Book Review: Mariah Adin, The Brooklyn Thrill-Kill Gang and the Great Comic Book Scare of the 1950s

Reviewed by Martin Lund

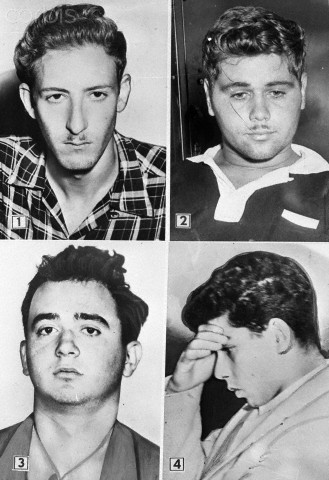

Historian Mariah Adin’s new book tackles the story of Brooklyn’s so-called “thrill-kill gang,” a well-publicized case in 1954 involving four young Jewish Americans arrested and tried in relation to the deaths of two men in August of that year. After the trial, anti-comics crusaders used the case to attempt to outlaw violent comics in the state of New York. As someone who has studied the history of Jews and comics and New York City for years, this book sounded like a match made in heaven.

Once I started reading it, however, I found myself frequently disappointed. None of the topics Adin promises to explore –- juvenile delinquency, New York’s Jewish community, the comic book scare –- are given much depth. Indeed, the book is largely descriptive. Although it suffers from a lack of editing and is often repetitive, the narrative of the crime and trial itself is told in an engaging way. Less engaging are the chapters that deal with theories about juvenile delinquency and the debate about the boys in the Jewish press. Adin presents common theories of the causes of juvenile delinquency in one chapter, which then drop from sight inthe rest of the book. And, with regards to the Jewish American response in New York, Adin limits her discussion to citing only a single Jewish newspaper: the Forward. As historian Jenna Weissman Joselit points out in her review, however, “By the 1950s, it [Forward] was hardly the only, much less the most influential, voice in town.”Moreover, it had a specific profile, founded as socialist, but sliding closer toward the liberal mainstream throughout the 20th century. Its writing is quoted at length by Adin, but barely contextualized within the shifting fortunes of the paper itself, as if what it had to say about the boys had no relation to its politics.

Indeed, on this point, Joselit’s words echoed throughout my reading: “A greater contextual knowledge of American Jewish history -- and, most especially, of earlier instances of malfeasance -- would also have enhanced the story she unfolds, highlighting the ways in which this gang of four both belonged to and departed from earlier generations of n’er-do-wells.” Connections to the similar 1920s case of Nathan Freudenthal Leopold and Richard Loeb, two young Jews who committed a murder to prove their superior intelligence, is referenced in passing (63) and dismissed, while Jewish organized crime is completely unaddressed. The end result is that the “thrill-kill” gang seems, somehow, and despite passing mention of others’ crimes, to stand alone.

Also worth addressing in this connection is the chapter on Jewish responses, which centers on the notion of Yiddishkeit, and which Adin equates with “religious education” (59). This is a problematic reading, since Yiddishkeit had been promoted as a common Jewish bond largely over and instead of religion; it was promoted by people “united in the belief that religious practice was less critical to Jewish preservation than shared experiences and values, the sense of being one interrelated family concerned with the welfare of fellow Jews wherever they might be. They looked to these common denominators -- which collectively came to be known as Yiddishkeit, or Jewishness -- to unify and preserve Jews, even as the formal practice of religion came more and more to divide them."[1]

The second half of the book’s title is also somewhat misleading. Comics play a vanishingly small part in her story. The connection Adin makes to the comic book scare is tenuous, and the importance she gives the case in the moral panics over juvenile delinquency and comics is inflated. The thrill-kill gang case was primarily used as “proof” of positions already long staked out. Granted, it is clear from the material cited verbatim by Adin that it was a factor in New York’s anti-comics legislation, but it was nonetheless just a spot in the larger picture. As Adin herself notes, all the actors had been invested in the crusade for years, and seem to have latched onto the case only because of its high media profile. The legislation that passed in the wake of the “thrill-kill” case may have had help from recent events, but the story is much longer, and much more complicated.

One notable aspect of Adin’s narrative is the revelation that psychologist Frederic Wertham was an important contributor to the linking of the “thrill-kill” crime to comic books. This is only to be expected, since Wertham, a staunch anti-comics activist and pivotal figure at every step of the comic book scare, was also a highly competent self-promoter. The “thrill-kill” case belongs in any narrative of the comic book scare, but it is in no way the centerpiece. A number of earlier works have ably demonstrated this point already. Adin uses these works to support her own claims,but also misrepresents them as dismissing the “anticomics movement as a bunch of high-brow, sexually repressed elites upset over the popularization of American culture” (xiii).[2] What is missing is a connection to the bigger picture, a clearer explanation of why certain actors latched onto the case (only Wertham gets a sustained introduction in this regard), their interest in banning comics, and the political and personal motivations involved.

In short, while definitely a worthwhile read, the book suffers from a lack of contextualization that would have helped make it a deeper and more lasting contribution to the literature on juvenile delinquency, American Judaism, and comics history.

Martin Lund is a Swedish Research Council International Post-doctoral Fellow at Linnaeus University (Växjö, Sweden) and a Visiting Research Scholar at The Gotham Center for New York City History.

[1] Jonathan Sarna, American Judaism: A New History (:): 166.

[2] The prime source and villain for Adin is David Hajdu and his The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How it Changed America. Adin does deserve credit for pointing out how comics history often presents the comics industry as somehow not foremost a capitalistic venture.