,” of which Foucault speaks, take shape through our interactions within the time we spend walking the streets, riding the subway, sitting on stoops, or hanging out in public space, where we make new friends and discover other spaces. It even takes shape within Brooklyn’s relationship with its Manhattan neighbor. Manhattan is most often considered a place for work, while Brooklyn is seen as a place of residence — though even this is changing.

The city is shaped by our interactions within these spaces, and the social relations amongst the tides of people filling them. Waves of people, economic systems, and stories shape the borough. Increasingly, Brooklyn is a place where difference finds space between bike rides, bridges, brownfields, block parties, foreclosure-defense street actions, communities of resistance, and community gardens created by and for the people here. Here we dance with marching bands, celebrate the legacies of Michael Jackson and Prince at Fort Greene Park, visit Coney Island, or simply hang out on Brooklyn’s lively streets and in its many watering holes and restaurants. Here, heterotopias take shape, day and night, through interactions with a mix of people across class and ethnic lines. These are spaces of otherness, with countless ebbs and tides between who’s coming and who’s going.

Flowing through this book are the stories of community gardeners, agitators, artists, students, and local residents trying to find a place to live, of those like Kazin, who felt on the outside, while contending with the clash of bodies and forces of the city “beyond.” They are the narratives of those lost on the subway. It is the Brooklyn which has long had to cope with alienation, low-wage jobs, inadequate housing, police violence, the possibility of deportation,

incarceration, and stop-and-frisk policing. As depicted in fictionalized stories such as A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Death of a Salesman, and Do the Right Thing, as well as in real life, Brooklyn is filled with those longing for greater respect and upward mobility. It is a very distinct local place. This is a place where global forces always seem to have the upper hand. But it is also a place where people organize and build their own commons. Here, communities rise and fall, and rise again. Instead of the same old thing, citizens have learned to ride the tides, forging their own distinctive livable globalized space.

Hovering over these conversations is the concern that it may all be too late. The condominiums popping up everywhere, skyrocketing rents, ugly buildings overlooking Brooklyn Bridge Park, rampant police abuses, hospital and independent bookstore closings lend credence to this conclusion. This specter of failure has always been a part of life here. General George Washington famously lost the Battle of Brooklyn, retreating into the fog rather than face British troops who outnumbered his. The events of August 27, 1776 have often been recognized as a moment of losing a battle but ultimately winning a war. Instead of following conventional rules of engagement, Washington led his troops west through the fog, past the marsh that would become the Gowanus Canal, to the East River, where they fled to safety. Sometimes you have to retreat and pick your battles. That is the story of this book, of battling titans, the British troops, even capitalism itself. You are not always going to win, but you are going to retreat, rope-a-dope, elude opponents, in the fight to preserve something truly special. We see it today in the streets of Brooklyn from Bed-Stuy to Prospect Park and Coney Island. This is a book about lots and lots of small battles that amount to large wins.

A Globalized Space

Scholarship on global cities has identified the distinctive roles that places like New York, Paris, Tokyo, London, Los Angeles, and Chicago play in the global economic system. However, most studies of the new role of these “global cities” focus on downtown, the financial district, the multinational financial institutions, and the white-collar employees who work there. Far less emphasis has been placed on the contributions of the large numbers of working-class immigrants and their transnational culture, the armies of service industry workers who sustain the financial industry and its executives, the reduced social contract working people are offered in the neoliberal global city, and the precariousness of this new economic order for most workers. Their experience propels Global Brooklyn.

Writing on global cities has rarely undertaken a sustained examination of the periphery of the global city, even though it makes up the vast majority of the city in terms of population, lived experience, and space. Global Brooklyn wakes the city up in the morning, provides the labor power that gets it through its day, and puts it to bed at night. Its diverse communities are also rich sources of global cultural production, even while residents face some of the most severe consequences of the neoliberal policies generated by the global city. On a day-to-day basis, its residents cope with a neoliberal political ideology that protects private property interests, drives down wages, advocates the privatization of social resources, and protests regulatory frameworks that hinder free market values. “[U]neven development inherent in neoliberal entrepreneurial economic development strategies favor…concentrated capital at the expense of the poor and middle classes,” notes Brooklyn sociologist Alex Vitale. Those on the margins of this global borough feel the squeeze, as inequality increases. Over and over again, the development of cities seems to mold a polarization, dividing classes, creating pockets of urban poor, who are

increasingly restricted. In a departure from previous studies, Brooklyn Tides considers globalism’s effects on these local populations, placing particular emphasis on the agency people have to act and challenge the structural constraints the global city imposes.

Brooklyn Tides addresses the question of what it means to live in a global city for the millions of residents who experience the benefits and costs on a daily basis. Is there the possibility of another type of urban experience in the glare of globalization? How do local people find space for autonomy while contending with the tides of neoliberal urbanism crashing in around them? These questions churn through this study of the ebbs and flows of Brooklyn’s tides. To answer these questions, we consider the literature and history of Brooklyn as well as the efforts of activists who have sought to have an impact on this space.

Along the way, we trace the workings of anti-gentrification activist Imani Henry, of cyclists Keegan Stephan and Monica Hunken, anti-consumer activist Reverend Billy (a.k.a. Bill Talen) and his Church of Stop Shopping, artists Robin Michals and José Parlá, as well as groups such as Right of Way, Public Space Party, Occupy, Equality Flatbush, and Transportation Alternatives to trace an alternative story of global Brooklyn. This book does not consider the struggles of every activist or campaign in this borough; rather it focuses on a small group of artists and activists taking on the challenges of the globalization churning through the streets of their neighborhoods. Through their efforts, each suggests that there are things everyone can do to create a livable city.

This is a vision of a just, sustainable city, supported by mutual aid and friendship, not high poverty rates and escalating cycles of police brutality to discipline the masses. Still, why study Brooklyn? Just as every global city has a business district, every global city has a Brooklyn. Whether they are called outer boroughs, banlieues, peripheries, suburbs, or shanty towns, these are the vast districts, much larger than the center-city home of power and wealth, which provide the labor for the global city. Just as each city’s downtown is different because of the individual roles each city plays in the global financial economy, so, of course, every “Brooklyn” is unique, shaped by its distinctive history, the residents’ responses to globalization’s demands, the particular composition of its immigrant communities, and the cultural production that takes place in each borough. While no book can do justice to every facet of globalization across this borough, Brooklyn Tides examines the stories of everyday residents of Brooklyn to understand some of the most significant features of New York’s most famous working-class, immigrant, and service-industry suburb.

Brooklyn has coped with the ravages of displacement and deindustrialization for decades. In its most desperate decade, over half a million people moved out of the borough. The borough lost tens of thousands of jobs. Between the infusions of financial capital, economic development, cultural redefinition, and accompanying homogenization, its neighborhoods were being remade in front of our eyes. Within the last decade, rapid gentrification has made parts of the borough sites of luxury living, work, and recreation. Today, its renovated waterways are being filled with high-rise condos. Much of this development is supported by the legacies of red-lining, foreclosures, police brutality, sky-rocketing rents, and hyper-policing of public space. In order to ensure this better business climate for urban growth and development, New York’s brand of urban neoliberalism has cultivated intricate public policies and policing approaches aimed at maximizing social control of public spaces, including closed-circuited video surveillance systems, anti-homeless laws, and gated communities.

Today, its citizens revel in the borough’s vast cultural resources but lament patterns of displacement and uneven development which follow such patterns of urban flux. While many newer residents bring affluence, for much of the borough New York’s fiscal crisis of the 1970’s never ended. The borough continues to endure persistent unemployment and loss of work for the lower and middle classes. The story of global Brooklyn also demonstrates the power of global capital and the processes of cultural erasure, as homogenization robs local spaces of their color.

As a global borough, Brooklyn contends with both cultural erasure and expansion. Like many urban geographies, Brooklyn’s public spaces, its waterways, its spaces for work and play, have become sites of contestation that seek to navigate lurching changes. After all, for much of the nineteenth century, Brooklyn was an agricultural community, transformed by the region’s industrial development in the postbellum period. As late as 1879, it provided much of the region’s vegetable production. Four decades later, little was left of this once flourishing agricultural economy or the rural communities it helped sustain. This history raises the question: is urban development an inevitable component of industrialization?

Could the agricultural base of Brooklyn’s past have survived the residential real estate development with some foresight? This is a question well worth asking. Brooklyn’s transformation from rural economy into a dense urban center took shape in response to both technological innovation and a seemingly blind faith in free markets which made farmland prohibitively expensive. Still, questions about costs and benefits, what was lost and gained from what Marc Linder and Lawrence Zacharias term "irrational deagriculturization" grip global Brooklyn. Any number of values were stifled when the borough paved over a once vibrant agricultural terrain. Facing a rapidly changing landscape, can this “agricultural dissolution” be reversed here? Some suggest the answer is affirmative. Urban farms are making a comeback in Brooklyn. The largest of these, Brooklyn Grange, produces over 40,000 lbs. of organically-grown vegetables, grown on rooftops in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. According to Paul Lightfoot, the chief executive of Bright Farms, “Brooklyn...has now become a local food scene second to none. We’re bringing a business model where food is grown and sold right in the community.”

For such initiatives to become a sustained reality, policy makers must support a host of progressive ideas, particularly the right to open space. Of course, such thinking challenges cities to question a dominant paradigm which views economic development and community needs as opposites.

They need not be. Others follow a different road along a seemingly unsustainable path toward hyper-development. Over the dozen years of the Bloomberg era here, space was rezoned — a third of the city — to make way for more sky-scrapers, gentrification, blandification, and inevitable displacement. And the process continues today.

Is it possible for this global borough to follow a path toward a more sustainable urbanism? This account of Brooklyn’s past and present insists that the future of the borough remains in the hands of the people who live here.

Benjamin Shepard is a Professor in the Human Services Department at City Tech, CUNY. He is the author of numerous books, including Sustainable Urbanism and Brooklyn Tides, co-authored with Mark Noonan. Join Brooklyn Tide's authors tonight for a panel discussion on the history and future of Brooklyn at Greenlight Bookstore at 7:30.

This post is an excerpt from the authors' new Brooklyn Tides: The Fall and Rise of a Global Borough, courtesy of Transcript-Verlag.