A (Female) Walker in the City: An interview with Lauren Elkin

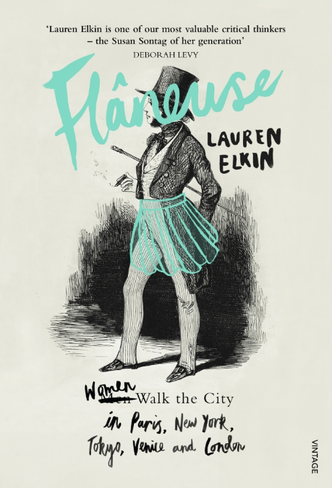

Today on Gotham, editor Nick Juravich speaks with Lauren Elkin, about her recent book Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London, selected as a Book of the Year by the Financial Times, Guardian, New Statesman, Observer, The Millions and Emerald Street, and shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay.

The first and most obvious question we ask is always, "How did you come to write this?" You discuss this a bit in the book, of course, but was there a particular moment or book or event that helped you decide, "This is a book I want to write"?

To answer this I need a little Walter Benjamin, if I may. In one of his best-known essays, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Benjamin writes about the “aura” that hangs about a work of art, that no matter how many times we see it in photographs, means we still defer to the aesthetic presence of the original. I’d venture to say that when it comes to reading and writing about cities, there’s a body of work that has this “aura” about it — Baudelaire, Benjamin himself, Breton, De Quincey. We have our little canon of writer-walkers, and we love them dearly, and fetishize them wantonly; we quote them over and over and they retain the same power, the same authority to express what it means to live, walk, and wander in a city. But they're all men; the cities they describe are those cities as experienced by men. Janet Wolff talks about this in her important article “The Invisible Flâneuse,” which was a touchstone to me when I was doing the initial research.

Again and again when I was writing this book I asked myself, how has Paris, or Tokyo, or New York, been seen differently by women? Whose are the voices? Where can I hear them? And how can I understand my own city walking within this alternative tradition? I was able to write about a handful of female writer-walkers, to take back the city a little bit, but it was my hope throughout that it would be clear to readers that my book was just a gesture at bringing attention to this alternative urban history, and that they should feel free to bring their own voices, their own readings, to the conversation, imbuing a female vision of the city with its own aura of If you love cities, you must read this.

As a bunch of historians, we're keen on process questions. How did you go about researching the book? Were the writings and stories of your flâneuses already familiar to you? Did you find anything along the way that surprised you? To be New York exceptionalists, as is our wont, was there a particular New York City fact or story or history that you found in the process that stands out?

Some were familiar to me; I’d written my PhD on Jean Rhys and Virginia Woolf, so I knew the texts and the criticism. Others, like Martha Gellhorn, I knew of but didn’t know until I started reading their work how they would work as flâneuses. I read pretty widely, but something had to click between the figure and my own walking in cities; one of the constraints of the book was that I was only writing about cities where I myself had spent a substantial amount of time, and another was that their story and my story had to be mutually amplifying, which excluded for instance Nella Larsen, who was in the original proposal. Once it was clear that I was writing some kind of memoir of my life in cities, it no longer worked to be writing about “Passing,” because it was pretty lame to then relate that back to my own life; I wasn’t going to juxtapose her wonderful novel of complex race relations during the Harlem Renaissance with my own experiences trying to, I dunno, “pass” for French. I’ve thought ever since that that was one of the limitations of the project as it turned out; having to hew to a memoir-based narrative arc, instead of an argument-based one (which was the original idea for the book, but my editors wanted the memoir material to be there) meant I couldn’t cast as wide a net in terms of the flâneuses I included.

But when it worked it worked; in each chapter I paired a flâneuse with some moment I was living through personally, and once I found the correspondences I could set the chapter in the key of some thematic idea that functioned like a mood or key; so the Tokyo chapter is called “Inside"; the Varda chapter is about the concept of the neighborhood and the idea of settling; the Calle chapter is called “Obedience.” I knew about Sophie Calle’s Venice project, in which she followed a random man around the streets of Paris and then from Paris to Venice, but as I started reading her diary notes from that trip, and her writings about her relationship with her father, the theme of obeying and following kept jumping out at me, and resonated with the kind of disobedient obedience I was practicing in my life at that time: disobediently writing a novel instead of my PhD dissertation, while also trying to insert myself into a cultural framework that preexisted me and that might give my life meaning (in my case, trying to become French, or “more” Jewish).

As far as New York itself goes: I would say that writing this book gave me a newfound fondness for the edgelands of New York City. The final chapter gives a kind of psychogeographic account of the ride into Penn Station on the Long Island Rail Road, a journey I used to find tedious in the extreme, but once I really started looking at the landscape (for lack of a better word) and thinking about how it was put together, I realized how much a part of me it is. New York has changed so much since I lived there, and I often feel kind of alienated from it, like it belongs more to all these outsiders from other places than to me, who grew up in its orbit and came of age there. But it’s not true; there’s a relationship to space we acquire over time that no one can challenge or take away from us.

The book is many things, as both reviewers and you yourself describe it: cultural history, literary criticism, memoir, polemic, etc. As history (since that's our bailiwick), what kind of a contribution did you want to make? How does the history of the flâneuse help us rethink urban history more broadly?

This is something I’d love to hear from more historians about. As a literary scholar, our primary sources are the texts we work with, as well as whatever other material we can get our hands on. That’s not too challenging when you work on people like Woolf or Rhys; you just have to be able to travel to wherever the archive is held. So as long as I was working on pretty celebrated writers or artists, the material was there. But where I really wanted to be able to develop the book, but lacked the time or the historian’s savvy to be able to do it, is when it comes to ordinary women (that is, those who were not celebrated authors or artists) living and walking in cities. I’d love to know what kind of material there might be, for instance, to see what everyday Parisiennes thought about walking in their modernizing city, at the time when Baudelaire became the voice for walking in a changing Paris.

But more to your point, I think attending to a female perspective on the city allows us to understand the ways in which cities have been and remain today created by men, with a specific idea about the kind of man who uses them. They are not, on the whole, designed for women, children, people with disabilities, minorities, the working class, or the queer community. Looking at the history of the flâneuse opens up a vantage point on our cities that is non-hegemonic; it helps us understand how certain values are built into their very fabric, and enables us to question how we might rethink what a city can be going forward.

New York City features, in your own telling, as a hometown but also as a place "where life is inflected with the future tense." What does that mean for walking in the city? How does New York City feature among the walking cities of the world?

Everyone in New York is in such a hurry, their bodies tensed into forward slashes as they try to get where they’re going. I’m guilty of this as well! We’ve subjected our entire physiognomy to the dictates of the clock. Gotta be here, gotta be there, get outta my way, I’ve got shit to do! I think one of the most subversive aspects of the flâneur, or the flâneuse, or the idler/psychogeographer/whatever you want to call it, is to throw the clock away. It’s the ultimate rejection of capitalism, to opt out of the time is money equation, and that’s what the flâneur or flâneuse does. In New York, one of the business capitals of the world, I think this has even more resonance.

New York, for me, is one of the best walking cities in the world, second only to Paris. I love even walking in Midtown, one of the more soulless parts of the city, because there’s so much happening, so many people to watch, so many small businesses and sketchy businesses toiling away idiosyncratically, watching the way people negotiate traffic, and each other — but then there’s also so much to be said for hitting the sidewalks in the outer boroughs, getting a broader view of how people live, how the city’s put together, what’s happened there, what traces the past has left.

I’m aware there’s a potential tension between the first part of what I’ve said, and the second part. The flâneur or flâneuse stands apart and watches “everyone else” going about their business, as if the city needs people who work and people who can take time out from work. But taking some time out to watch the world is not a privilege afforded only to the very few; it’s a choice we can all make to stop and think about how it’s all put together, and what our role in it might be. Most everyone’s got at least a five minute cigarette break to stop and watch the world go by; that’s one of the things Jane Jacobs loved the most about New York City, that there are always eyes on the sidewalk. They’re not the most privileged eyes either.

An obvious one: Do you have a favorite walk in New York City, either a path you've taken multiple times or a memory of a particular stroll? For that matter, who is your favorite of the New York City flâneuses you chronicle?

I absolutely love walking around Columbia on the Upper West Side; there’s no one route I prefer, but any winding route that takes me past St. John the Divine, into the Hungarian Pastry Shop, into Book Culture (which was called Labyrinth when I lived there), down West End Avenue past all the doormen buildings with their awnings, into Riverside Park…

My favorite NYC flâneuse is someone I didn’t have space to write about in the book: Maeve Brennan. She was an Irish immigrant to the city and wrote a million wonderful little pieces about daily life there for the New Yorker under the nom de plume “The Long-Winded Lady.” I love her wry wit and the unromantic way she recognizes the cultish way people live in New York, a city that she loved but called “a capsized city — half-capsized, with the inhabitants hanging on, most of them still able to laugh as they cling to the island that is their life’s predicament.”

And finally, since the book has been out for a year (congrats as well on the various mentions and lists!), does anything stand out from the way it has been received? Did writing this book uncover any new topics or cities you want to turn to next?

Thank you! Honestly it just makes me want to keep walking in the cities I spend the most time in, Paris, New York, and London, to keep venturing outward — there’s a great blog they’ve started in Paris called Enlarge Your Paris which tries to inspire Parisians to head out beyond the périphériqueinto the banlieues. I’m as guilty as the next person of being pretty provincial in my adopted city, staying mostly within the northeast, where I live, and rarely venturing further afield. There’s so much to see in my own backyard — I think that’s where you’ll be able to find me, for the time being.