“All of That is What Feminism is to Me”: Building a Multiracial, Working-Class Women’s Organization in 1970s Brooklyn

By Tamar W. Carroll

In 1969, Mobilization for Youth (MFY) social worker Jan Peterson left the Lower East Side for Williamsburg, Brooklyn, heeding a challenge posed by Congress of Racial Equality leader Marshall England: to organize in a white neighborhood. Peterson’s trajectory after MFY captures much of the effervescent rise of social movements in the seventies, as well as the many tensions and contradictions building within the movements themselves and in American politics more broadly. Inspired by the example of the African American civil rights movement and the promise of the War on Poverty, many grassroots activists organized Community Action Programs (CAPs) with the goal of both improving the immediate material circumstances of their members and creating a mechanism for their voices to be heard and taken seriously in policymaking. While the 1970s are often remembered as a decade of racial and ethnic polarization, in many cases CAPs and their successors drew participants together in interracial efforts….[1]

As a community organizer in a racially mixed neighborhood, Peterson worked to mitigate feelings of racial distrust, drawing on the progressive strain of the white ethnic movement and its conviction that people who are “strong in their own ethnicity are better allies.”[2] Consciousness-raising around ethnicity assisted in the formation of partnerships between white ethnic and African American and Latina activists by creating analytic tools for understanding multiple forms of oppression and deepening empathy for those with different identities….

In the first half of the 1970s, Peterson and members of the National Congress of Neighborhood Women, the organization that she founded in Williamsburg/Greenpoint, participated in and drew from the white ethnic and neighborhood movements; in the second half of the decade, they truly developed their own working-class feminist organization, with affiliates in a dozen cities across the United States, ranging from Bayamon, Puerto Rico to San Francisco.[3] By 1976, between 300 and 400 women regularly participated in local NCNW programs.[4] The NCNW’s lightning-quick growth both mirrored the expansion of the feminist movement locally and nationally, and helped drive it. Project Open Doors, the NCNW’s federally funded jobs program, placed hundreds of women in feminist nonprofits across New York City, providing a snapshot of the feminist movement and capturing its variety and vibrancy….

In the fall of 1975, Williamsburg-Greenpoint residents faced plans to eliminate schools, libraries, police stations, fire stations, bus lines, and hospitals. Angry about the planned cuts, as well as about noise and pollution from the expressway and leaking sewers at the derelict Brooklyn Navy Yard, residents conducted a series of dramatic protests.[5] Encouraged by Peterson, Northside residents mobilized a long-term campaign to save their local firehouse, No. 212, which the city planned to close in November 1975 when it reduced its firefighting force by 900.[6] This threat made residents especially fearful for the safety of their homes and families because most housing in the area was old and wood-framed, with buildings connected by common garrets, making them burn quickly.[7] The recent spectacle of large swaths of the South Bronx, as well as neighboring Bedford-Stuyvesant, succumbing to arson made Northside residents anxious that absentee landlords might follow suit in their neighborhood and set fire to their unprofitable properties in order to claim insurance payments.[8]

With the aid of the local firefighters, residents organized an eighteen-month-long civil disobedience campaign designed to keep the firehouse open. On Thanksgiving Day 1975, when fire commissioner John T. O’Hagan sent a crew of twenty-four to remove Engine 212, more than 200 residents occupied the station, holding the engine and the firemen hostage. The next day, after negotiations with O’Hagan, the residents set the firemen free but continued to occupy the firehouse, which they renamed People’s Firehouse No. 1. Polish American Northside grocer Adam Veneski moved into the firehouse with his wife and four children and organized volunteers to continue the occupation around the clock. For the next year and a half, residents decorated the firehouse, took turns sleeping in it, and held communal meals and dances there, turning it into a community center.[9] Every Wednesday night, a local Action Committee met at the firehouse to discuss the impact closing No. 212 would have on the response times of the fire department and strategized about how to get the city to respond. The committee documented the deaths of eight Northside residents in fires following the removal of Engine 212 and began a series of dramatic demonstrations across the city, dumping ashes from the burned-down houses at politicians’ doorsteps, burning political figures in effigy, and blocking traffic on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway during rush hour….[10].

This is the trailer for People's Firehouse #1, a riveting 25 minute-long documentary film by Paul Schneider, released in 1979, that traces the political development of Northside residents as they become involved in community organizing, direct action and civil disobedience to keep their local Firehouse open as large swaths of the neighboring Bedford-Stuyvesant, as well as the South Bronx, succumbed to arson.

Williamsburg-Greenpoint women played key roles in the People’s Firehouse struggle, even donning firemen’s uniforms to march through the neighborhood. Yet, the simultaneous efforts of Peterson and a group of Italian American women from the Conselyea Street Block Association to establish a senior citizen and day care center proved much more controversial, in part because their activism violated Italian American gender norms, which restricted women to taking care of family members within the home. Angie Giglios recalled that before joining Peterson’s group, she “was a home person. I never went anywhere, like I never went to any places to speak in crowds or anything like that.” While women exercised considerable power in this domestic role, they were also presumed to be subordinate to their husbands and brothers on issues outside of the home and were not supposed to engage in public speaking or other leadership activities.[11] Tarantino explained that “at that time, you are the woman; you’re in the house; you stay in the background; you’re not to talk. . . . You just bring up the children.”[12]

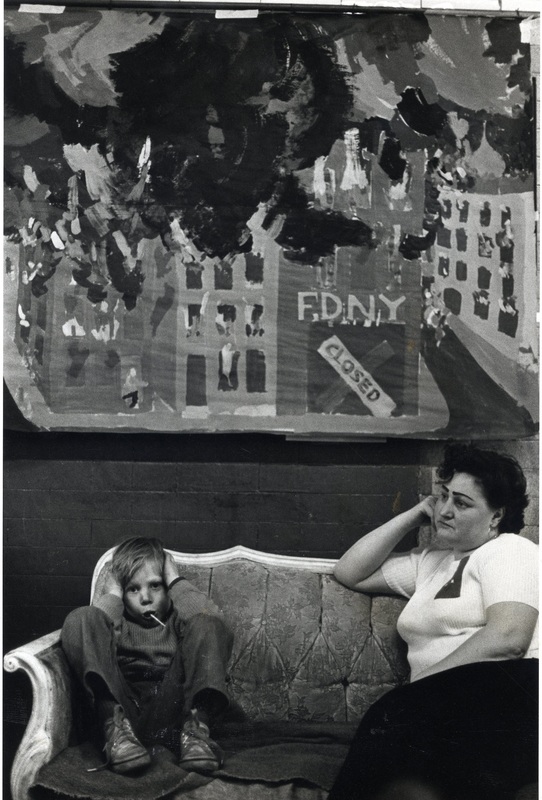

In 1975-76, as New York City's fiscal crisis worsened, the head of of city housing development, Roger Starr, announced a controversial policy of "planned shrinkage": the withdrawal of police and fire stations and the closure of schools, hospitals, and subway stations in poor and non-white areas of the city. Firehouse 212 was slated for closure by the city; beginning on Thanksgiving Day, 1975, Northside residents occupied it for 18 months in a civil disobedience campaign aimed at stopping the cuts. They painted this mural on the Firehouse door.

Photograph by, and courtesy of, Janie Eisenberg.

Residents decorated the firehouse, took turns sleeping in it, and held communal meals and dances there, turning it into a community center. The local action committee documented the deaths of eight residents in fires following the removal of Engine 212, and activists used People's Firehouse as a venue for hearings to bloster the passage of state legislation blocking further layoffs in the New York City police and fire departments. Photograph by, and courtesy of, Janie Eisenberg.

Not only did the Conselyea Street women challenge traditional gender relations, they also violated norms of racial segregation. Opponents charged that the establishment of social services would bring “blacks here, and Hispanics,” and race-baited Peterson and her supporters. Attempting to assert their control over their families and the space of their neighborhood, some white ethnic men responded to the proposed construction violently. Tarantino recalled the threats: “‘You’re going to bust the block and blacks will ruin the neighborhood.’ I mean, they wanted to kill Jan Peterson in Our Lady of Mt. Carmel.”[13] The controversy escalated to the point that the women were receiving phone calls warning them that if they didn’t give up their project, their children would be killed.[14]

While the Conselyea Street women were ultimately successful in establishing the Swinging Sixties Senior Center and Small World Day Care, the sexism and racism of Williamsburg-Greenpoint’s male leaders, as well as the national spread of feminism, made them receptive to the specifically gendered critique of power that Peterson helped them to develop. Soon Peterson drew them into a new and larger women’s organization, using her ties to the white ethnic, neighborhood, and feminist movements…. Picking up on the wildfire spread of second-wave feminism, these working-class activists claimed the women’s movement as their own, inflected by their specific class concerns….

In 1975, Peterson succeeded in obtaining federal grants to employ twenty-five Williamsburg women on the first National Congress of Neighborhood Women (NCNW) staff, as well as in local community organizations.[15] The Brooklyn office Peterson established served not only as the headquarters of the national organization but also as the site of demonstration projects that other chapters could adopt. Emphasizing women’s education as the basis for their empowerment and the betterment of the community, the NCNW created an innovative neighborhood-based college program to answer members’ need for formal credentials to compete in the job market and their desire to become more effective agents of social change. Beginning in September 1975, the NCNW offered tuition-free courses in Williamsburg with a curriculum designed to meet the needs of the organization’s largely middle-aged, homemaking membership in a two-year program. NCNW leaders recruited African American and Latina members of the Cooper Park Tenants’ Association to the program, many of whom welcomed the opportunity to receive college credit. As Christine Noschese, the first director of the program, observed, group education became one of the NCNW’s most effective tools for alliance building between women of different races and classes….[16]

Cooper Park Tenants’ Association leader and NCNW graduate Diane Jackson remembered the college program as the most important site of interracial dialogue: “We had to get over a lot of obstacles. . . . In working with these other women from outside the community [the instructors], we were able to identify what those racial issues were and talk about it…. We began to find out more about each other, found out that we had a lot in common.”[17] The program’s feminist analysis of social institutions, especially of the family, led members to recognize shared needs, including the right to be safe from domestic violence.

In 1976 the NCNW College Program sponsored a “speak-out on wife battering,” with more than 100 people in attendance as women testified to the need for safe places they could go with their children to escape domestic violence. The speak-out led to the founding of a nonprofit organization, the Center for the Elimination of Violence in the Family, and the establishment of the first publicly funded battered women’s shelter in New York State, the Women’s Survival Space, a joint effort between the NCNW and YWCA.[18] Jackson was among the NCNW members who helped to found, and then to staff, the shelter. She recalled the special satisfaction she felt in being able to help other women in a similar position and to collaborate across lines of difference:

Women were prominent participants in the struggle over People's Firehouse; however, it took the leadership of an outside organizer, Jan Peterson, to involve them in explicitly feminist activities. Photograph by, and courtesy of, Janie Eisenberg.

I didn’t feel good about being a battered woman, but I felt good about doing something about my situation. I felt that it was my mission to let other women know that there was help available. My ideal individual goal has been accomplished with the establishment of a battered women’s shelter. . . . All of that is what feminism is to me. It’s sharing, working with each other for the betterment of all women, on issues that cut across ethnic and racial lines. It doesn’t matter whether you’re black, white, whatever. I feel very good about that.[19]

With the founding of the Women’s Survival Space and Project Open Doors, the federally funded jobs program that staffed nonprofits across the city, the NCNW took on a leadership role within New York’s growing feminist movement. At the same time, however, NCNW members also issued class-based critiques of what the media portrayed as “mainstream” and NCNW members saw as middle-class feminism. Continuing to work together across differences of race and class posed ongoing challenges and led the NCNW to develop a leadership-support process to facilitate better communication between allies….

Tamar W. Carroll is Assistant Professor of History and Program Director, Digital Humanities and Social Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology. This is the second excerpt from her new book Mobilizing New York, to be featured on Gotham. The first, discussing MFY's rent strike organizing in the early 1960's, can be read here. A third and final excerpt, on the AIDS activist groups WHAM! and Act Up, will appear soon.

This video features black and white footage filmed by Christine Noschese in the mid- to late 1970s of NCNW speak outs and programs related to the group’s college program and Project Open Doors, an NCNW job training program funded through the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA) which placed unemployed women in 38 feminist non-profits throughout New York City. This selection of excerpts was made by Susana Arellano, Tamar Carroll, and Christine Noschese, with help from Stefani Saintonge and Lars Schumann.

Notes

[1] Annelise Orleck and Lisa Gayle Hazirjian, eds.,The War on Poverty: A New Grassroots History, 1964-1980 (Athens: University of Georgia Press), 2011.

[2] Jan Peterson, interview by Tamar Carroll and Lara Rusch, August 16, 202, transcript of audio recording, New York City Women Community Activists Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Northampton, Mass.

[3] “Affiliates,” Neighborhood Woman, vol. 1, no. 3 (November/December 1977), NCNW Records, Box 29, Folder 5, Sophia Smith Collection.

[4] Enid Nemy, “For Working-Class Women, Own Organization and Goals,” NY Times, January 24, 1976, p. L20.

[5] Interview with Rosalie Wysoboski, NCNW Records, Box 143, Tape 1 Side A. Pollution remained a pressing concerns for Williamsburg residents and led to environmental justice activism in the 1980s and 1990s, documented in Julie Sze, Noxious New York: The Racial Politics of Urban Health and Environmental Justice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 2007.

[6] Ida Susser, Norman Street: Poverty and Politics in an Urban Neighborhood (New York: Oxford University Press), 1982: 162.

[7] Janie Eisenberg, interview by Tamar Carroll, Manhattan, May 31, 2006.

[8] For accounts of the fires in the South Bronx, see Jill Jonnes, South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of an American City (New York: Fordham University Press), 2002; Jonathan Mahler, Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning: 1977, Baseball, and the Battle for the Soul of a City (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), 2005.

[9] Lena Williams, “Brooklyn Drive Pressed to Open Local Firehouse,” NY Times, November 28, 1976; Frank J. Prial, “Protest Is Planned on an Alleged Shift of Rescue Company,” NY Times, January 2, 1977, p. 11; Paul Schneider, dir., People’s Firehouse #1, DVD, 1979; Eisenberg interview.

[10] Schneider, People’s Firehouse #1.

[11] Robert Orsi, The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and Community in Italian Harlem (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 1985: 129–49.

[12] Elizabeth Speranza, Tillie Tarantino, Angie Giglios, and Jan Peterson, group interview by Mary Belenky, February 26, 1992, transcript titled “NCNW,” p. 7, NCNW Records, Box 8, Folder 4.

[13] Tillie Tarantino, quoted in Mary Field Belenky, Lynne A. Bond, and Jacqueline S. Weinstock, A Tradition That Has No Name: Nurturing the Development of People, Families, and Communities (New York: Basic Books), 1997: 212.

[14] Speranza, Tarantino, Giglios, and Peterson, group interview by Belenky, p. 13.

[15] Lindsay Van Gelder, “National Congress of Neighborhood Women: When the Edith Bunkers Unite!” Ms., February 1979, NCNW Records, Box 28, Folder 10. The funds came from the pilot for the Comprehensive Employment Act (CETA). Peterson, interview by Carroll and Rusch, August 16, 2002.

[16] Christine Noschese, telephone interview by Tamar Carroll, March 15, 2006.

[17] Diane Jackson, interview by Martha Ackelsberg, New York, April 28, 2004, tape recording.

[18] Lindsay Van Gelder, “Battered Wives Hit Back at the System,” New York Post, December 2, 1976, NCNW Records, Box 28, Folder 10. The Women’s Survival Space, now part of the Center Against Domestic Violence, is the longest-operating domestic violence emergency shelter in New York.

[19] Diane Jackson, “Diane Jackson,” NCNW Records, Box 75, Folder 24.