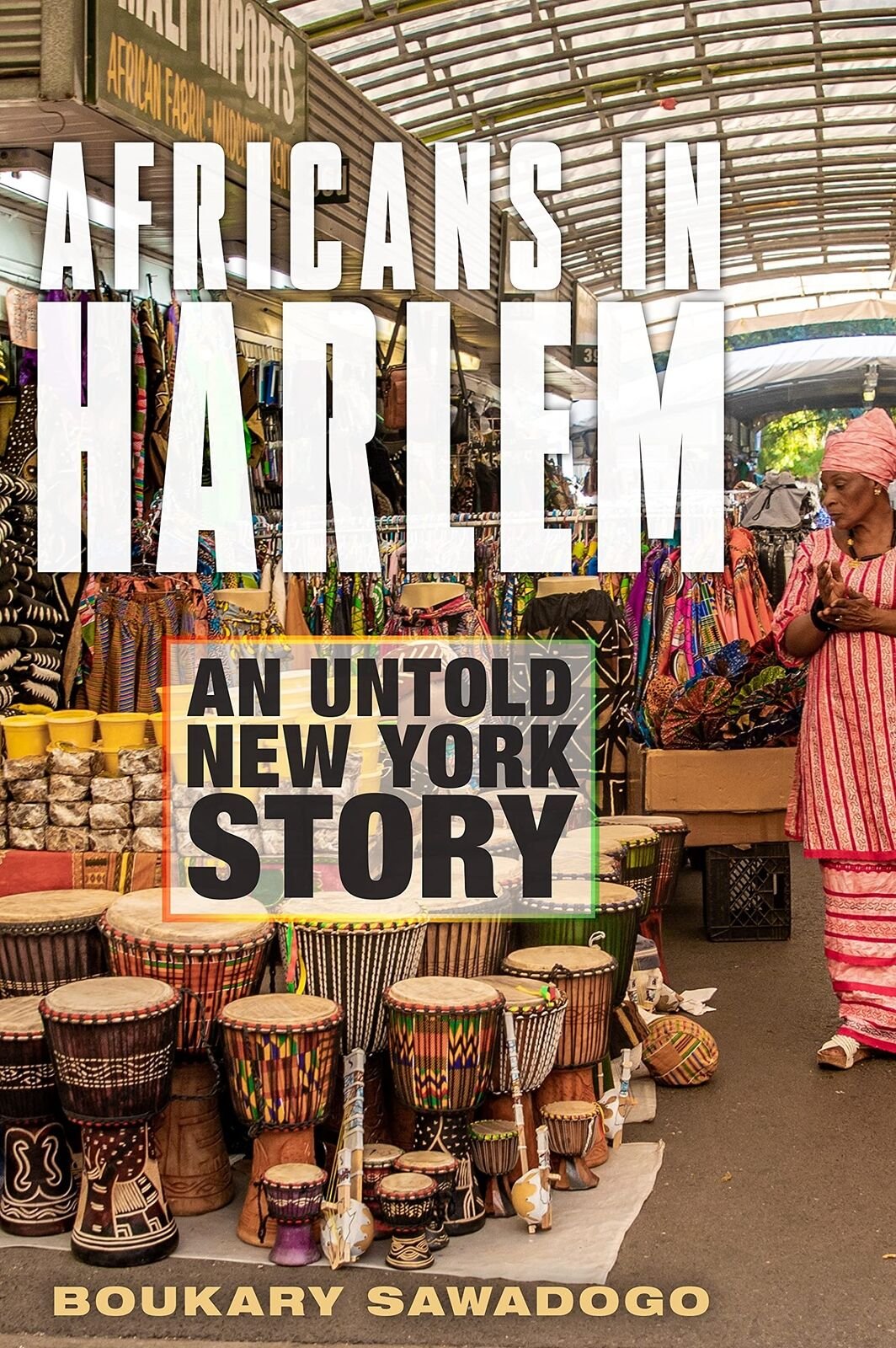

Africans in Harlem: An Untold New York Story

Reviewed by David O. Monda

Boukary Sawadogo’s book Africans in Harlem: An Untold New York Story resonated with me as an African migrant living in Harlem. From the introductory section, “Africa in Harlem,” to the conclusion of the last chapter, “Searching for Africa in the Diaspora,” the writer allowed me to understand the genesis, formation, and growth of this community.

Africans in Harlem: An Untold New York Story

By Boukary Sawadogo

Fordham University Press, Empire State Editions, 2022

224 pages

The book will mean different things to different readers. For students, it will develop a deeper understanding to Harlem. For the academic, it represents a fine interdisciplinary effort, piecing together many moving cogs, as it examines the political, cultural, economic, spatial, and anthropological roots of the migration. It will be a solid bridge to theoretical questions like class, with businesses, as well as places of worship and community centers, considered. For the casual reader, it will be a gem to keep and share as a major contribution in understanding African migration to New York generally, and Harlem in particular. In writing this manuscript, Boukary has filled a gaping hole in our understanding of a recent US immigrant group, encapsulating their lived experiences, while placing the untold African story in the ethos of New York, a global migrant city.

Boukary has done a wonderful job gathering data and oral histories from these migrants, highlighting several diverse groups, from the Burkinabe and the Senegalese to the Malians and Guineans. He uses a wealth of skill in interviewing that made reading the book interesting. He did well to keep himself as part of the story, too. His personal voice and experiences are prevalent throughout. His examination of the depictions of Africa in US cinema, the arts, and literature is particularly enlightening. And he does a fine job connecting radical black politics to the African awakening in the Cold War, and explaining the relations between Africans and African Americans in Harlem.

He is right in drawing in the African American experience as well. The foundational ethos of the African American experience in making conditions right for migrating Africans cannot be understated. But the challenge was in balancing this narrative with that of African migrants in Harlem. In attempting to get this balance right, something was lost in Boukary’s story. A nuanced explanation of the major African groups that came to Harlem would have been a more effective path. If the book is about Africans in Harlem, the reader expects it to be about Africans in Harlem.

In addressing the “push factors” to migration, for example, the political experiences between source countries could have been unpacked more deeply. The Senegalese, who faced economic deterioration but no history of military coup d’état, differs significantly from that of the Burkinabe, Malians, and Guineans, who experienced military rule and repressive authoritarianism. In particular, the stories of Francophone countries that fell into civil war, such as Cote d’Ivoire, would have been interesting to hear against the backdrop of the other factors Boukary emphasizes. Boukary instead delineates a critical debate around how much Francophone influence still defines the identity of Africans in global cities like New York, London, and Paris. Arguing that Francophone Africans abandoned association with their nations’ former colonial master as it grew more xenophobic in the 1970 – 80’s, he explains the move to the United States as driven by the soft power of Netflix, Hollywood, rap, and broader pop culture, as well as employment opportunities.

Geo-spatially, the nuances of the migration patterns could have been unpacked in more detail, too. For instance, why are the Burkinabe found in their area versus “Little Senegal.” Are there tensions in these new migrant spaces from the host communities, or between the different African migrant communities? If so, how are they resolved? A more detailed exploration of the differences between these groups would have been helpful.

Indeed, there are several spaces this monograph has opened up to further study and analysis. These are beyond the scope of Boukary’s book but are pertinent in understanding Africans in Harlem. For instance, it would be helpful to know how many Africans and African Americans intermarry. Are polygamous marriages tolerated in secret due to potential backlash from the dominant culture? How many couples are of Muslim faith compared with other faiths? Is there an LGBTQI+ African community in Harlem? How are those issues managed in the African, or African-American community? How severe is gentrification? How does it affect the African community?

In addition, I would be eager to learn how African businesses use their stores as locations for both commerce and cultural negotiation or exchange. How did African entrepreneurs start and develop their businesses in Harlem? With the challenge of Covid-19, how did they cope? What stress factors were created by the pandemic in the US and Africa? How did businessmen and entrepeneurs deal with the lockdowns and lack of remittances, or diaspora funds sent back home to Africa? Lastly, on immigration, what percentage of the African community in Harlem is legally documented? What percentage is not? How do Africans in Harlem support each other on this sensitive and problematic issue?

Still, Boukary’s book illuminates many areas of the African experience in Harlem. It is a book well worth reading, and a powerful addition to our understanding.

David O. Monda is an instructor of Political Science at the City University of New York's Guttman Community College. He researches migration policy in South Africa, immigration rights, human rights broadly defined.