A Sow's Ear...

By Benjamin Feldman

“You can’t turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse” goes the popular refrain. I beg to differ, though: sometimes one may.

Browsing among the vast piles of bric-a-brac in a Chelsea flea market right before Hannukah, a tiny leather change purse caught my eye. Sifting through piles of dust-covered junk, golden lettering on the item’s battered side gleamed at me like a nugget in dirt. The Yiddish version of the old song sprang into my head, my grandfather’s shmaltz-coated voice ringing in my ears: Fun a khazerishe ek, makht men nisht keyn shtraymel” “From the tail-end of a pig, one doesn’t make a Hasidic man’s fur-banded holiday headpiece.”

Suddenly I was sure I had beaten the odds. Though designed for small coins and subway tokens, and ostensibly empty, I knew right away that this little sack held lode-bearing ore. Sol. Goldberg’s Cafe and Restaurant 71 Canal Street 2111 ORCHARD glowed from the crinkled skin. This lagniappe, this swag, held a big, fat story. Who was my fellow, this Jewish version of Oscar Delmonico, dreaming success for his little hash house? Likely, his reach exceeded his grasp.

Desperate to know, I rushed downtown to Allen and Canal Streets and found Sol’s building still standing there, now home to Chinese restaurant suppliers and factory lofts with no names on their doors. The scent of secret commerce and bribery filled the air. Nearby loomed a ghost-ridden tower. The florid 1912 shell of Jarmulowsky’s Bank still dominates the corner of Eldridge and Canal. That family fortune started in Hamburg, where in the 1870s patriarch Sender J. sold steerage tickets to multitudes of Sol Goldbergs on credit, and then “safeguarded” their tiny savings from miserable New York sweatshop salaries squirrelled away after paying off their passage debts. Thousands of depositors lost everything at the outbreak of The Great War when the bank suddenly failed. The deceased founder’s two sons had been “jumpers” in Harlem real estate schemes, using hard-earned passbook dollars to speculate, instead of protecting their depositors’ gelt. A near-riot ensued as a mob marched on City Hall, demanding justice and restitution. As I gazed on the majestic facade of the failed institution, all about me drifted vapors of cheap booze on the breaths of disconsolate barflies, drowning the misery at Sol’s bar and brass rail. Then I hurried home with my precious purchase.

Consider the phone number in the purse’s gilt lettering. Why its strange order? I knew the purse was old, but exactly from when? New York telephone exchanges disappeared in the 1960s with the introduction of “all-number” dialing. Memorialized by novels like BUtterfield 8, two letters and a digit corresponding to the third letter of the old exchange names began all connections after 1920. But on this leather trinket, as was the custom before 1921, four digits precede the exchange. A determined push through the fog of Manhattan telephone and borough address directories cleared the glass. Sol Goldberg was a liquor dealer and saloon operator down on Canal Street, handing out change purses while striving to stay alive after Prohibition’s 1919 start.

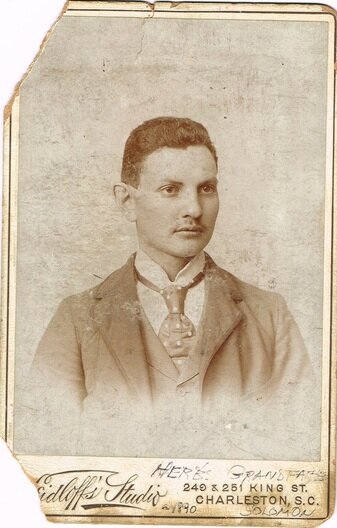

A visit to the New York County Clerk’s Office followed my phone book leaf-through. I found another listing in a reverse directory for 1920 at 71 Canal next to Sol Goldberg and his cafe. The “Eagle Non-Intoxicating Wine Company” fit right in. A quick visit to the New York County Clerk’s Office confirmed the formation of this majestic-sounding enterprise by Sol and his elder son Herbert. Hope and khutspeh survived, even after Carrie Nation won the brawl. But business was lousy or perhaps it needed a quieter address. By 1921, Sol and Herb disappeared from Canal Street without a trace.

Solomon Goldberg emigrated from Lithuania (called Russia in the census documentation) in 1892 in his late teens, and then left New York to stay with relatives in Virginia where he found work in a sheriff’s office. By 1898 he had returned to New York, and lived with his parents Wolff and Mary Goldberg at 149 Ludlow Street.

Engaged to Rosa Fridlander, Sol married his lantsman in 1898 in a non-religious ceremony performed by alderman James Gaffney at 232 East 22nd Street in front of two gentile witnesses. Sol leased one of his first saloons at 17 Ludlow by 1902, a modest structure on the west side of Ludlow, just north of Canal. Though the ethnicity of the building and surrounding blocks is overwhelmingly Chinese today, 17 Ludlow, its back house, and the immediate environs bear a remarkable resemblance to how they looked in 1902. Overcrowded apartments and small businesses dominate the neighboring tenements. Steam vents still pour from upper floor windows. Chinese signs are plastered on doorways. Mandarin or Yiddish, it’s all the same: struggling to survive remains the game.

With the backing of the omnipresent Lion Brewing Company, Sol signed a formal lease for 17 Ludlow’s northerly store and the four dwelling rooms above, for a term of five years, starting March 5, 1903. The rent was pegged at $75 a month, with Sol giving a promissory note of $103 for security, while also agreeing to pay charges for “Croton Water.”

In a move probably calculated to frustrate future creditors, Sol assigned his Ludlow lease to his wife 13 months later, setting a pattern for his post-Prohibition life. On the Lower East Side or deep inside Russia, A Jewish boy stayed ahead of the law. The couple apparently did well enough to sell the Ludlow Street saloon in 1908 right after renewing the lease, and moved to a larger tenement at 236 East Broadway when Sol began his liquor business at 71 Canal Street.

Trow’s Directory also lists a Sol Goldberg in East Harlem as a bottler in 1909-10. The alcohol trade may have been an up and down one (or the 236 East Broadway apartment too small for an ever-growing family), because by 1911, Sol and his brood moved to 97 East Broadway where they lived with Rosa’s unmarried milliner sisters Gertrude and Mollie. #97 though dilapidated inside, still stands on a block that was permanently cast into shadow by the construction of the Manhattan Bridge and its 1909 opening.

Several children were born to Sol and Rosa: Herbert in 1899, George Milton in 1904 and Helen in 1908. As Sol’s liquor and saloon business prospered at 71 Canal, the family moved from 97 East Broadway to #259, a slightly newer structure, and then left the squalid and overcrowded East Side, moving first to a tenement on Rockaway Avenue in Brownsville and then to a sizable, newly-built attached brick house on Martense Court in central Flatbush. With the advent of the First World War and the August 1918 amendment to the prior year’s Selective Service Act, all males between 18 and 45 years of age were required to register. One year under the limit, and clearly a poor choice for a return trip to Europe, Sol, a naturalized US citizen, did his duty anyway, but wasn’t called. But even with the Versailles treaty inked and official, a live shell still landed, smack in his face.

The Volstead Act of 1919 struck a violent blow to Sol and his family as well as tens of thousands of families, Jewish and gentile alike. All over America, alcohol went underground, and tens of thousands of formerly legal, respectable jobs disappeared. In America, Sol had followed a time-honored Jewish trade. Though barred from many professions in Eastern Europe, Jews had been tavern owners there at least since the 18th century, filling a strange function in Catholic-dominated societies where the “sin” of facilitating inebriation was pawned off on the unclean killers of Christ. The liquor trade also supported large-scale agriculture to produce the basic grains and potatoes that fed the distilleries and provided significant tax revenues to the state. The gradual tightening of Polish governmental restrictions on Jewish tavern keepers grew through the early 19th century, though, and they were forced into all sorts of extra-legal gymnastics to avoid starvation. With the closing of his hopeful “cafe and restaurant” at 71 Canal, Sol Goldberg would trod a well-worn path.

My research trail went very cold after 1920, Sol’s name disappears from directories. His wife, who owned title to 1 Martense Court, sold the house in 1922, and it is unclear where the couple and their young adult and teenage children moved next. By 1930 they had landed at 80 Winthrop Street, not far from their Martense Court home in halcyon days. Listed as a “restaurant owner” on official documents until his dying day, I couldn’t first figure Sol’s sudden disappearance. What was he up to after the Volstead hammer blows rained down? Did Sol open a candy store, a luncheonette or a deli? None of the post-1920 Manhattan or Brooklyn phone books yielded a clue, and the trail of possible living relatives to question went very cold. After months of frustration and useless detours, I hired an expert and uncovered the truth.

In one day’s work, a professional genealogist unlocked the secret, linking together a 1930 birth announcement in the New York Times together with a current Nevada phone number for a possible hit. Sol’s estate administration papers, filed in Kings County Surrogate’s Court at his death in 1943, list a widow and three children, among them one George Milton Gardner, who had changed his last name. I had already found George, back when his last name was Goldberg, living on East 21st in Manhattan when he married May Klein in a religious ceremony in 1925. On March 9, 1930, Mr. and Mrs. “Rube” Goldberg (nee May Klein) announced the birth on February 21st of that year of a son, Robert Allen. It was too close a coincidence. I’d found my man.

My voice trembled a bit as Allen Gardner answered the call. “How did you get my number?” an old man said. I tried to hide my own trepidation. Another person was listed at the Reno address, a Dar Es Salaam. Perhaps an Al Qaeda terrorist cell? After a bit, Allen warmed to my interest, being still careful about what he disclosed. 81 years old and retired from a distinguished career as an animal behaviorist, Allen and his late wife had taught the chimp Washoe to use sign language in 1969. I easily recognized the famous chimp’s name. Talk about swag! Then we cut to the chase. When Allen was a baby, his parents would take him for rides in their car, traveling Brooklyn’s leafy streets. The police never stopped a young couple with a baby. Even with cases of hooch on board. Milton and May did the deliveries. Sol handled the wholesalers. The family scraped by. Arnold “The Brain” Rothstein controlled the flow of juice to Sol’s customers until Rothstein was rubbed out at the Park Central Hotel in 1928 and members of his minyan, Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky, took control.

The sow’s ear started morphing as I talked to Allen longer. The shape of that fancy Jewish headgear began to appear. As with any raiment, these bonnets come in gradations. I ended up with the finest in the store. “Perhaps you heard of my late brother Herb?” the old man said. “He was a playwright, kinda well known.” “Herb Gardner?” I shot back. “The name is familiar.” “His last play was Conversations with My Father, not so very long ago.”

My spine tingled like icicles on my bare neck in winter. I’d loved the show on Broadway in ’92. Judd Hirsch played the lead roll, Eddie Goldberg. The set was a dingy bar on Canal Street, New York. As we talked more, my excitement only grew. Herb Gardner also authored A Thousand Clowns, I’m Not Rappaport, Who is Harry Kellerman and Why is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me?, and The Goodbye People. What a piece of true dumb luck. Blanks had been missing. The play, albeit fiction, fleshed a lot out. I nabbed it forthwith from the library stacks, eating the words off the pages, scarfing down the beak and the bones.

Sadness informs and infuses Conversations. In it Sol Goldberg is portrayed as an upright man whose insistence after Prohibition began on selling only legal near-beer and his refusal to deal with bootleggers got him murdered in Cortlandt Alley. The alley seems dangerous, perhaps moreso today: It runs south of Canal and west of Lafayette Streets, hard by the ancient loft buildings where upstairs warrens of dark storehouses harbor soft goods counterfeiters. Gullible tourists are robbed blind there now every day of the week.

Eddie Goldberg, modeled after Allen and Herb’s father George Milton Goldberg (Gardner), is a tough-talking cynical barkeep and irascible father, slinging drinks in a low-end dive that he keeps remodeling and redecorating to try and attract a better clientele than the alkies and bums who drift in from the streets near the Tombs and the court houses. 8:00 a.m. each day finds a line at the door. The play, in truth, is a confabulation. Sol Goldberg played along with Rothstein and more. The year after Prohibition ended in 1933, Sol’s wife, son Herbert and a fellow named Israel Civin from Borough Park, formed a corporation and leased a bar at 258 Canal Street, where McDonalds sits today. Strangely, Sol’s name does not appear on the corporate formation documents, though the following year, trade name documents were filed in New York with Sol and without Mr. Civin, registering the trade name “Silver-Gate Restaurant” at 258 Canal Street, with Sol’s younger son, George Milton Gardner (f/k/a Goldberg!) listed as an owner also.

The Silver Gate Bar and Grill operated there until Sol’s death from cardiac failure and pulmonary edema on August 8, 1943, Dr. Bertha Kalish pronounced Sol dead at Jewish Hospital in Brooklyn where he had lain for 12 days prior. Manhattan’s Riverside Funeral Chapel handled the arrangements when Sol was buried at Beth David Cemetery in Elmont, Long Island, 11 days later. Why the delay is an open book. Rosa, his widow, did not last long. After suffering at their home at 57 Lincoln Road for six months from hyper-nephroma and hypertension under the care of her neighbor, Dr. Gustave Bers, Rosa passed away on May 2, 1944 and was buried along Sol the next day. Her son, George Milton, who had altered his surname to Gardner at least 20 months before, must have had a change of heart or felt guilty as the molokh hamoves, the angel of death, came knocking again at the family door. On Rosa’s death certificate, he is listed as informant. George Milton Goldberg resumed his boyhood role.

Sometimes success will skip generations. Sol’s swift-footed career didn’t end so well. The Silver Gate Bar was sold by his widow and two sons in 1945. His estate was probated with almost no value attached to his assets. Business at the Silver Gate must not have supported three households well. At Sol’s death he and Rosa were still renting their home. At least the couple tried to do the sewing. For a Jew, pig skin is tough to cut and stitch. Though the end result of Sol Goldberg’s Cafe was certainly no fancy headpiece, it still outshines many, its lettering still aglow.

Benjamin Feldman has lived and worked in New York City since 1969. His essays about New York and Yiddish culture have appeared on-line in The New Partisan Review, Ducts literary magazine, and in several earlier editions of The Gotham History Blotter. Much of his work can be read on his website, The New York Wanderer. His books include Butchery on Bond Street- Sexual Politics and The Burdell-Cunningham Case in Antebellum New York and Call Me Daddy – Babes and Bathos in Edward West Browning’s Jazz Age New York.