Jerri Sherman

Stitching Stories: Jerri Sherman

Jerri's parents

Jerri at age seven

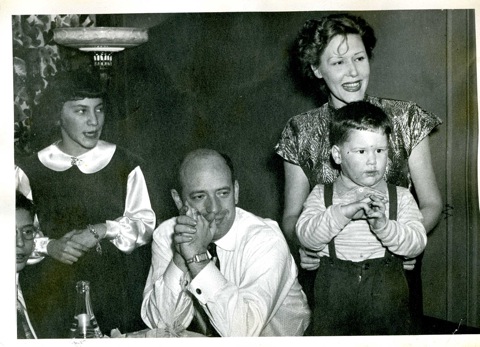

Jerri on the Uncle Miltie Show

Charlie Lowe Dance Studio

My father, Jack Sherman, was a big-time New York bookmaker who made his headquarters in the New Yorker Hotel and handled the Garment Center. His “legitimate” business was called Sherman Auto Corporation, despite the fact that he never learned to drive. He employed his three brothers, Tony, Joe, and Benny in the family business. In his book “Underworld”, Don DeLillo mentions the enterprise, confirming by letter, that, indeed, his uncle had been employed as a “runner” for the Sherman brothers. Later someone explained to me that my father had Mafia ties otherwise he could not have operated freely for so many years. Growing up, my sister, Marian and I had no idea of any of this.

When I was four years old, my parents moved from Brooklyn to 110 Riverside Drive on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, the Jewish Gold Coast. Babe Ruth and his wife lived in the building and on several occasions I saw the uniformed elevator men physically carry the two of them to their apartment after a night of partying. The Babe always wore his famous camelhair coat.

I was a child performer who danced on the Uncle Don Show and did a solo song and tap dance, in a clown costume, on the Uncle Miltie TV show at its height of popularity, nearing toppling the scenery on my entrance as I forgot to duck to accommodate my tall, pointy hat. As a young teenager, I twice passed the audition to be a Rockette but didn’t make it past the first rehearsal. The June Taylor Dance Company asked me to join its national tour, but my mother felt I was too young. After a minor ski injury, I decided against a dance career.

My father’s drinking problem together with a City Commission investigating bookmaking resulted in the arrest of several of his top men causing a shutdown of the business and a complete reversal of our financial situation. Somehow going to college was never an option when I graduated high school at fifteen. At age 16, thinking it a glamorous career to replace my loss of show business, I became a garment center showroom model. It was not a place for an inexperienced young girl, but it represented my entrée into a world that became my home for the next forty-two years.

“The less you wore, the higher the pay scale”

Any girl who wanted to be a model in the garment industry had to go through “Model Service”. That agency placed all the girls for a placement fee of one week’s salary. First you had to choose your category. What were you interested in modeling…dresses, coats/suits, evening gowns, bathing suits, lingerie? The less you wore, the higher the pay scale. I chose coats/suits. Next you filled out a 4 X 6 card on which you listed your height, weight, and dimensions…bust, waist, and hips. It was a one-woman office. For all the times I used it over the years, there sat this same woman. A stern demeanor covered up a relatively kind person, once she got to know you. I don’t remember her ever standing up.

Back in the late 1950s, not all offices had air conditioning. After many temporary jobs, I worked for Capri Juniors, a popular coat/suit company, owned by Isidor Ohringer (the old man) and his two sons. Only the showroom where the buyers sat had A/C. Remember the garment industry works backwards. It showed winter styles in the summer. The moment you left the showroom, the temperature soared into the 80s-90s. All models wore the same uniform; a tight fitting, short little black crepe dress, the “model’s slip.” It had to fit under the samples. And under the “model’s slip” we all wore a “Playtex” long girdle, from waist to mid thigh. For many years made of 100% rubber, Playtex finally added a thin cotton lining to make it bearable. Most of the time I spent in the “back” (the factory), helping to pack coats when we were busy. Boy, did I sweat.

Jerri at age eleven

The head of our shipping department, a department of one, was “Driggs”, a wonderful, kind, old African-American man. We loved each other. I never saw him sober. He always stank from alcohol. But he turned up every day. It took old man Ohringer a year to remember my name. The “dummy” model only wore the clothes and was not expected to have any brains. That changed in my four years with the company. My responsibilities increased. Allowed to make copies, I would jiggle the paper in a tray of copy fluid, push a lever, squeegee two sheets together, pull them apart, then throw one out. Another more important task was stamping hundreds of postcards, announcing the show dates for our three road salesmen, using the Addressograph Machine. This took a solid three hours, twice a year, resulting in my hands and arms being covered in ink. It became clear I had to move on.

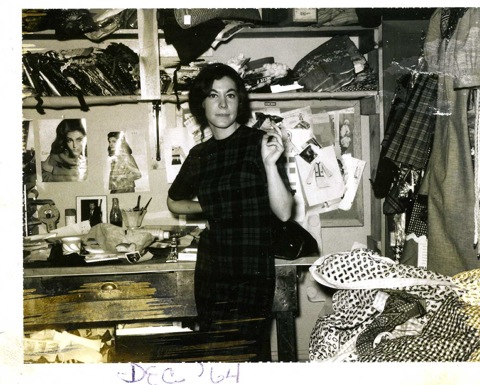

“Just don’t make it a quilted ski parka”

I went to secretarial school to learn shorthand and typing. It didn’t quite take. In 1963 one of my girlfriends, who bought junior sportswear for a group of stores, recommended me for a sales position with one of her suppliers. The company, Antics/MadMax was on a wildly successful selling streak producing inexpensive quilted ski parkas for teenagers. They couldn’t supply them fast enough. A seven AM breakfast was the only time the two owners, Dave Binder and Phil Cantor could interview me. Over bagels I got the job…to start immediately, of course…which I did, of course.

Here my life took a really interesting turn. Now in my mid twenties, Dave and Phil introduced me to Joan Sachs, an eighteen year old recent graduate of Parsons School of Design. Next to their long cutting tables in a basement, they put up a couple of partitions, making a small “studio” for Joan and me. With absolutely no direction or guidance, they left us alone to create. Joan would design it and I would go out and sell it. What? Who knew what; “just don’t make it a quilted ski parka.” Joan had never had a job and my only selling experience entailed turning around and showing the buyer the back of my garment. I wouldn’t be writing this if nothing interesting happened. But something did. From some part of her very talented brain, basically working from scraps, Joan came up with three or four adorable, funny, little dresses for teen girls. They came to be called “shifts”. Now my turn came. I went out to sell styles that didn’t even have a company name. I threw them over my arm and as a formerly rich kid; I went to the Fifth Avenue stores. I don’t know how I did it, but I got to the buyers at Saks, Bonwit-Teller, and others. Now we needed a name. Tossing ideas around the office, someone came up with “Huk-A-Poo”. It fit the humor of the styles and it stuck.

The Saks buyer went nuts for them. She immediately started planning ads and windows. Dave and Phil were astonished. Another time, I burst into a business meeting of the big hit TV show, Hullabaloo, dancing around the room, wearing a fabulous black and white checkerboard Huk-A-Poo shift. The very next week all the Hullabaloo dancers wore it on the show.

Unexpectedly disaster struck. One day all US teenagers woke up and decided never to buy another quilted parka. It ended that quickly. In 1965 Antics/Madmax went bankrupt taking with it the fledgling Huk-A-Poo. Huk never meant to be profitable, couldn’t stand on its own. Dave and Phil had made their money but Joan and I were on the street looking for jobs. Luckily, I still lived at home.

“If you can bring it out at a cheap price, there is no limit to what we can sell”

Fast forward. Now an experienced salesperson, and working for two or three years for a more stable, less exciting junior sportswear company, Dave Binder approached me to join his new company, Pranx. Being a little gun shy, he kept upping the offer. I would receive a good salary, ample time for my adventure travels, and extra time at lunch, twice a week, to see my analyst. I couldn’t refuse. It started out a standard selling job until one day two knitwear designers came to show us their small collection of sweaters. Our eyes popped. They were fabulous! Quickly, Dave told me to run and show them to my friend the Macy’s knitwear buyer. She wrote a $30,000 order on the spot. Unheard of. Now he had to figure out where and how to get them made. Dave still owned the Huk-A-Poo name and brought it out of mothballs for the sweater collection. That was the start of what I call Huk-A-Poo 2. While the sweaters put it on the map, it is the printed nylon shirt that sent it to the moon. It became one of the hottest junior sportswear companies in the 1970s.

How the nylon printed shirt came to Huk-A-Poo is another extraordinary story. The junior sportswear buyer from a major New York store brought Dave a printed nylon shirt retailing for close to $30, saying he couldn’t keep it in stock. He pleaded, “If you can bring it out at a cheap price, there is no limit to what we can sell.” Dave flew immediately to the Orient to arrange production and determined the magic retail price to be $11. From the first shipment we delivered two dozen shirts to Famous Barr in St. Louis for weekend selling. Jim Prager, the buyer called me at 8:30 AM Monday morning to say they flew out by Saturday noon, “send more”. I ran into Dave’s office and shouted, “Hock the family…make nylon shirts.”

Traditionally, the young junior sportswear customer is very fickle. She falls in love and falls out of love very quickly. It didn’t happen here. What makes this story so special is that the nylon printed shirt remained HOT for years, ultimately selling in the millions under the Huk-A-Poo name.

“In those days women didn’t go on the road lugging samples”

In the mid 1970s, Huk-A-Poo contributed so much volume to Macy’s that Ed Finkelstein, the president, personally invited me to sit next to him at the Thanksgiving Day Parade. That’s success! Extraordinary retailing personalities came out of the junior sportswear business in the 1970s. Les Wexner, who later founded The Limited Stores, was just the buyer at his parent’s clothing shop near the campus of Ohio State in Columbus when I flew there to sell him Huk-A-Poo shirts. In California, I remember schlepping my big flowered sample case on wheels up the stairs to the buyer’s office on the second floor to sell Huk-A-Poo shirts to The Gap, the first piece of non-Levi merchandise the store ever bought. In that instance I had an appointment with the buyer, but many times I didn’t. In which ever city I, unexpectedly, turned up, what buyer would refuse to see a young woman struggling with a big sample case on wheels decorated with colorful posies? Nobody! I got in to see everyone and they all bought.

There are so many fabulous stories. When the quota on nylon shirts ran out, Dave had bottoms basted on in HK and brought them in as body suits. He arranged a room where senior citizens removed the threads and, voila, shirts emerged. Another time, on our accountant’s advice, using various pens and multi colored pencils, I sat up an entire night rigging my previous year’s calendar before a tax audit.

The US Government subpoenaed me to appear before a committee on price fixing. Of course we did, but I refused to testify. With my family background I was scared to death. Dave denied guilt but agreed to discontinue certain practices.

On a much higher note, Huk-A-Poo started a baseball team, challenging Macy executives. Maybe we let them win. And in 1978, I arranged for the Metropolitan Museum of Art to accept Huk-A-Poo into its Costume Institute, the first contemporary clothing to be admitted.

Dave Binder, a true entrepreneur, an intellectual, and a family man, respected women’s abilities and paid them accordingly. As his number two person, I earned six figures when men did not. In those days women didn’t go on the road lugging samples. He gave me the opportunity to stretch my wings and try anything. We worked together for almost twenty years when again the time had come for me to move on. I started my own “Jerri Sherman Ltd” label in 1981. My business lasted for 15 successful years. I didn’t wind up in the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute but I did turn up in Barbra Streisand’s closet. I look forward to writing that remarkable story.

See Huk-A-Poo designs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute